Device Tree in Android SBC Projects: A Practical Engineer’s Guide

Device Tree in Android SBC Projects: A Practical Engineer’s Guide

When Android runs on an ARM-based single-board computer, the kernel does not magically understand the hardware it is sitting on. Unlike PCs with standardized discovery mechanisms, embedded boards are highly customized. The component that fills this gap is the Device Tree. In Android SBC development, understanding how the Device Tree works is often the difference between a stable product and one that fails unpredictably in the field.

This article takes a practical look at the role of the Device Tree (DTB) in Android-based SBCs, focusing on how it is used in real projects rather than theoretical definitions.

Why Android on SBCs Depends on Device Tree

On embedded platforms, the Linux kernel is designed to be hardware-agnostic. It does not hardcode assumptions about displays, power rails, or peripherals. Instead, it relies on a structured hardware description passed in at boot time.

That description is the Device Tree.

For Android SBCs, this is especially important because:

- Boards often differ even when using the same SoC

- Displays, touch panels, and cameras are frequently customized

- Power sequencing is tightly coupled to hardware layout

- Long-term stability matters more than quick bring-up

Without a correct Device Tree, Android may boot, but devices may behave inconsistently or fail after prolonged use.

What a Device Tree Actually Contains

A Device Tree describes hardware, not behavior. It does not contain driver logic. Instead, it provides the data drivers need in order to work correctly.

Typical information defined in a Device Tree includes:

- CPU cores and memory layout

- Buses such as I2C, SPI, and PCIe

- GPIO assignments and pin multiplexing

- Interrupt routing

- Clock sources and frequencies

- Voltage regulators and power dependencies

- Display panels and interface timing

- Peripheral enable and reset signals

This information reflects the board schematic much more closely than application code ever will.

DTS, DTSI, and DTB Explained Simply

Engineers usually work with two types of source files:

-

DTS files

Board-specific descriptions. These represent one concrete SBC design. -

DTSI files

Shared include files, often describing the SoC or common subsystems.

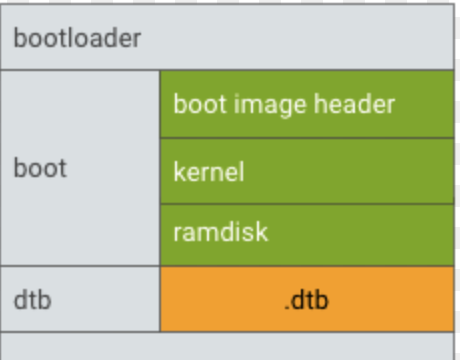

During the build process, these text files are compiled into a binary Device Tree Blob (DTB). The DTB is what the bootloader actually passes to the kernel.

In Android projects, a single kernel may support multiple boards, each with its own DTB.

Where the Device Tree Fits in the Android Boot Flow

A simplified Android boot sequence on an SBC looks like this:

- Boot ROM initializes minimal hardware

- Bootloader configures memory and loads images

- Kernel and DTB are loaded together

- Kernel initializes drivers based on the DTB

- Android userspace starts after kernel initialization

If the DTB is missing, outdated, or mismatched, drivers may not initialize correctly. The system might still boot, but subtle issues often appear later, such as missing touch input or unstable networking.

Driver Initialization and the Device Tree

Kernel drivers do not probe hardware blindly. Instead, they wait for matching Device Tree nodes. Each node includes a compatible string that links it to a specific driver.

Once matched, the driver reads configuration data from the node:

- Register addresses

- Interrupt numbers

- GPIO polarity

- Power supply references

- Timing parameters

If any of these values are wrong, the driver may load but behave incorrectly, which is often harder to debug than a complete failure.

Areas Where DTB Errors Commonly Appear

Display and Touch Integration

Displays are one of the most sensitive subsystems in Android SBCs. A typical setup includes:

- Display controller configuration

- Panel timing parameters

- Backlight control

- Touch controller integration

Small mistakes in timing or power control can cause issues such as flickering, delayed startup, or panels that only work after reboot.

Power Management

Regulators and power rails must be defined accurately. Many peripherals depend on correct sequencing. If a device is powered too early or too late, it may fail silently.

Common problems include:

- Missing regulator references

- Incorrect voltage definitions

- Insufficient startup delays

Pin Multiplexing

SoC pins often support multiple functions. The Device Tree selects which function is active. A single incorrect pinmux setting can disable an entire interface.

Managing DTB in Production Systems

In production environments, consistency is critical. Kernel and DTB versions must remain aligned.

Best practices include:

- Version-controlling DTS files alongside kernel sources

- Rebuilding DTB whenever kernel drivers change

- Avoiding manual DTB edits on deployed systems

- Testing DTB changes under real operating conditions

Updating Android without updating the DTB is a common source of regression.

Debugging Device Tree Issues

Experienced developers rarely rely on guesswork. Typical debugging steps include:

- Inspecting

/proc/device-treeon a running system - Reviewing kernel boot logs for probe failures

- Comparing working and non-working DTBs

- Enabling verbose driver logging during bring-up

These steps often reveal misconfigured nodes quickly.

Device Tree and Android HAL Stability

Android HAL layers assume that kernel drivers are present and functional. If a device never appears at the kernel level, Android services may fail in ways that look unrelated.

A reliable approach is:

1. Validate hardware at the Linux kernel level

2. Confirm driver stability under load

3. Integrate Android HAL and framework layers afterward

This separation avoids chasing Android-side issues caused by DT mistakes.

Conclusion

In Android SBC development, the Device Tree is not a secondary detail. It is the foundation that defines how hardware and software interact. A clean, accurate Device Tree enables stable drivers, predictable behavior, and long-term reliability.

Teams that treat the DTB as a first-class component—maintained, reviewed, and tested like any other critical code—tend to ship products that survive real-world conditions. Those that do not often spend months debugging problems that originate from a few incorrect lines in a DTS file.