- We took the

perspectiveof a potential investor who tries to deciede whether to build anew generating plant - We also considered the decision process of the owner of a plant who is trying to decide whether the time has come to shut it down

- In this section, we consider the

provisionof generation capacity from the consumers' perspective - In a

completelyderegulated environment, there is noobligationon any company to build power platns - The total generation capacity that is available for

supplyingthedemandtherefore arises from individual decisions based on perceptions ofprofit opportunities

Expansion Driven by the Market for Electrical Energy

-

Some power system economists insist that electrical energy should be treated like any other commodity.

- If electrical energy is traded on a free market, there is no need for a

centralizedmechanism for controlling or encouraging investments in generating plants - If left alone, markets will determine the

optimallevel of production capacity called for by the demand - Interfering with the market

distortsprices and incentives Centralizedplanning and subsidies lead to overinvestment or underinvestment, both of which are economicallyinefficient

- If electrical energy is traded on a free market, there is no need for a

-

If the demand for a commodity

increases, or its supplydecreases, the resulting upswing in market priceencouragesadditional investments in production capacity and a new long-run equilibrium is ultimatelyreached -

Because of the cyclical nature of the demand for electricity and its lack of elasticity, price

increaseson electricity markets are usually notsmoothandgradual -

Instead, we are likely to observe price

spikeswhen the demand approaches the total installed generation capacity

-

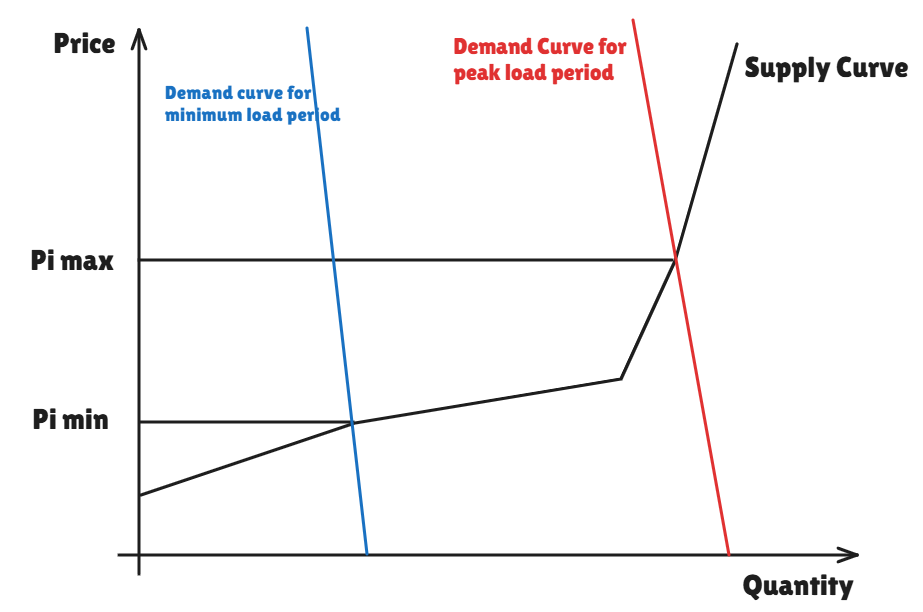

The figure illustrates this phenomenon

-

A typical supply function is represented by a stylized, three-segment, piecewise

linearcurve- The first, moderately sloped, segment represents the bulk of the generating units in a resonably

competitivemarket - The second segment, which has a much

steeperslope, represents the peaking units that are calledinfrequently - The third segment is

verticaland represents the supply function when all the existing generation capacity is in use

- The first, moderately sloped, segment represents the bulk of the generating units in a resonably

-

An almost vertical line represents the

low-elasticitydemand function -

This demand function moves horizontally as the demand fluctuates over time

-

Two curves are shown :

- One representing the minimum demand period

- The other the peak demand period

-

The intersections of these curves with the supply function determine the

minimumand themaximumprices

- When the generation capacity is tight but

sufficientto meet the load :First figure

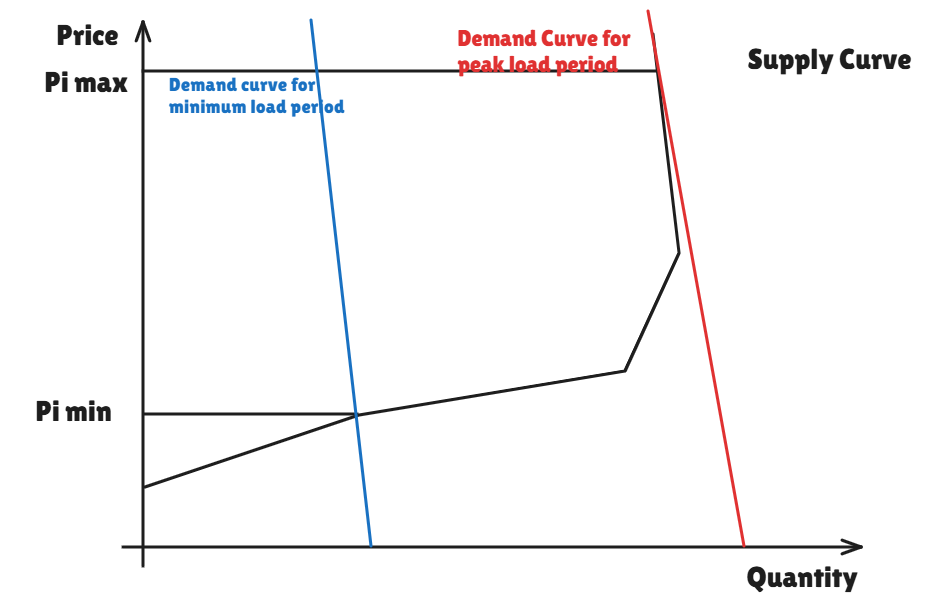

The price rises sharply during periods of peak demand because the market price is determined by the bids of generating units that operate very infrequently - These price spikes are much higher when all the generation capacity is in use under peak load conditions :

