Coroutine

A typical textbook explanation of threads focuses on kernel threads, over which you rarely have direct control.

From creation to scheduling and termination, a kernel thread is fully managed by the operating system, meaning the programmer has no direct influence. In academic terms, this is known as preemptive threading.

This raises an important question: is there a way to implement threads that aren't reliant on the OS? The answer is yes, through the use of coroutines.

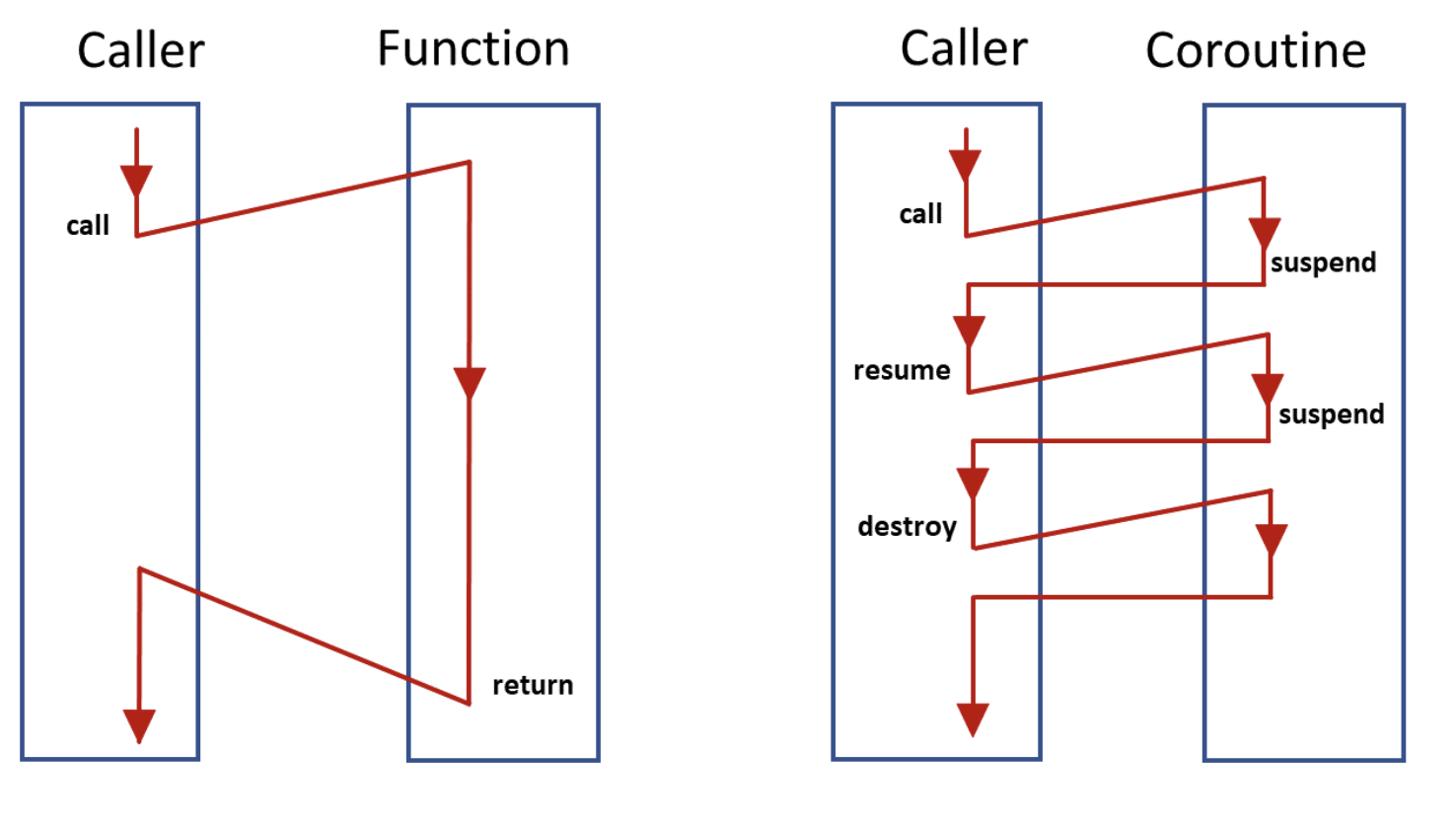

Normal function vs coroutine

The key difference between a function and a coroutine is that a coroutine allows you to pause and resume its execution. What does this mean? Consider the following illustration:

