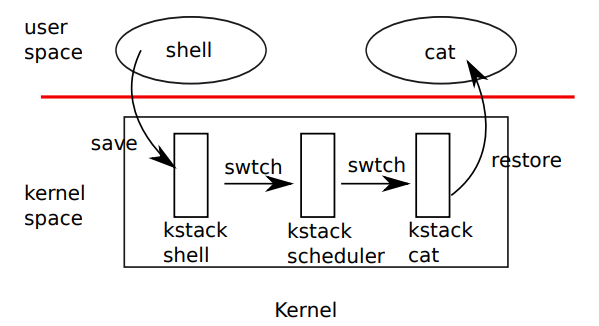

Context scheduling:

outline of the context scheduling

xv6 uses timer interrupt to implement time-sharing of the CPU.

timer interrupt handler calls yield() to yield the CPU to other process.

trap.c

105 if(myproc() && myproc()->state == RUNNING &&

106 tf->trapno == T_IRQ0+IRQ_TIMER)

107 yield();yield() first acquires the ptable lock and calls sched().

385 void

386 yield(void)

387 {

388 acquire(&ptable.lock); //DOC: yieldlock

389 myproc()->state = RUNNABLE;

390 sched();

391 release(&ptable.lock);

392 }

sched() double checks the lock and calls swtch() to store the context of the current process and switch to the scheduler context.

It returns not to sched but to scheduler, and its stack pointer points at the current CPU’s scheduler stack.

This is possible because that scheduler context had been saved by scheduler’s call to swtch and ret instruction in swtch.S assume that the topmost stack -which is saved as scheduler stack- %eip and continues.

proc.c

365 void

366 sched(void)

367 {

368 int intena;

369 struct proc *p = myproc();

370

371 if(!holding(&ptable.lock))

372 panic("sched ptable.lock");

373 if(mycpu()->ncli != 1)

374 panic("sched locks"); //double checks if it holds the ptable lock

375 if(p->state == RUNNING)

376 panic("sched running");

377 if(readeflags()&FL_IF)

378 panic("sched interruptible");

379 intena = mycpu()->intena;

380 swtch(&p->context, mycpu()->scheduler);

381 mycpu()->intena = intena;

382 }swtch() starts by copying its arguments from the stack to caller-saved register %eax and %edx.

Then creating a context structure on the stack by pushing the current callee-saved register.

swtch.S

9 .globl swtch

10 swtch:

11 movl 4(%esp), %eax

12 movl 8(%esp), %edx

13

14 # Save old callee-saved registers

15 pushl %ebp

16 pushl %ebx

17 pushl %esi

18 pushl %edi

19

20 # Switch stacks

21 movl %esp, (%eax)

22 movl %edx, %esp

23

24 # Load new callee-saved registers

25 popl %edi

26 popl %esi

27 popl %ebx

28 popl %ebp

29 ret #ret assume the top-most stack variable is %eip

after swtch() returns to scheduler(), scheduler() continutes to find a runnable process and cycle repeats.

322 void

323 scheduler(void)

324 {

325 struct proc *p;

326 struct cpu *c = mycpu();

327 c->proc = 0;

328

329 for(;;){

330 // Enable interrupts on this processor.

331 sti();

332

333 // Loop over process table looking for process to run.

334 acquire(&ptable.lock);

335 for(p = ptable.proc; p < &ptable.proc[NPROC]; p++){

336 if(p->state != RUNNABLE)

337 continue;

338

339 // Switch to chosen process. It is the process's job

340 // to release ptable.lock and then reacquire it

341 // before jumping back to us.

342 c->proc = p;

343 switchuvm(p);

344 p->state = RUNNING;

345

346 swtch(&(c->scheduler), p->context);

347 switchkvm();

348

349 // Process is done running for now.

350 // It should have changed its p->state before coming back.

351 c->proc = 0;

352 }

353 release(&ptable.lock);

354

355 }

356 }

Sleep and Wakeup

In common Producer/Consumer case, sometimes, you don't need to waste your CPU busy waiting by polling repeatedly for rare produce event.

It may be much more efficient to yield the CPU while waiting.