Second figure

- Such a situation could happen because the installed generation capacity has not kept up with the load growth, because some generation capacity has been retired or because some generation capacity is unavailable

- Under these conditions, the only factor that would limit the price increase is

elasticityof the demand

In pratice, these price splikes are significantly higher than what

Figuresuggests, and they aresufficientto substantially increase the average price of electricity even if they occur onlya few times a year

- These price spikes are

obviously very expensive(one might say painful) for the consumers - They should thus encourage them to become more responsive to price signals

- As the price

elasticityof the demandincreases, the magnitude of the spikesdecreases, even if the balance between peak load and generation capacity does notimprove - Price spikes also give consumers a

strong incentiveto enter into contracts thatencourage generators to investin genration capacity

- In conclusion, it appears that relying solely on the market for electrical energy and its price spikes to bring about enough generation capacity is

unlikely to give satisfactory results - This approach presumes that consumers are only buying electrical energy and that this transaction can be treated as the purchase of a commodity

- In pratice, consumers do not purchase only electrical energy but a service that can be defined as the provision of electrical energy with a certain level of

reliability

Capacity Payments

- The rist associated with leaving generation investments to the invisible hand of the delctrical energy market has often been judged to be

too great - Market designers in several countries and regions have decided that, rather than occasionally paying generators large amounts of money because of shortage-induced price spikes, it was preferable to pay them a

smaller amounton a regular basis

- Capacity payments thus reduce the risks described in the previous section and spread them among all consumers, irrespective of the timing of their demand for electrical energy.

- At least in the short term, this socialization of the cost of peaking energy benefits the risk-averse market participants, whether they are consumers or producers.

- In the long term, this approach reduces the

incentivefor economically efficient behavior: too much capital may be invested in generation capacity and too little on devices that consumers could use to control their demand

- In an attempt to get around these difficulties, the Electricity Pool of England and Wales adopted an alternative approach

- The centrally determined price of electrical energy during each period was increased by a capacity element equal to :where is the Value of Lost Load and is the Loss of Load Probability during period

- Since this probability depends on the

marginbetween the load and the available capacity and on the outage rates of the units, this capacity element fluctuated from one period to the next and occasionally caused significant price spikes

Capacity Market

- Rather than fixing the total amount or the rate of capacity payments, some regulatory authorities set a generation adequacy target and determine the amount of generation capacity required to achieve this target

- All energy retailers and large consumers are then obligated to buy their share of this requirement on an organized capacity market

- While the amount of capacity to be purchased on this market is determined administratively, its price depends on the capacity on offer and may be quite volatile

- Implementing a capacity market that achieves its purpose is not a simple matter

- The first, and probably most fundamental, of these issues is the length of the market periods.

- Retailers prefer a shorter period because it reduces the amount of capacity that they have to purchase during periods of light load

- A shorter period also increases the liquidity of the capacity market

- On the other hand, a longer period favors generators and encourages the building of new capacity

- In an interconnected system, it discourages existing generators from selling their capacity in a neighboring market

- A

longer periodalso matches more closely the frequency at which the regulatory authorities evaluate the reliability of the system

- The installed generation capacity must exceed the peak demand because generaotrs can fail at any time

- Unreliable generators therefore increase the size of the required generation capacity margin and impose a cost on the entire system

- An energy buyer who does not purchase its share of the target generation capacity benefits from the the installed capacity margin paid for by the other market participants

- It also has a cost advantage in the energy market

- A deficiency payment or penalty must therefore be imposed on any entity that does not meet its obligations

- The level of this payment and the rules for its imposition must be set in a way that encourages proper behavior and discourages free riders

- Some electricity markets have started to include the demand side in their capacity markets

- In these markets, large consumers or entities who aggregate a sufficient number of small consumers bid their ability to reduce their demand when requested by the system operator

Reliability Contracts

- Ideally, every consumer should decide freely and independently how much it is willing to pay for reliability

- Until electricity markets achieve the level of maturity where this approach becomes possible, a central authority could purchase reliability on behalf of consumers

- Instead of setting a target for installed capacity as happens in capacity markets, this central authority could auction reliability contracts as proposed by Vazquez et al.(2002)

- The central authority uses

reliability criteriato determine the total amount of contracts to be purchased and set the strike price of these contracts, typically at above the variable cost of the most expensive generator that is expected to be called - Bids for these contracts are ranked in terms of the premium fee asked by the generators

- The premium fee that clears the

quantityis paid for all contractsLet us consider a generator that has sold an option for MW at a premium

This generator receives a premium fee of for every period of the duration of the contract. For each period during which the spot price of electrical energy exceeds the strike price , this generator must reimburse to the consumers.

If this generator is only producing MW during this period, it must pay an additional penalty of