Flask나 Django로 만든 파이썬 앱을 배포할 때, 보통 Nginx와 Gunicorn과 자기 앱을 연결해서 배포하는 게 정석처럼 여겨진다. 여기서 Nginx를 Apache로, Gunicorn을 uWSGI로 바꿔도 상관없다.

그런데 얘네가 뭐길래? 하는 의문이 든다. Nginx와 Apache는 웹 서버라는 이야기를 들어서 알겠다. 클라이언트의 요청을 받고 앱에 전달해서 앱의 response를 다시 클라이언트에게 전달해주는 역할이라는 것도 알겠다.

그러면 Gunicorn과 uWSGI는 뭐지? 얘네는 왜 있는 걸까? 없어도 되는 건가? 하는 생각이 들기 마련이다. 실제로 Gunicorn을 쓰지 않고 Nginx로만 배포한다는 소리도 들었다. 여기서 Gunicorn은 없어도 되지만 있으면 좋은 미들웨어구나, 하고 생각했다.

그런데 Nginx 없이 Gunicorn으로만 배포한다는 소리를 들었다.

???

웹 서버의 역할을 하는 Nginx가 없어도 가능한건가? 하는 생각이 들었다. 그래서 Nginx, Gunicorn이 도대체 무슨 일을 하는 애들이고, 파이썬 앱과 어떻게 연결되어서 동작하는 것인지 알아보고자 한다.

Nginx, gunicorn, Django가 모두 서버 역할을 하고 있기 때문에, 이렇게 나눠져 있는 서버의 계층 시스템과 WSGI라는 것에 대해 먼저 알아볼 필요가 있다.

1. WSGI의 등장 배경

3계층 시스템과 CGI

3계층 서버 시스템에 대해 들어본 적 있을 것이다. DB 서버는 차치하고 웹 서버와 어플리케이션 서버만 살펴보자. 초기에는 웹 서버만 있었다. 하드웨어에 파일과 이미지를 저장해두었다가 클라이언트로부터 요청이 들어오면 요청한 파일을 화면에 띄워주는 형식이었다.

이런 방식은 빠르고 편했지만 Only Static, 정적인 파일밖에 건네줄 수가 없었다. 그런데 클라이언트로부터 오는 요청이 다양하고 복잡해지면서 로직으로 구현해야 하는 동적인 파일에 대한 요청이 생겨나게 되고, 이런 정적인 파일만으로는 한계를 느끼게 되었다.

그래서 등장한 게 웹 어플리케이션 서버이다. 데이터 파일을 저장해두는 대신, 소스 스크립트를 서버에 저장해놓고 요청이 올 때마다 스크립트를 실행시켜 결과를 반환해주는 것이다. 쉽게 말해 소스 스크립트가 있는 웹 앱 자체를 클라이언트의 요청을 받는 웹 서버로 사용하는 것이다.

그런데, 여기서 파이썬 스크립트가 어떻게 HTTP 요청을 받을 것인가, 하는 문제가 발생한다.

HTTP 요청은 기본적으로 GET /home.html HTTP/1.1 과 같은 텍스트이고, 이는 파이썬 앱이 받는 request object의 형식과는 다르기 때문이다.

그래서 클라이언트로부터 오는 HTTP 요청을 파이썬 스크립트가 요구하는 데이터 형식으로 변환하고 응답을 돌려줄 때도 파이썬 데이터를 HTTP 형식으로 바꿔주는 작업이 필요한데, 이 때 파이썬 앱 서버가 동작하는 기본적인 방식이 CGI, Common Gateway Interface이다.

즉, CGI란 파이썬 어플리케이션 서버의 동작 방식에 대한 specification(사양, 매뉴얼)이라고 할 수 있고 그 기본적인 동작 과정은 다음과 같다.

- 인풋으로 HTTP 요청을 받는다.

- 요청에 대한 정보를 환경변수의 형식으로 만들어서 파이썬 스크립트의 stdin 형식의 인풋으로 받는다.

- 스크립트가 print와 같은 stdout 형식으로 응답하면 HTTP 형식으로 변환된다.