The pair of calls, Sleep and Wakeup exist. These method is called "sequence coordination" or "conditional synchronization" method.

Correct version of sleep/wakeup method applied example code:

acquiring and releasing lock are needed to protect code from the "lost-wakeup" deadlock.

also, when sleeping the lock must be released, otherwise sender will block forever waiting for the lock.

400 struct q {

401 struct spinlock lock;

402 void *ptr;

403 };

404

405 void*

406 send(struct q *q, void *p)

407 {

408 acquire(&q->lock);

409 while(q->ptr != 0)

410 ;

411 q->ptr = p;

412 wakeup(q);

413 release(&q->lock);

414 }

415

416 void*

417 recv(struct q *q)

418 {

419 void *p;

420

421 acquire(&q->lock);

422 while((p = q->ptr) == 0)

423 sleep(q, &q->lock); //releasing spinlock

424 q->ptr = 0;

425 release(&q->lock);

426 return p;

427 }In sleep, Sleep holds one of sleep’s lock or ptable.lock at all times, so a wakeup cannot run in between sleep.

Since it changes the process state, it needs ptable.lock.

Then switching to other process.

proc.c

417 void

418 sleep(void *chan, struct spinlock *lk)

419 {

420 struct proc *p = myproc();

421

422 if(p == 0)

423 panic("sleep");

424

425 if(lk == 0)

426 panic("sleep without lk");

427

428 // Must acquire ptable.lock in order to

429 // change p->state and then call sched.

430 // Once we hold ptable.lock, we can be

431 // guaranteed that we won't miss any wakeup

432 // (wakeup runs with ptable.lock locked),

433 // so it's okay to release lk.

434 if(lk != &ptable.lock){ //DOC: sleeplock0

435 acquire(&ptable.lock); //DOC: sleeplock1

436 release(lk);

437 }

438 // Go to sleep.

439 p->chan = chan;

440 p->state = SLEEPING;

441

442 sched(); //goes to scheduler context: 347 line of scheduler().

443

444 // Tidy up.

445 p->chan = 0;

446

447 // Reacquire original lock.

448 if(lk != &ptable.lock){ //DOC: sleeplock2

449 release(&ptable.lock);

450 acquire(lk);

451 }

452 }Wait/Exit

When a parent calls wait(), it scans through the table looking for exited childrent. If there is no exited children, parent goes to sleep which later causes context switching.

proc.c

272 int

273 wait(void)

274 {

275 struct proc *p;

276 int havekids, pid;

277 struct proc *curproc = myproc();

278

279 acquire(&ptable.lock); //since it will change the process state

280 for(;;){

281 // Scan through table looking for exited children.

282 havekids = 0;

283 for(p = ptable.proc; p < &ptable.proc[NPROC]; p++){

284 if(p->parent != curproc || p->pgdir == curproc->pgdir)

285 continue;

286 havekids = 1;

287 if(p->state == ZOMBIE){

288 // Found one.

...clear child memory and state...

298 release(&ptable.lock);

299 return pid;

300 }

301 }

302

303 // No point waiting if we don't have any children.

...

309 // Wait for children to exit. (See wakeup1 call in proc_exit.)

310 sleep(curproc, &ptable.lock); //DOC: wait-sleep, still hold ptable.lock

311 }

312 }sleep will start from here at scheduler() and scheduler will loop to find next RUNNABLE process.

proc.c

347 switchkvm(); //scheduler context starts from here

348

349 // Process is done running for now.

350 // It should have changed its p->state before coming back.

351 c->proc = 0;

352 }

353 release(&ptable.lock);

354

355 }

356 }after switching to child process, when child process calls exit(), it will acquire ptable.lock and calls wakeup1 to wake up the sleeping parent process.

It is possible to acquire the lock because that there is release call after the call to sched in yield, sleep, and exit. Otherwise, in case of the newly created process, forkret release the ptable.lock.

-> The switched process will first release the ptable.lock as it is likely to have been yielded before.

proc.c

250 acquire(&ptable.lock);

251

252 // Parent might be sleeping in wait().

253 wakeup1(curproc->parent);