Speed comparison between CPU vs Memory

Since the advent of CPUs and memory, there has never been a time when memory outpaced the speed of the CPU. In fact, the gap between their speeds has only widened over time.

So, if CPUs are always faster than memory, how do we bridge this speed gap? The answer lies in cache.

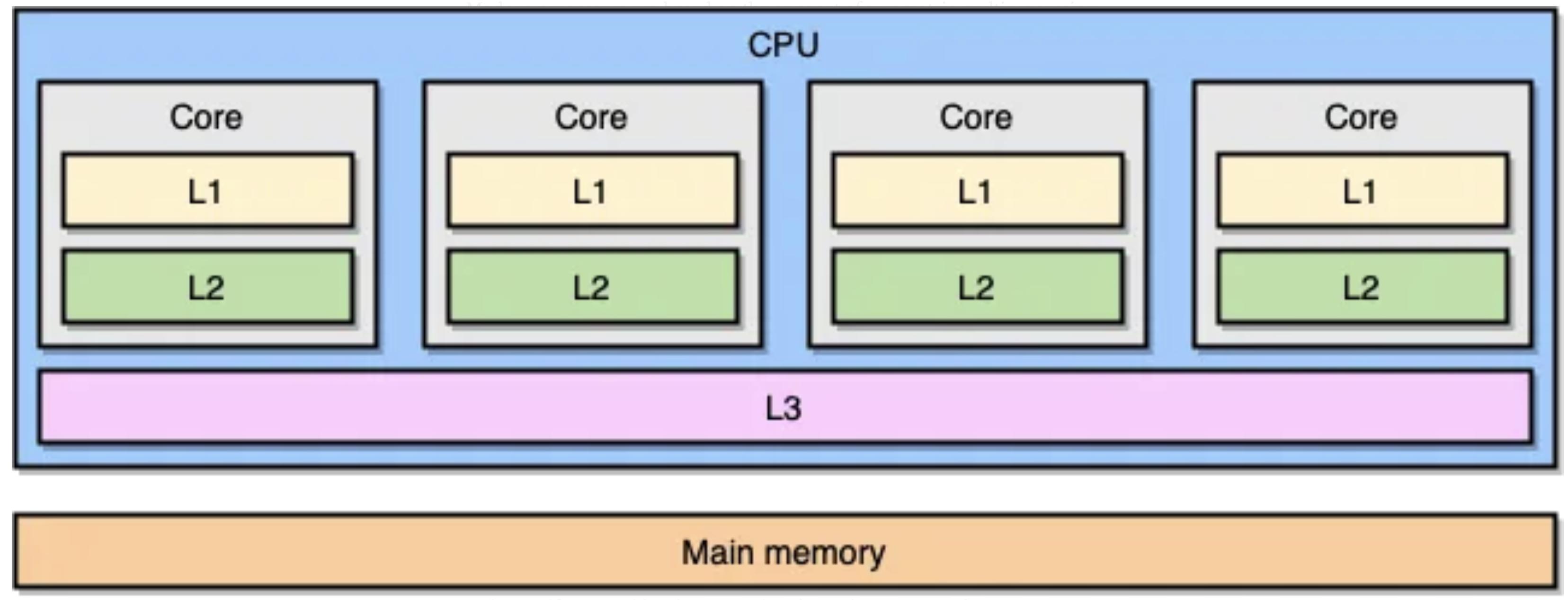

At the time of writing(2024, 1st Oct), most of modern CPUs come equipted with three layers of caches(L1, L2, L3) and it works as the time that it takes to access data from these caches ranges from 4 to 50 clock cycles - the further away the cache is from the CPU, the slower it is.

You can think of cache like a desk in a library. You pick a book from a shelf(memory) and when you want to read, you just open the book on the desk(cache).