WSGI의 등장

그런데 CGI는 한 가지 문제점이 있었는데, 바로 요청이 들어올 때마다 파이썬 스크립트를 처음부터 실행한다는 것이었다. 이렇게 되면 서버가 너무 느리고 효율도 좋지 않았다.

이 때 등장한 게 WSGI(Web Server Gateway Interface)이다. CGI처럼 WSGI 또한 웹 어플리케이션 서버의 동작 방식에 대한 specification인데, 기본적인 아이디어는 다음과 같다.

웹 서버와 파이썬 스크립트를 분리하고 웹 서버가 클라이언트의 요청을 받아서 스크립트에 전달해주면 스크립트는 스크립트 전체를 실행시키는 게 아니라 필요한 로직 하나만 실행한 후 결과를 응답해주는 식으로 동작함으로써 동적인 콘텐츠에 대한 요청에 빠르게 응답할 수 있게 한 것이다.

이러한 WSGI가 표준적인 파이썬 어플리케이션 서버의 동작 방식이 됨에 따라, WSGI 서버가 클라이언트의 요청을 받는 웹 서버의 역할을 하게 되고 WSGI compatible한 파이썬 앱이 WSGI 서버와 합쳐져서 웹 어플리케이션 서버가 되게 된다.

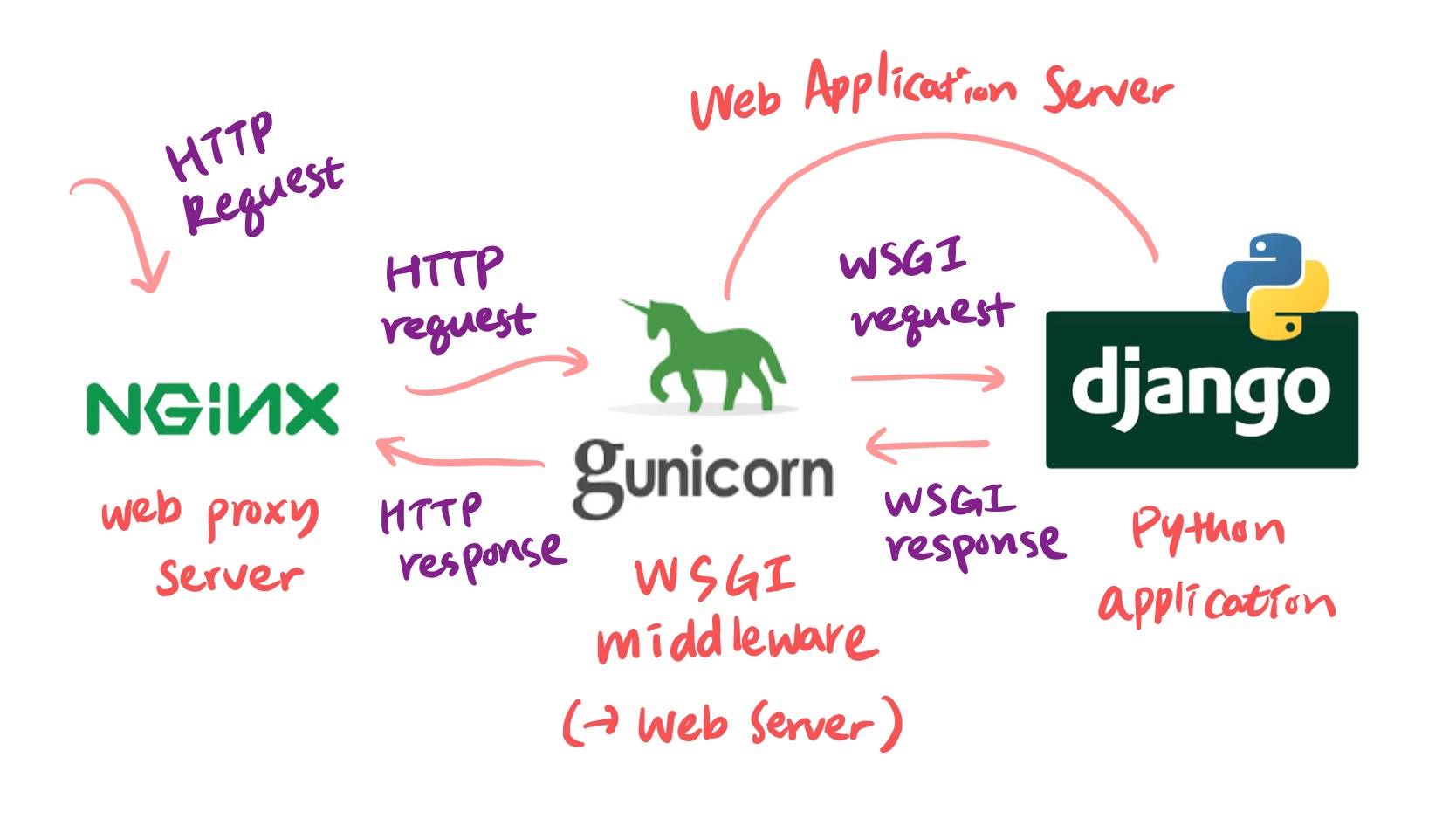

즉, 여기서 WSGI 서버의 역할을 수행하는 애가 Gunicorn이고, Django는 파이썬 앱이라고 할 수 있으며, 얘네가 함께 웹 어플리케이션 서버가 되는 것이다. Nginx는 여기서 Gunicorn+Django의 앞단에 위치하고 있는데, WSGI의 프로세스와는 별 관련 없이 buffering, reverse proxy나 load balance와 같은 별도의 일을 수행하게 되는 것이다.

