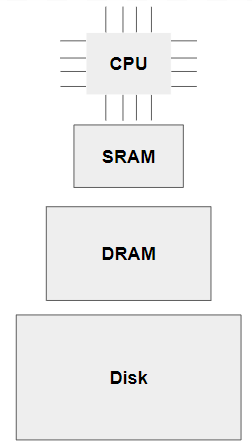

Memory hierarchy is a fundamental concept in computer architecture that helps in managing the trade-off between memory speed and cost. Different types of memory offer varying performance levels. These are organized to create an efficient system that balances speed, capacity, and cost.

The objective of constructing memory hierarchy is to achieve speed of the fastest memory with size of the cheapest memory

The upper hierarchy, the faster and the more expensive

Memory Types

SRAM (Static RAM)

SRAM is a type of volatile memory that retains data as long as power is supplied. It is faster than other types of memory because it doesn't require constant refreshing. However, SRAM is expensive and consumes more power, making it ideal for use in smaller, high-speed caches.

DRAM (Dynamic RAM)

DRAM is slower and less expensive than SRAM, but it is more commonly used for larger memory capacities, such as in the system's main memory (RAM). DRAM needs to be periodically refreshed to retain data. Despite its slower speed, DRAM is essential due to its higher storage capacity and cost efficiency.

Disk (HDD/SSD)

Disks(Hard Disk Drives (HDDs) or Solid State Drives (SSDs)) represent the slowest but largest form of memory in a system. Disks are non-volatile, meaning they retain data even without power. Disks are used for long-term data storage.

Locality

Locality is a key principle in memory access that optimizes system performance by predicting and leveraging the patterns in which data is accessed.

Temporal Locality

Temporal locality refers to the concept that if a piece of data is accessed once, it is likely to be accessed again in the near future. This access pattern is crucial for the effective design of caches, as recently used data can be stored in faster, smaller memory (like SRAM), reducing the need to fetch data from a lower and slower memory layer.

Spatial Locality

Spatial locality suggests that if a particular memory location is accessed, nearby memory locations are likely to be accessed soon. For instance, sequential access to elements in an array shows why spatial locality is effective.

Mechanisms of Exploiting Memory Hierarchy

The memory hierarchy is designed to exploit temporal locality and spatial locality by ensuring frequently accessed data is available in faster memory layers and that less frequently accessed data is moved to slower, larger layers.

Caching Mechanism

The caching mechanism is the heart of how memory hierarchy is exploited. The idea is to keep frequently accessed data (or instructions) in the cache, which is much faster than main memory (DRAM).

- Cache Hits: When the CPU accesses data, the system first checks whether the data is available in the cache. If the data is found (cache hit), it can be accessed quickly without needing to fetch it from a slower memory layer like DRAM.

Memory Access Patterns and Locality

The memory hierarchy leverages locality principles to optimize performance:

- Cache Misses: If the data is not in the cache (cache miss), the system must fetch it from the next slower layer in the hierarchy (typically DRAM). This takes longer, but the fetched data is placed into the cache for future accesses.

- Temporal Locality: Recently accessed data is more likely to be accessed again soon. The cache keeps this data for a short period to ensure quick future access. For example, when the CPU repeatedly accesses the same variable, the cache ensures this variable stays in fast SRAM.

- Spatial Locality: Data near the recently accessed data is likely to be accessed soon. Modern processors exploit this by fetching blocks of data around the accessed memory address into the cache (not just the single byte/word requested). For example, when accessing an array, the entire block of memory containing several elements is fetched into the cache, reducing the number of accesses to DRAM.

Virtual Memory and Paging

Virtual memory provides an illusion that the entire program is loaded onto memory, even if only portions of it are physically present. This allows programs to use more memory than what is physically available on the system.

Memory space is divided into small fixed-size blocks called pages. These pages can be loaded into page frames in physical memory as needed. When a program accesses a memory address, the virtual address is translated into a physical address using a page table, which keeps track of the mapping between virtual pages and physical page frames. This process ensures efficient memory management and isolation between processes.

Replacement Policies

Since cache memory is limited, when new data is loaded into the cache, old data must be evicted to make room. The replacement policy determines which data to evict. Common replacement policies include:

- LRU (Least Recently Used): evicts the data that hasn’t been used for the longest period, assuming that recently used data will be accessed again soon.

- FIFO (First In, First Out): Evicts the oldest data, regardless of whether it was recently used or not.

- Random: Randomly selects data to evict. It seems inefficient but, its simplicity may outperform FIFO and LRU.

7. Write Policies (Write-Through and Write-Back)

Caches also need mechanisms to handle write operations:

- Write-Through: When data is written to the cache, it is immediately written to DRAM as well. This ensures that the cache and main memory are always synchronized but incurs more memory traffic.

- Write-Back: Data is written only to the cache at first, and updates are sent to DRAM only when the cache is evicted. This reduces memory traffic but requires additional complexity to manage such as dirty bits.