In the previous post, The very first kind of logical clock - Lamport clock - was covered.

In this post, vector clock follows.

Recap: Lamport clock and causality

If A -> B, then Lc(A) < Lc(B)

But then,

Lc(A) < Lc(B), it doesn't mean that A -> B

Here you can see that what we need to establish causal relationship between two events is something that offers the following property

If A -> B, then Lc(A) < Lc(B)

If Lc(A) < Lc(B), then A -> B

Simply denoted, we want to achieve the following

A -> B <=> Lc(A) < Lc(B)

Vector clocks

Vector clock is the first logical clock that is consistent with AND characterizes casuality.

Unlike Lamport clock that is being an single integer, Vector clock takes on the vector of integers(or some kine of sequence of integers).

How it works

-

Every process maintains a vector of integers initialized to 0, one for each process. If there are three processes, it'll start with

[0,0,0]. To put it another way, if we have[13,0,0], the process with13has seen 13 events whereas the rest of the processes has seen zero. -

On every event, a process increments its own position in its vector clock. Events here, include its own internal event.

-

When sending a message, each process includes its current clock after incrementing its own position)

-

When receiving a message, each process updates its vector clock to the max of the received Vector clock and its own(after incrementing)

How do we get a max? - Pointwise maximum

We get the max as follows:

max([1,12,4], [7,0,2]) == [7,12,4]

But then, how do we define the following? I mean, what would "less than" even meen?

A -> B <=>

Vc(A) < Vc(B)

When the following is true, we say Vc(A) < Vc(B).

1)

Vc(A)i <= Vc(B)ifor all i

2)Vc(A) != Vc(B)

So, if Vc(A) = [2,2,0], and Vc(B) = [3,2,0] then Vc(A) < Vc(B).

What about the following two?

Vc(A) = [2,2,0]Vc(B) = [1,2,3]

-> We found concurrent case

Visual representation

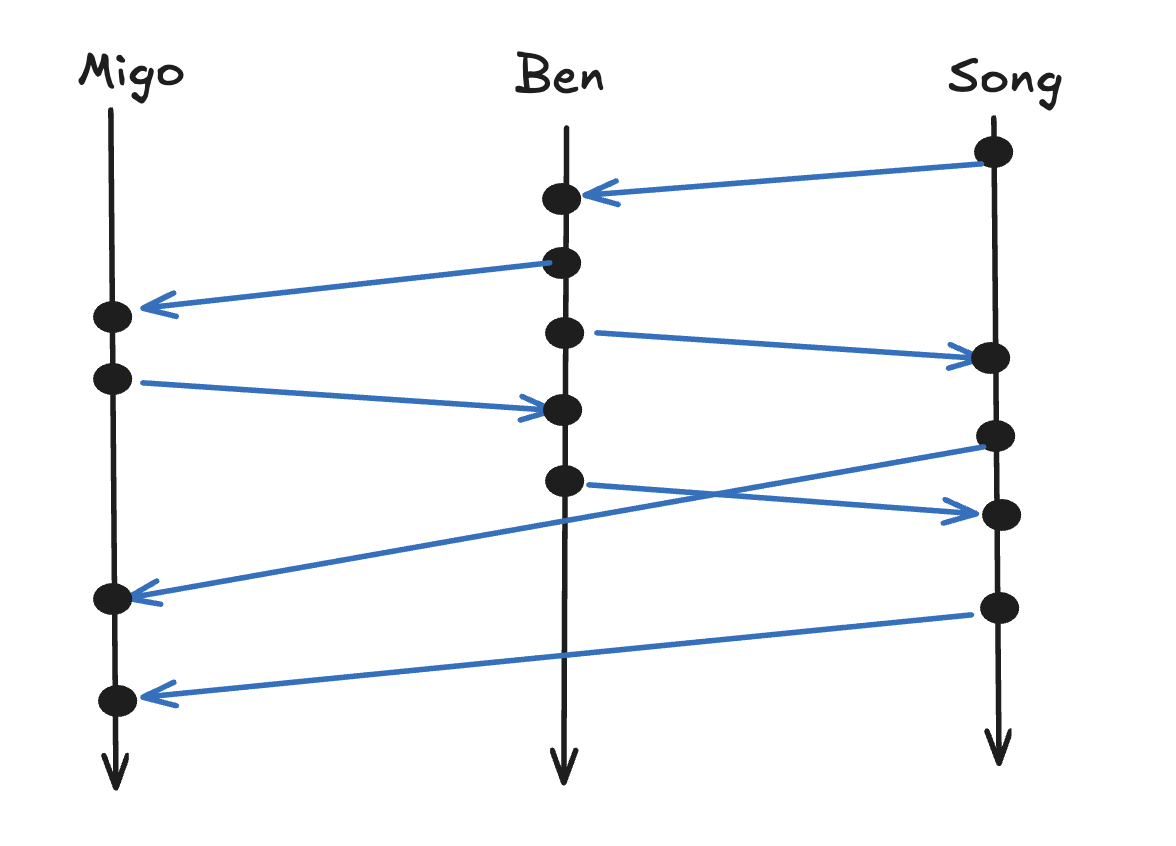

Look at the following and take some time to think of vector clock representation.