2. WSGI의 동작 과정

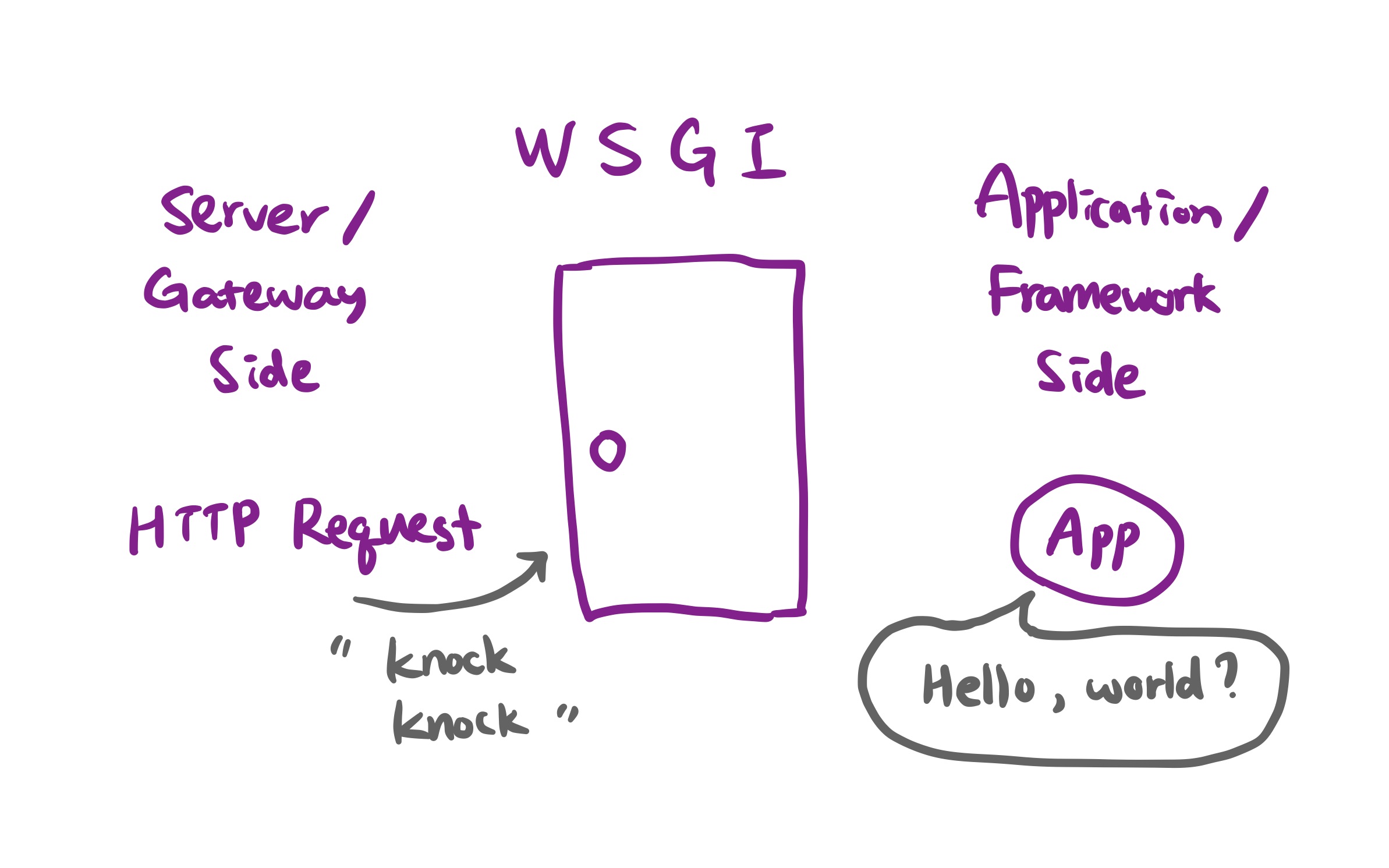

WSGI에 대해 좀 더 감을 잡기 위해 PEP333에 나와있는 WSGI의 동작 과정을 한 번 살펴보려고 한다. 다시 한 번 말하지만 WSGI는 별도의 프레임워크 같은 게 아니라, 동적인 데이터에 대응하기 위해서 웹 서버와 파이썬 웹 앱이 어떻게 서로 동작해야 하는지에 대한 내용을 담고 있는 specification이라고 할 수 있다.

공식 문서에서는 WSGI를 "simple and universal interface between web servers and web applications or frameworks"라고 설명하고 있으며, WSGI의 목적은 "to facilitate easy interconnection of existing servers and applications or frameworks, not to create a new web framework"라고 서술하고 있다.

WSGI는 server/gateway side와 application/framework side를 가지는데, server side에서 들어온 요청이 application side의 callable object를 호출(invoke)하게 된다. 여기서 callable object란 곧 파이썬 스크립트에서 정의한 application을 의미하고, object라고는 했지만 callable한 어떤 형태든지 상관은 없다.

각각의 코드를 한 번 살펴보자.

Application/Framework Side

다음은 함수 형태의 application이다.

def application(environ, start_response):

"""Simplest possible application object"""

status = '200 OK'

response_headers = [('Content-type', 'text/plain')]

start_response(status, response_headers)