But it is not as easy

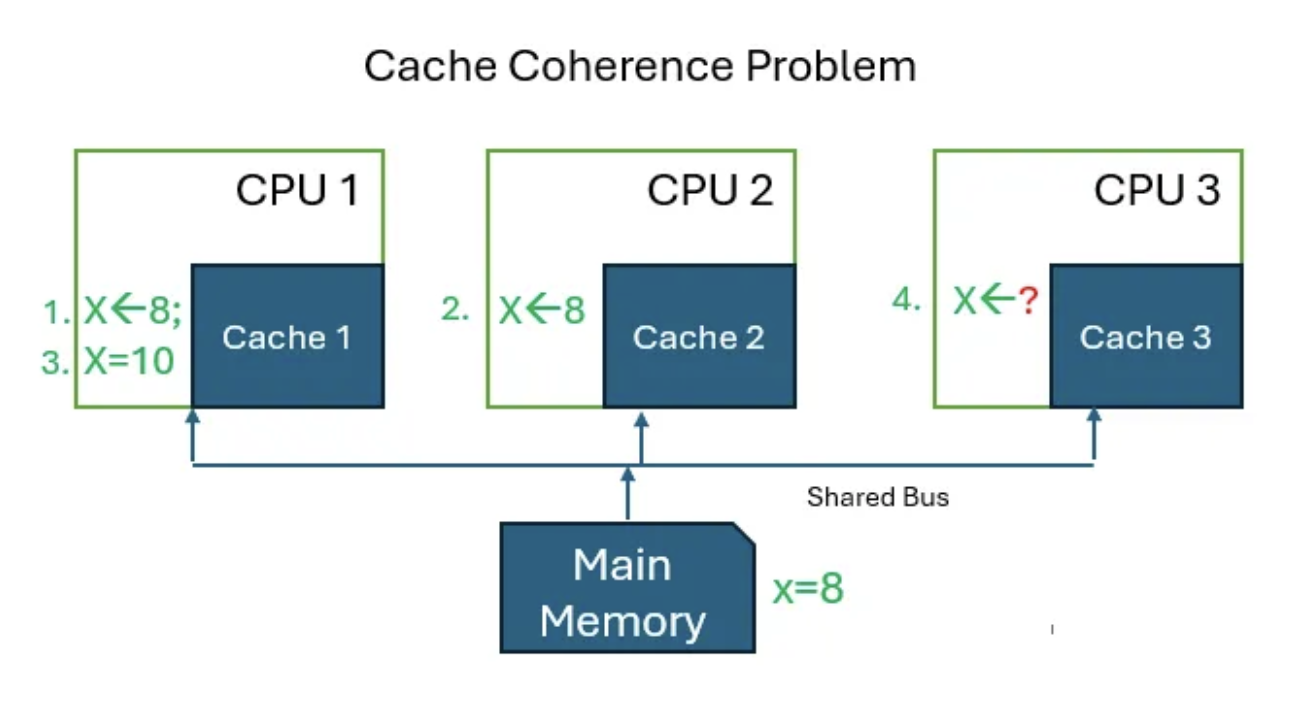

The problem happens when we write something. CPUs do not write things directly interact with memory. So for the fleeting moment, data on memory becomes stale - inconsistency issue.

Write-through

The easiest solution to this is to update memory when we do to cache(write through). But then in that case, CPUs have to wait until memory is updated and this is a rather synchoronous architecture.

Write-back

Instead of waiting for memory updates, CPUs can continue executing instructions. However, cache has limited storage capacity, meaning data must eventually be removed from cache. When this happens, if we’ve set a flag indicating a state update for data in question, we can simply write the updated data back to memory as it’s removed from the cache. This technique is known as "write-back."

Insistency in multicore architecture

With all the techniques like write-through and write-back, another problem appeared when we transitioned multicore systems.

The solution to this problem involves updating caches on other cores which, as you might expect, can be costly.

You may wonder how this impacts the way you program as a developer. While the full discussion goes beyond the scope of this article, I’ll revisit it in more detail later.