The following is the pseudocode for a coroutine:

fn f(){

print!("a");

yield;

print!("b");

yield;

print!("c");

}So, when instruction hits yield, it give a control back to calling function(consumer of this function) - which is just like a thread yields control back the OS and OS reassign the CPU time to other thread.

Lifetime implication

A typical function does not retain its execution context after hitting a return statement. In contrast, coroutines must store their execution context, as they are expected to resume from where they paused.

At this point you might wonder: how does the execution context handle references to external variables that may not exist?

- Suspended State : When a coroutine is suspended, its entire execution state, including local variables and the point of suspension is saved

- Heap allocation : the state is stored on the heap memory.

- Lifetime : runtime or framework managing the coroutines is responsible for ensuring that any external variables remain valid - which is the trickest part

If an extenral reference goes out of scope, it can potentailly lead to dangling references.

Static verification of the lifetimes - Rust

Rust's ownership system combined with the async/await syntax and the Future trait enables the compiler to statically verify the lifetimes of all references - this prevents many common concurrency bugs at compile time without runtime overhead:

use tokio::time::{sleep, Duration};

async fn process_data(data: &str) -> String {

// Simulate some async work

sleep(Duration::from_secs(1)).await;

format!("Processed: {}", data)

}

#[tokio::test]

async fn success() {

let data = String::from("Hello, World!");

// works fine

let result = process_data(&data).await;

println!("{}", result);

}

#[tokio::test]

async fn not_compiled() {

let result = {

let data = String::from("Hello, World!");

// This closure captures a reference to `data`

let future = process_data(&data);

future

}; // `data` is dropped here

// This will fail to compile

let processed = result.await;

println!("{}", processed);

}

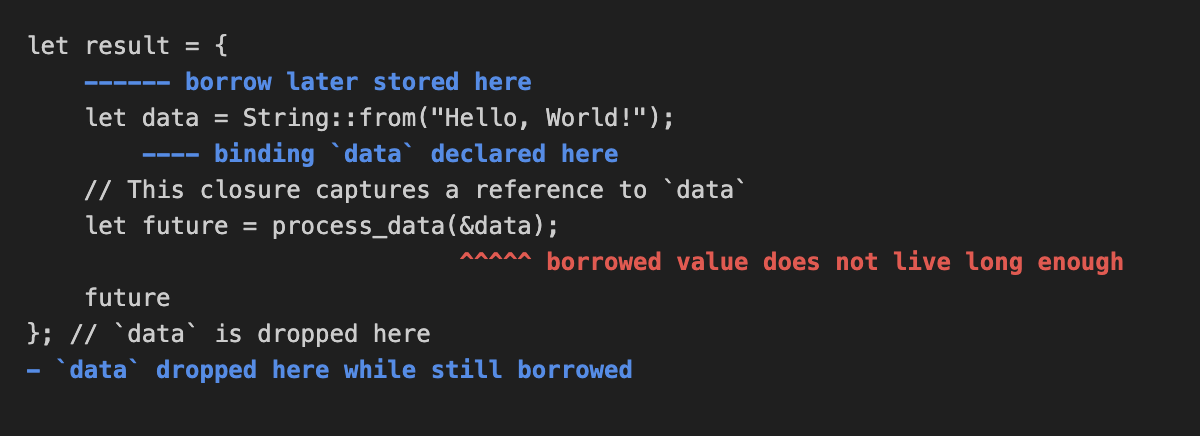

The test not_compiled literally doesn't get compiled (which may be surprising to some who have had to test things out at runtime) as it detects lifetime issue at compile time:

This makes sense because variables are dropped at the end of a block, and when they are dropped, all references to those variables must be nullified—which Rust will not allow.