return ['Hello world!\n']- application은 environ 객체와 start_response라는 콜백함수를 인자로 받는다.

- environ은 method나 url 등 HTTP 요청에 대한 정보를 CGI 환경 변수의 형식으로 담고 있는 dictionary 형태의 객체라고 할 수 있다.

- start_response 콜백 함수는 status와 response_headers라는 두 가지 인자를 받는다.

- status에는

200 OK와 같은 HTTP status 코드가 들어가고, response_headers에는 HTTP 헤더가 들어간다.

Server/Gateway Side

server side에서는 클라이언트의 요청이 올 때마다 application을 호출한다.

import os, sys

def run_with_cgi(application): # application을 인자로 받음

# environ 객체

environ = dict(os.environ.items())

environ['wsgi.input'] = sys.stdin # stdin의 형태로 input을 받음

environ['wsgi.errors'] = sys.stderr

environ['wsgi.version'] = (1, 0)

environ['wsgi.multithread'] = False

environ['wsgi.multiprocess'] = True

environ['wsgi.run_once'] = True

if environ.get('HTTPS', 'off') in ('on', '1'):

environ['wsgi.url_scheme'] = 'https'

else:

environ['wsgi.url_scheme'] = 'http'

headers_set = []

headers_sent = []

def write(data):

if not headers_set:

raise AssertionError("write() before start_response()")

elif not headers_sent:

