What does class mean in javascript? js grammar for class, instance, constructors

Javascript

Is javascipt an object-oriented programming language?

Short answer: no, not really. It is a prototype-based, object-based language but does not exhibit key characteristics of OOP languages, which I should delve into in another post.

It does have ways of using its prototype-based functionality to mimic OOP, and in ES6 you can declare class constructors with the 'class' keyword, but all this seems to be regarded by the developer community largely as, "syntactic sugar. " How js functions in its core has not changed.. but the new syntax does enhance the code's readability and streamlines its operation a bit.

There is still some confusion though because this syntax make sit seem like editing the properties of the class would propagate to its instances, but it does not. Only editing the property of the prototype the instance object is pointing to, would.

Here are some ways the class syntax can be used to construct objects of the same 'class' (blueprint): [mdn]

// Declaration

class Rectangle {

constructor(height, width) {

this.height = height;

this.width = width;

}

// Getter

get area() {

return this.calcArea();

}

// Method

calcArea() {

return this.height * this.width;

}

}

}

// Expression; the class is anonymous but assigned to a variable

const Rectangle = class {

constructor(height, width) {

this.height = height;

this.width = width;

}

};

// Expression; the class has its own name

const Rectangle = class Rectangle2 {

constructor(height, width) {

this.height = height;

this.width = width;

}

};

const rect = new Rectangle(120, 380); Classes are 'special functions'

- class: the blueprint for the instance object

- Capitalized to differentiate with other functions (but it is in essence, a function object, that includes a constructor function to create objects in its image)

- instance: an intance of that class blueprint, created with the

constructorfunction constructor(): a function that instantiates - as in, creates and initializes - an object based on the class- must be called with the

newkeyword

- must be called with the

thiskeyword: refers to the instance object itself. any changes tothisproperties are changes just to that specific instance- method: a function defined within a function

