Synchronizing asynchronous tasks in JavaScript was a serious issue for a very long time.

CallBack

callbacks are just the functions passed in as an argument which you want them to be called after some operation is done

function add(x,y,callback){

const sum = x+y;

callback(sum);

};

add(2,3,function(sum){

console.log('sum',sum); //sum 5

});this is fairly simple all we need to do is pass in a function which we want to execute after the asynchronous operation is done But,the major problem this approach introduces is when we want to do multiple asynchronous calls and we have to do them one after the another... it introduced what is popularly known as call-back hell. looks similar to below code:

getData(function(a){

getMoreData(a, function(b){

getMoreData(b, function(c){

getMoreData(c, function(d){

getMoreData(d, function(e){

...

});

});

});

});

});since every async call depended on the data fetched from the previous call it had to wait for the previous one to complete. This works but it was very hard to debug and maintain.

Promises/Async & Await

Promise

Promises are introduced in es6 and solved some of the problems of callbacks.

Promises enable asynchronous programming in Javascript. A promise creates a substitute for the awaited value of the asynchronous task and lets asynchronous methods return values like synchronous methods. Instead of immediately returning the final value, the asynchronous method returns a promise to supply the value at some future point

The constructor syntax for a promise object is:

let promise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

// executor (the producing code, "hello")

});The function passed to the new promise is called the executor. When a new promise is created, the executor runs automatically. It contains the producing code which should eventually produce the result. In terms of the analogy above: the executor is the “hello”

Its arguments resolve and reject are callbacks provided by javascript itself. The code above is only inside the executor.

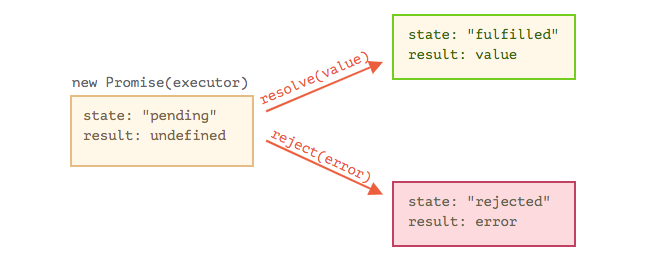

When the executor obtains the result, be it soon or late, doesn’t matter, it should call one of these callbacks:

resolve(value)- if the job finished successfully, with result value.

reject(error) - if an error occurred, error is the error object.

So to summarize: the executor runs automatically and attempts to perform a job. When it is finished with the attempt it calls resolve if it was successful or reject if there was an error.

The promise object returned by the new Promise constructor has these internal properties:

State - initially pending, then changes to either fulfilled when resolve is called or rejected if there was an error.

Chained promises

const fetchLatestDevToNewsPromiseChaining = () => {

return fetch('https://dev.to/api/articles?per_page=5&tag=security')

.then(response => response.json())

.then(latestArticles => keyDevToInfo(latestArticles))

.catch(err)

};JavaScript’s built-in Fetch API returns a promise object which we can then chain promise methods on to, in order to handle the response.

Async / Await

The other approach is to use async/await. We use async on the function declaration and then await immediately before the request to the API. Rather than using the promise methods to handle the response, we can simply write any further handling in the same way as other synchronous Javascript.

const fetchLatestDevToNewsAsyncAwait = async () => {

try {

const response = await fetch("https://dev.to/api/articles?per_page=5&tag=security")

const latestArticles = await response.json()

return keyDevToInfo(latestArticles)

} catch (err) {

return err

}

}As we are not using promise methods here we should handle any rejected promises using a try/ catch block.

What you’ll notice in both cases is that we don’t need to literally create the Promise object: most libraries that assist with making a request to an API will by default return a promise object. It’s fairly rare to need to use the Promise constructor.

Handling promises

Promise.all

Promise.all([fetchLatestDevToNewsPromiseChaining(), fetchLatestDevToNewsAsyncAwait()])

.then(([chained, async]) => {

createFile([...chained, ...async])

})Promise.all is a good option for asynchronous tasks that are dependent on another. If one of the promises is rejected, it will immediately return its value. If all the promises are resolved you’ll get back the value of the settled promise in the same order the promises were executed.

This may not be a great choice if you don’t know the size of the array of promises being passed in, as it can cause concurrency problems.

Promise.allSettled

Promise.allSettled([fetchLatestDevToNewsPromiseChaining(), fetchLatestDevToNewsAsyncAwait()])

.then(([chained, async]) => {

createFile([...chained, ...async])

})Promise.allSettled is handy for asynchronous tasks that aren’t dependent on one another and so don’t need to be rejected immediately. It’s very similar to Promise.all except that at the end you’ll get the results of the promises regardless of whether they are rejected or resolved.

Promise.race

Promise.race([fetchLatestDevToNewsPromiseChaining(), fetchLatestDevToNewsAsyncAwait()])

.then(([chained, async]) => {

createFile([...chained, ...async])

})Promise.race is useful when you want to get the result of the first promise to either resolve or reject. As soon as it has one it will return that result - so it wouldn’t be a good candidate to use in this code.

So, should I use chained promises or async/await?

What’s the difference between these two approaches? Not much: choosing one or the other is more of a stylistic preference.

Using async / await makes the code more readable and easier to reason about because it reads more like synchronous code. Likewise, if there are many subsequent actions to perform, using multiple chained promises in the code may be harder to understand.

On the other hand, it could also be argued that if it’s a simple operation with few subsequent actions chained then the built in .catch() method reads very clearly.

Whichever approach you take, thank your lucky stars that you have the option to avoid callback hell!

Nice Blog!! Async/Await memo...