# Before the first output, send the stored headers

status, response_headers = headers_sent[:] = headers_set

sys.stdout.write('Status: %s\r\n' % status)

for header in response_headers:

sys.stdout.write('%s: %s\r\n' % header)

sys.stdout.write('\r\n')

sys.stdout.write(data)

sys.stdout.flush()

# status와 response_headers를 받는 start_response 콜백함수

def start_response(status, response_headers, exc_info=None):

if exc_info:

try:

if headers_sent:

# Re-raise original exception if headers sent

raise exc_info[0], exc_info[1], exc_info[2]

finally:

exc_info = None # avoid dangling circular ref

elif headers_set:

raise AssertionError("Headers already set!")

headers_set[:] = [status, response_headers]

return write

result = application(environ, start_response)

try:

for data in result:

if data: # don't send headers until body appears

write(data)

if not headers_sent:

write('') # send headers now if body was empty

finally:

if hasattr(result, 'close'):

result.close() 참고 WSGI Middleware

- WSGI server/gateway side와 application/framework side를 둘 다 구현하고 있는 하나의 프로그램

- 서버에 대해서는 어플리케이션의 역할을 수행하고, 어플리케이션에 대해서는 서버의 역할을 수행.

- 동작 과정 : 클라이언트 요청 → server side에서 middleware component를 호출 → middleware component가 application side의 application을 호출

- Gunicorn, uWSGI

3. Framework의 WSGI application

이번에는 대표적인 파이썬 프레임워크인 Django와 Flask에 내장된 WSGI application을 한 번 살펴보려고 한다.

Django

📁 django project를 생성하면 자동으로 만들어지는 wsgi.py 파일

"""

WSGI config for movie_project project.

It exposes the WSGI callable as a module-level variable named ``application``.

For more information on this file, see

https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/3.1/howto/deployment/wsgi/

"""

import os

from django.core.wsgi import get_wsgi_application

os.environ.setdefault('DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE', 'movie_project.settings')

application = get_wsgi_application()📁 django.core.wsgi.py

import django

from django.core.handlers.wsgi import WSGIHandler

def get_wsgi_application():

"""

The public interface to Django's WSGI support. Return a WSGI callable.

Avoids making django.core.handlers.WSGIHandler a public API, in case the

internal WSGI implementation changes or moves in the future.

"""

django.setup(set_prefix=False)

return WSGIHandler()📁 django.core.handlers.wsgi.py

class WSGIHandler(base.BaseHandler):

request_class = WSGIRequest

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

self.load_middleware()

def __call__(self, environ, start_response):

set_script_prefix(get_script_name(environ))

signals.request_started.send(sender=self.__class__, environ=environ)

request = self.request_class(environ)

response = self.get_response(request)

response._handler_class = self.__class__

status = '%d %s' % (response.status_code, response.reason_phrase)

response_headers = [

*response.items(),

*(('Set-Cookie', c.output(header='')) for c in response.cookies.values()),

]

start_response(status, response_headers)

if getattr(response, 'file_to_stream', None) is not None and environ.get('wsgi.file_wrapper'):

# If `wsgi.file_wrapper` is used the WSGI server does not call

# .close on the response, but on the file wrapper. Patch it to use

# response.close instead which takes care of closing all files.

response.file_to_stream.close = response.close

response = environ['wsgi.file_wrapper'](response.file_to_stream, response.block_size)

return responseFlask

📁 flask app.py

from flask import Flask

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route("/")

def hello():

return "Hello World!"

if __name__ == "__main__":

app.run()📁 flask.src.flask.app.py

class Flask(Scaffold):

"""The flask object implements a WSGI application and acts as the central

object. It is passed the name of the module or package of the

application. Once it is created it will act as a central registry for

the view functions, the URL rules, template configuration and much more.

The name of the package is used to resolve resources from inside the

package or the folder the module is contained in depending on if the

package parameter resolves to an actual python package (a folder with

an :file:`__init__.py` file inside) or a standard module (just a ``.py`` file).

"""

def wsgi_app(self, environ, start_response):

"""The actual WSGI application. This is not implemented in

:meth:`__call__` so that middlewares can be applied without

losing a reference to the app object. Instead of doing this::

app = MyMiddleware(app)

It's a better idea to do this instead::

app.wsgi_app = MyMiddleware(app.wsgi_app)

Then you still have the original application object around and

can continue to call methods on it.