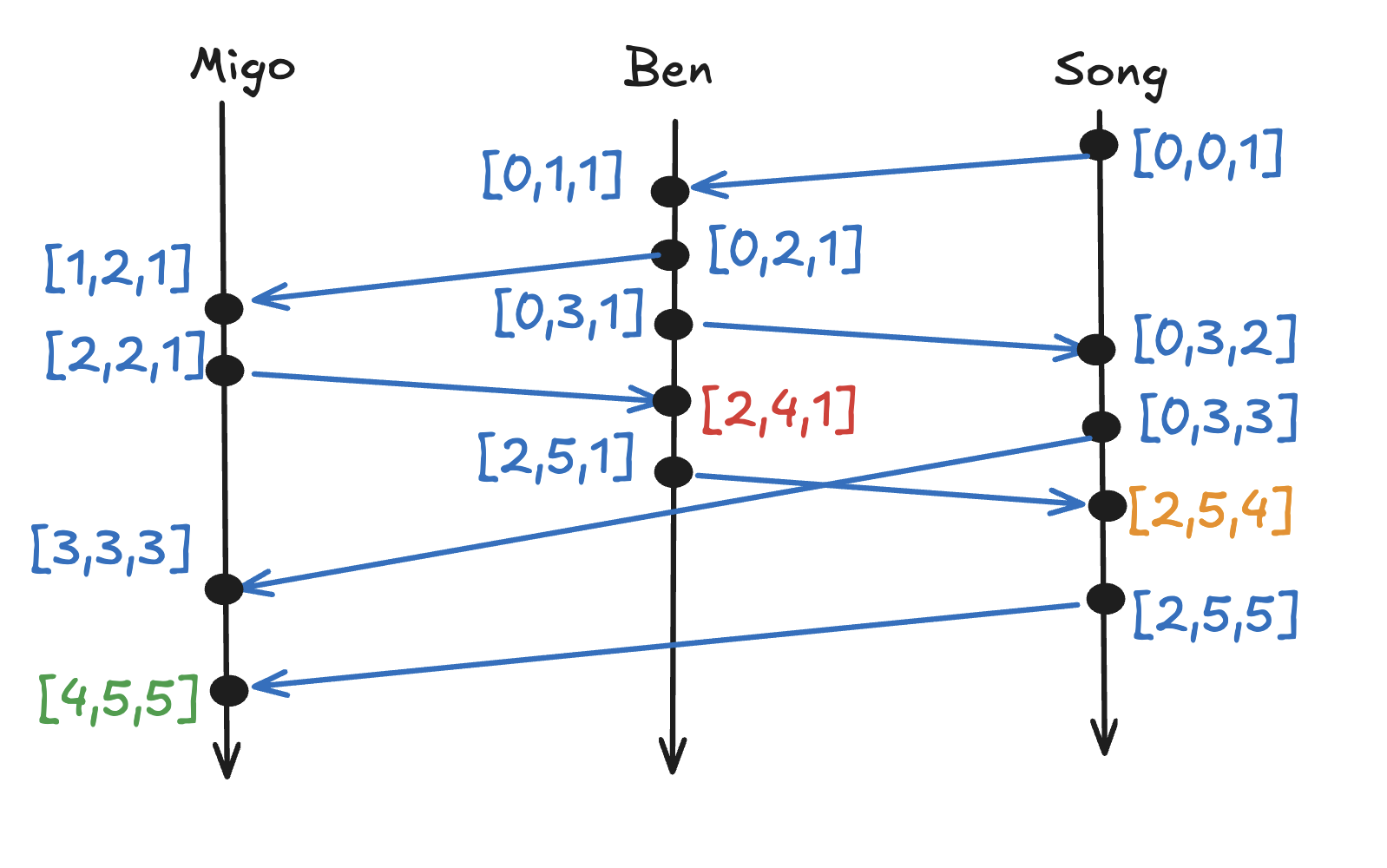

Now, if you draw and apply pointwise maximum, it will look like this:

Here, let's take vector clock in red [2,4,1], for example. It has all the causal history of the following

[0,0,1][0,1,1][0,2,1][0,3,1][1,2,1][2,2,1]

Because we can REACH the [2,4,1] from them(remember casuality was about graph reachability in space time.

Let's then compare [2,4,1] with [0,3,2]. These events are independent. Why is it? Because you cannot tell which one is bigger applying pointwise maximum.

And so is [0,3,3] with [2,4,1].

To put it in another way, these are concurrent, and it's okay to max them out - THIS is really great in that we take somewhat complicate notion of causality and we boil down to just comparing numbers in vectors.

Assumptions

How do we know the order of process in vector clock?

All the processes have to agree an order for the processes in the vector clock - we need to know this information ahead of time. You may want to use graphical order with IP address or the like.

What if we don't know how many processes are there?

And it turns out, Vector clock works only if you have this fixed, ahead of time knowledge of how many processes are there in the system.

And this is one of the reasons why tracking causality by Vector clock can be problematic.