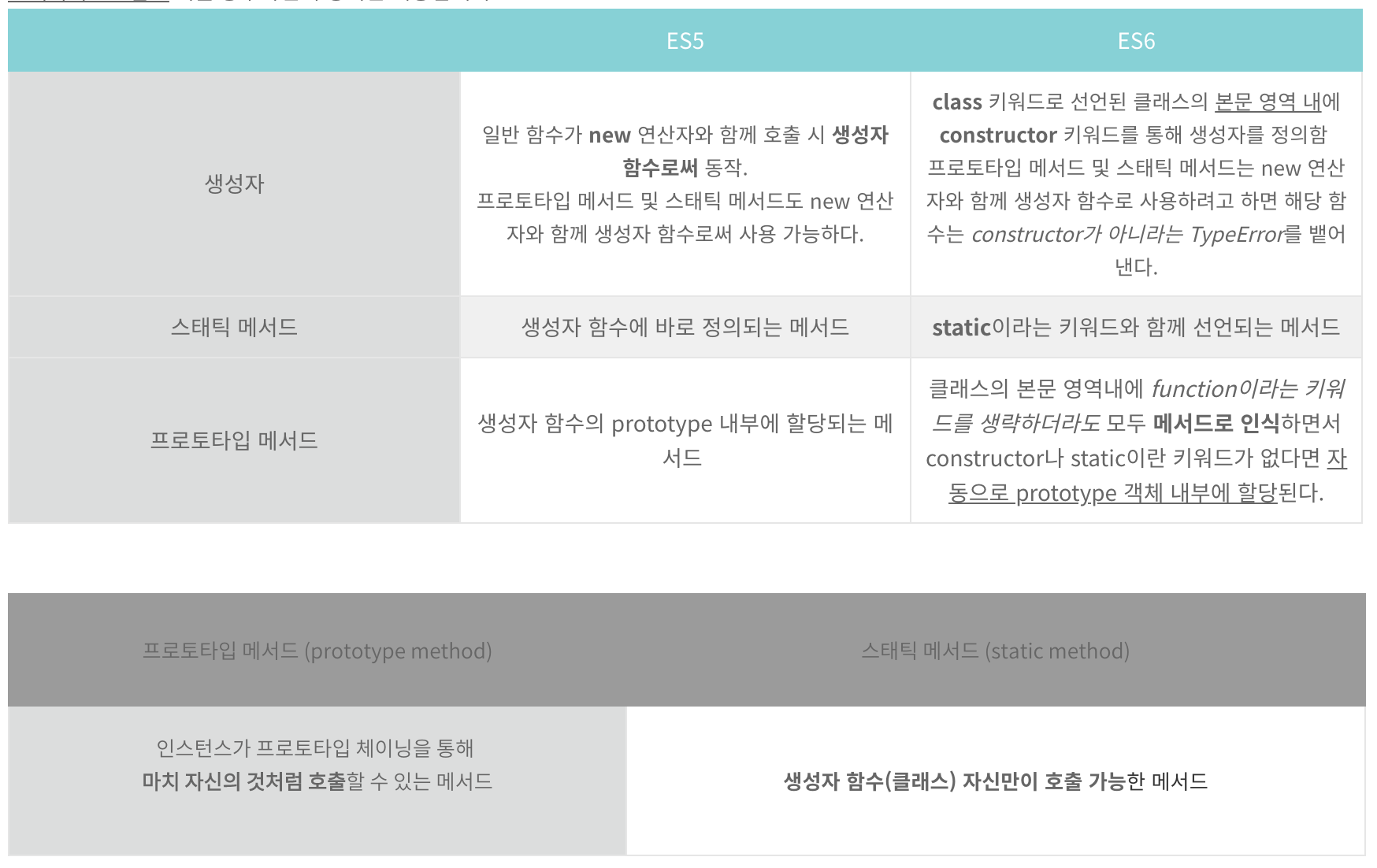

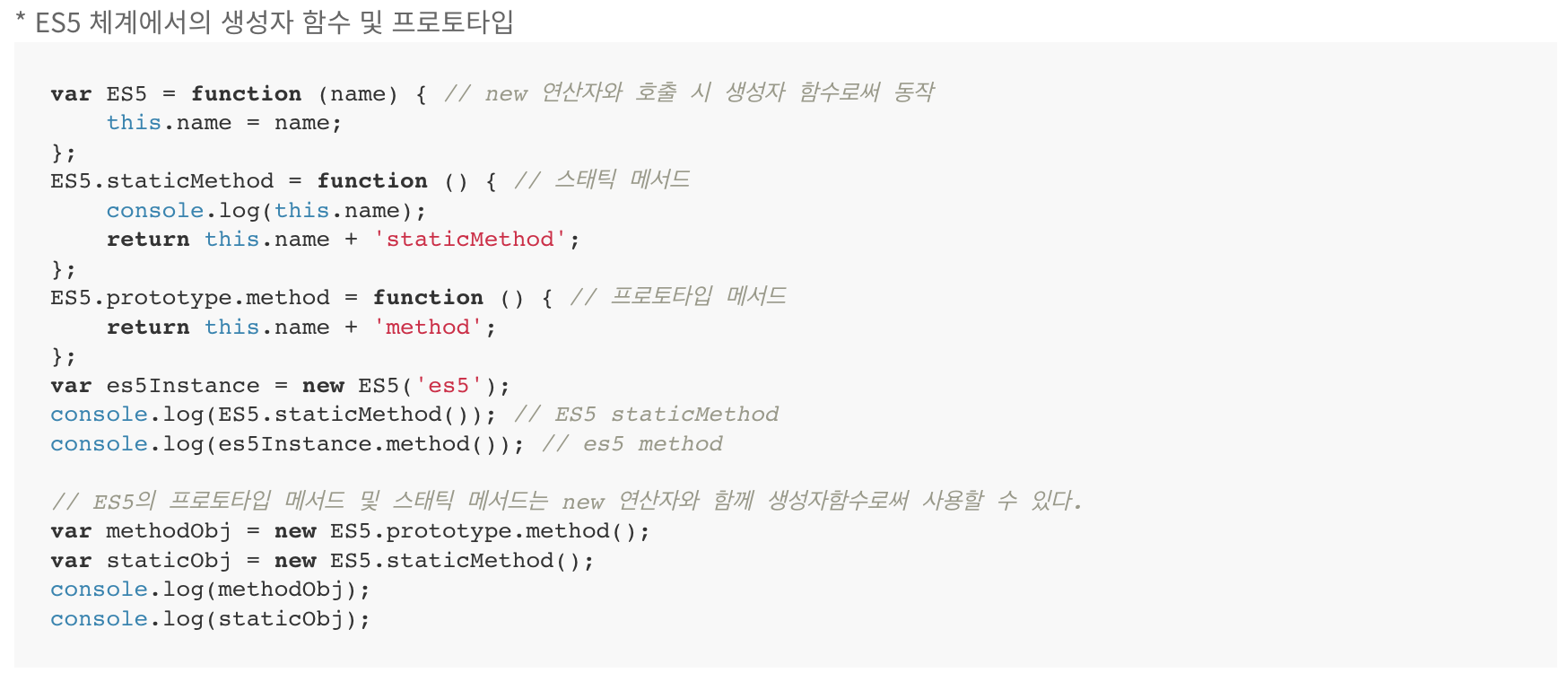

ES5 vs. ES6

ES6 syntax obscures the prototype inheritance model... for better or worse. Below are excerpts from the Core Javascript book, which someone neatly organized into a table and examples here:

Things to keep in mind..

