Pipelining

- Maintaining Stage Sequence

- IF, ID, EX, MEM, WB. (But to prevent overwritting issue, we should execute reversely)

- Independence Between Stages

- Each stage can operate concurrently without interference.

- Each stage writes its output to a latch, and the next stage reads from that.

- Instruction overlapping

- Instruction 1’s ID and next instruction’s IF are executed in same cycle.**

1. Maintaining Stage Sequence

Part 1. My Implementation

In the development of the five-stage pipelined MIPS emulator, the primary focus was to maintain the integrity of the stage sequence, namely: Instruction Fetch (IF), Instruction Decode (ID), Execute (EX), Memory Access (MEM), and Write Back (WB).

for i in range(len(self.stages) - 1, -1, -1):To address the issue of overwriting and ensure smooth transitions between stages, the emulator was designed to process stages in reverse order. This approach ensures that data dependencies and stage outputs are properly managed, preventing conflicts and data corruption.

Part 2. QEMU Implementation

QEMU's implementation of instruction execution involves a multi-stage process analogous to a CPU pipeline, though it is not structured in exactly the same way as a physical pipeline.

Instead, QEMU focuses on translating guest instructions into host instructions that can be executed directly by the host CPU.

Q1. How QEMU divided stages?\

A. IF+ID to TB (Translation Block) Execution, EX+MEM to Instruction Translation.

Q2. What is TB?\

A. QEMU groups a sequence of guest instructions into a Translation Block (TB).**

Each TB is a unit of execution containing several instructions that are translated together. The core execution loop in QEMU fetches and executes these TBs, akin to the IF (Instruction Fetch) and ID (Instruction Decode) stages in a classic CPU pipeline.

tb = tb_lookup(cpu, pc, cs_base, flags, cflags);

if (tb == NULL) {

mmap_lock();

tb = tb_gen_code(cpu, pc, cs_base, flags, cflags);

mmap_unlock();

}‘tb_lookup’ searches for an existing TB in the cache based on the current PC, cs_base, flags, and cflags. If no cached TB is found, ‘tb_gen_code’ generates a new TB. This involves translating a block of guest instructions into host instructions.

/*

We add the TB in the virtual pc hash table for the fast lookup

*/

h = tb_jmp_cache_hash_func(pc);

jc = cpu->tb_jmp_cache;

jc->array[h].pc = pc;

qatomic_set(&jc->array[h].tb, tb);https://github.com/qemu/qemu/blob/dec9742cbc59415a8b83e382e7ae36395394e4bd/accel/tcg/cpu-exec.c

(from cpu_exec_loop(CPUState *cpu, SyncCloks *sc))

The newly generated TB is added to a jump cache (cpu->tb_jmp_cache). This cache uses a hash function (tb_jmp_cache_hash_func) to map PCs to their corresponding TBs for fast lookup in future executions.

Q3. Why QEMU used TB?\

A. For performance optimization. More specifically, dynamic binary translation and caching.

- QEMU Converts guest machine instructions into host machine instructions, in other words, provides dynamic binary translation. Also, instead of translating instructions one at a time, QEMU translates blocks of instructions. By caching the TBs, QEMU can bypass this translation step on subsequent executions of the same code block, thereby speeding up execution.

- QEMU uses the TCG(Tiny Code Generator) to translate guest instructions into intermediate code, which is then translated into host machine code. This process involves stages similar to the EX (Execute) and MEM (Memory Access) stages. TCG performs the translation in stages, starting from the guest instruction set to intermediate representation and finally to host instructions.

- Finally, QEMU uses block chaining to link multiple TB. Block chaining involves linking together multiple stages or tasks in the pipeline so that the output of one stage is directly connected to the input of the next stage, forming a chain. This allows data to flow seamlessly from one stage to the next without the need for intermediate storage or context switching.

- The main idea behind block chaining is to reduce the latency introduced by switching between stages. Instead of completing one task in a stage, storing the result temporarily, and then transferring it to the next stage, block chaining enables the result to be transferred directly from one stage to the next as soon as it is available. This eliminates unnecessary delays and improves overall throughput.