:param environ: A WSGI environment.

:param start_response: A callable accepting a status code,

a list of headers, and an optional exception context to

start the response.

"""

ctx = self.request_context(environ)

error = None

try:

try:

ctx.push()

response = self.full_dispatch_request()

except Exception as e:

error = e

response = self.handle_exception(e)

except: # noqa: B001

error = sys.exc_info()[1]

raise

return response(environ, start_response)

finally:

if self.should_ignore_error(error):

error = None

ctx.auto_pop(error)

def __call__(self, environ, start_response):

"""The WSGI server calls the Flask application object as the

WSGI application. This calls :meth:`wsgi_app`, which can be

wrapped to apply middleware.

"""

return self.wsgi_app(environ, start_response)4. 정리

✔ Gunicorn은 왜 필요한가? 웹 앱에 HTTP 요청을 전달하고 응답을 되돌려주는 일을 할 WSGI server의 역할을 하기 위해서 → WSGI middleware

✔ Nginx는 왜 필요한가? reverse proxy server, load balancer 등의 역할을 수행하기 위해서

✔ Django/Flask는 왜 필요한가? WSGI compatible server를 알아서 제공해주기 때문이다. raw WSGI application을 만들 수는 있지만 기능을 일일이 다 구현하기 번거롭고 너무 많은 코너 케이스가 존재하기 때문에 권장하지는 않는다. 그래서 이미 session이나 cookie와 같은 많은 부분이 구현되어 있는 프레임워크를 쓰는 것이다.

✔ 그럼 그냥 프레임워크 서버를 웹 서버로 사용하면 되지 않을까? 그래도 안될 건 없다. 하지만 보통은 그러지 않는다. 프레임워크가 제공하는 development server는 실제 트래픽에 대응할 수 없고 여러 부분에서 빈약하기 때문이다. Flask 앱을 만들 때 flask run을 통해 서버를 실행시키면 터미널에 production server용으로는 쓰지 말라는 메세지가 나오는 이유도 이 때문이다.

그래서 결론은?

✅ Gunicorn만 써도 돼? YES.

Gunicorn이 WSGI middleware로서 웹 서버의 역할을 수행하기 때문에 Gunicorn만 써도 된다. 다만, Nginx가 제공하는 추가적인 혜택을 받지 못할 뿐이다.

✅ Nginx만 써도 돼? YES.

Flask나 Django 같은 프레임워크는 WSGI interface를 이미 어느 정도 구현해놓았기 때문에 프레임워크를 사용한다면 Nginx만 써도 된다. 다만 session, cookie, routing, authentication 등의 기능을 수행해주는 middleware의 역할을 하는 애가 없기 때문에 이 부분은 자기가 하드 코딩해야 한다. 결국, Gunicorn/uWSGI를 사용하는 것도 편리한 기능들을 제공해주는 라이브러리를 가져다 쓰는 것과 똑같다고 할 수 있고, 반드시 써야만 하는 건 아니다.

참고 자료

- https://youtu.be/WqrCnVAkLIo

- https://youtu.be/H6Q3l11fjU0

- https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0333/#specification-overview (PEP333)

- https://www.nginx.com/resources/glossary/application-server-vs-web-server/

- https://www.fullstackpython.com/green-unicorn-gunicorn.html#:~:text=Gunicorn is based on a,is independent of the controller.

- https://sgc109.github.io/2020/08/15/python-wsgi/

- http://xplordat.com/2020/02/16/a-flask-full-of-whiskey-wsgi/

더 알아보고 싶은 내용

- ASGI : https://youtu.be/uRcnaI8Hnzg

여태까지 찾아봤던 글 중에 가장 잘 정리되어있는 것 같아요. 감사합니다. 처음 장고를 배포한다고 uwsgi를 끄적거린 뒤로 거의 2년이 된 것 같은데 항상 '불안하대', '장고에서 보장 못한대' 이런 이유만 봤지 이렇게 잘 정리된 글은 처음이네요..!