TDZ (Temporal Dead Zone)

Class declarations have the same temporal dead zone restrictions as let or const and behave as if they are not hoisted. (mdh)

Unlike function declarations that are hoisted, this means it will throw a reference error if you try to invoke the class name and constructor function before it has been declared.

Object literal vs constructor

If you create an object using object literals, that object is a singleton, and changes made to that singular object affects that object across the entire script. Objects defined with a function constructor lets us create multiple instances of that object. Changes made to one instance object will not affect the others.

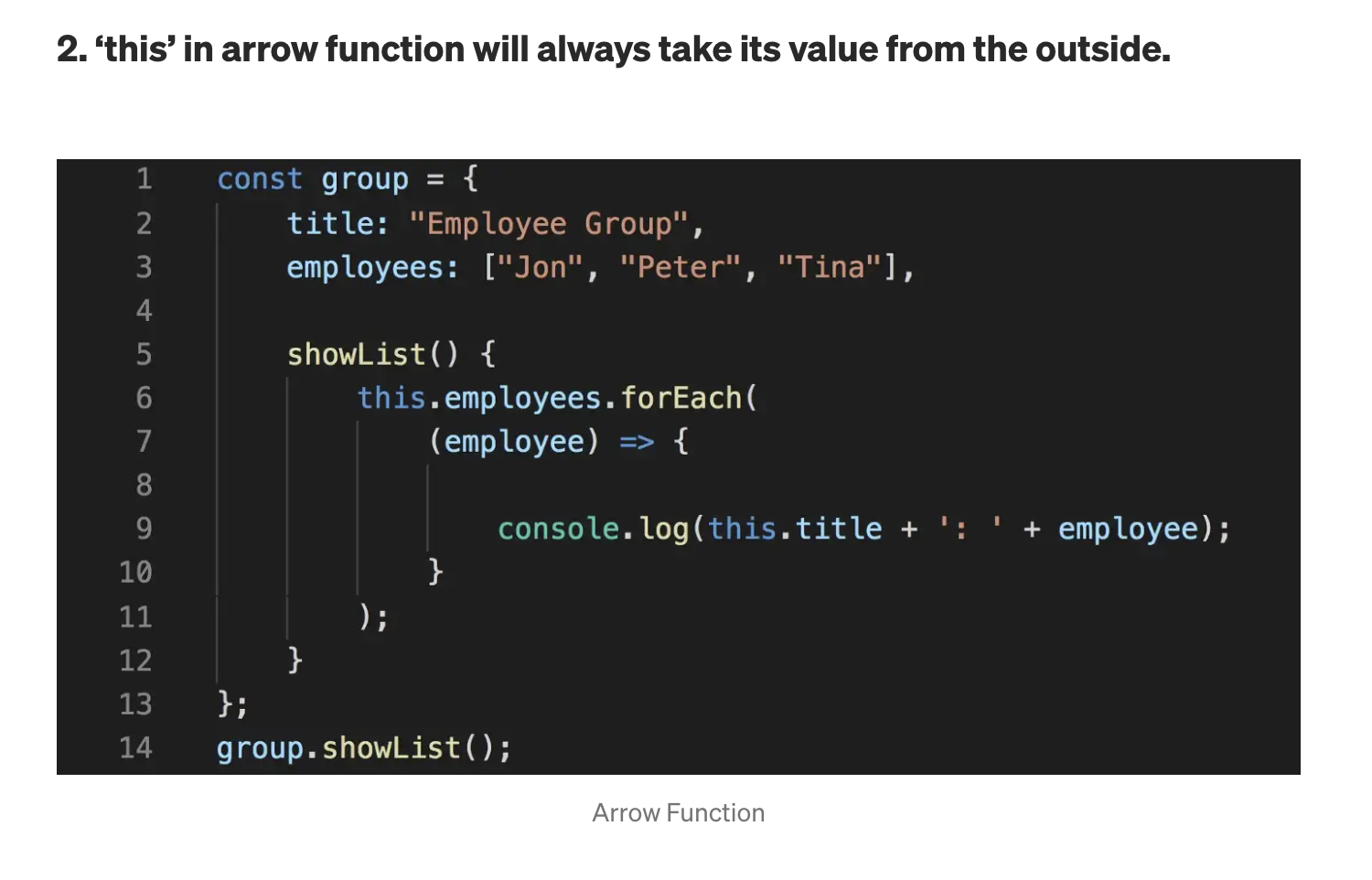

Do not use arrow functions in a method

Especially if it includes this.. it will not bind this to the instantiated object itself, but instead inherits one from its parent scope (lexical scoping).

If you purposefully want this to refer to its parent scope, it could also become handy.

Object Instantiation Methods

To dig into more, later..

References

Object Literal vs. Constructor in Javascript