Part 3. My code improved by referring to QEMU

I think adopting TB concept is not appropriate for my codework.

If MIPS is the host, then there may not be a need to introduce the concept of Translation Blocks (TBs). TBs are typically used in virtualization or emulation software to efficiently manage the translation of instructions between the host and guest architectures. If the host system directly supports the MIPS architecture, such translation processes may not be necessary.

Therefore, without introducing the concept of TBs, it is possible to directly execute MIPS instructions and return results. However, using the TB concept can optimize performance in certain situations, so it may be worth considering for performance improvement if needed.

But using block chaining may helpful. So, I decided to add code below.

- inserted code

# Pre-load next instruction (block chaining logic)

next_index = shred.pc + self.pipeline_depth - 1- full code

# Move instructions to the next stage

for i in range(len(self.stages) - 1, 0, -1):

if not self.pipeline[i]:

self.pipeline[i] = self.pipeline[i - 1]

self.pipeline[i - 1] = None

# Fetch new instruction

if shred.pc < len(instruction_memory) and not self.pipeline[0]:

self.pipeline[0] = self.if_stage(shred, log)

# Pre-load next instruction (block chaining logic)

next_index = shred.pc + self.pipeline_depth - 1

if next_index < len(instruction_memory):

self.pipeline[-1] = instruction_memory[next_index]In the context of the provided code, block chaining can be implemented by loading the next instruction into the pipeline's last stage immediately after loading the current instruction into the first stage. This ensures that the next instruction is ready to be executed as soon as the current instruction completes, without waiting for additional cycles or context switches.

By leveraging block chaining, the pipeline can maintain a continuous flow of instructions, maximizing throughput and minimizing idle time. This ultimately leads to improved performance and efficiency in executing a sequence of instructions.

2. Independence Between Stages

Part 1. My Implementation

class Latch:

def __init__(self):

self.pc = None

self.instruction = Instruction()

def flush(self):

self.pc = None

self.instruction = NoneTo achieve concurrent operation of all pipeline stages without interference, each stage's output written to a latch, which the subsequent stage reads from. This decoupling allows each stage to operate independently, ensuring that the execution of one stage does not affect the others.

Part 2. QEMU Implementation

In QEMU, the Transfer Block (TB) mechanism is used.

When a TB is generated, it encapsulates a sequence of translated instructions along with metadata such as the source program counter (PC) and flags. During execution, the TB is traversed through various stages, each representing a step in the emulation process. Data is transferred between these stages primarily through the TB structure itself, which carries the necessary information for each stage to perform its tasks. This allows for seamless coordination and execution of translated code within QEMU's emulation pipeline.

TranslationBlock *tb_gen_code(CPUState *cpu,

vaddr pc, uint64_t cs_base,

uint32_t flags, int cflags)

{

CPUArchState *env = cpu_env(cpu);

TranslationBlock *tb, *existing_tb;

...

phys_pc = get_page_addr_code_hostp(env, pc, &host_pc);

...

tb = tb_alloc(pc, cs_base, flags, cflags);

...

tb->cs_base = cs_base;

tb->flags = flags;

tb->cflags = cflags;3. Instruction Overlapping

Part 1. My Implementation

class Pipeline:

def __init__(self):

self.stages = ["IF", "ID", "EX", "MEM", "WB"]

self.pipeline = deque([None] * 5) # Initialize pipeline with 5 stages, all empty

self.clock = 0 # Initialize clock cycle counterDeque is utilized in the code to manage the pipeline stages efficiently. By representing each stage as an element in the deque, it allows for easy insertion and removal of instructions at different pipeline stages. This data structure facilitates overlapping execution by enabling the movement of instructions through the pipeline in a streamlined manner. With deque, instructions can be added to the front of the pipeline while older instructions progress through subsequent stages, maintaining the overlap of instruction execution. Overall, deque enhances the management and processing of instructions within the pipeline, contributing to improved performance and efficiency.

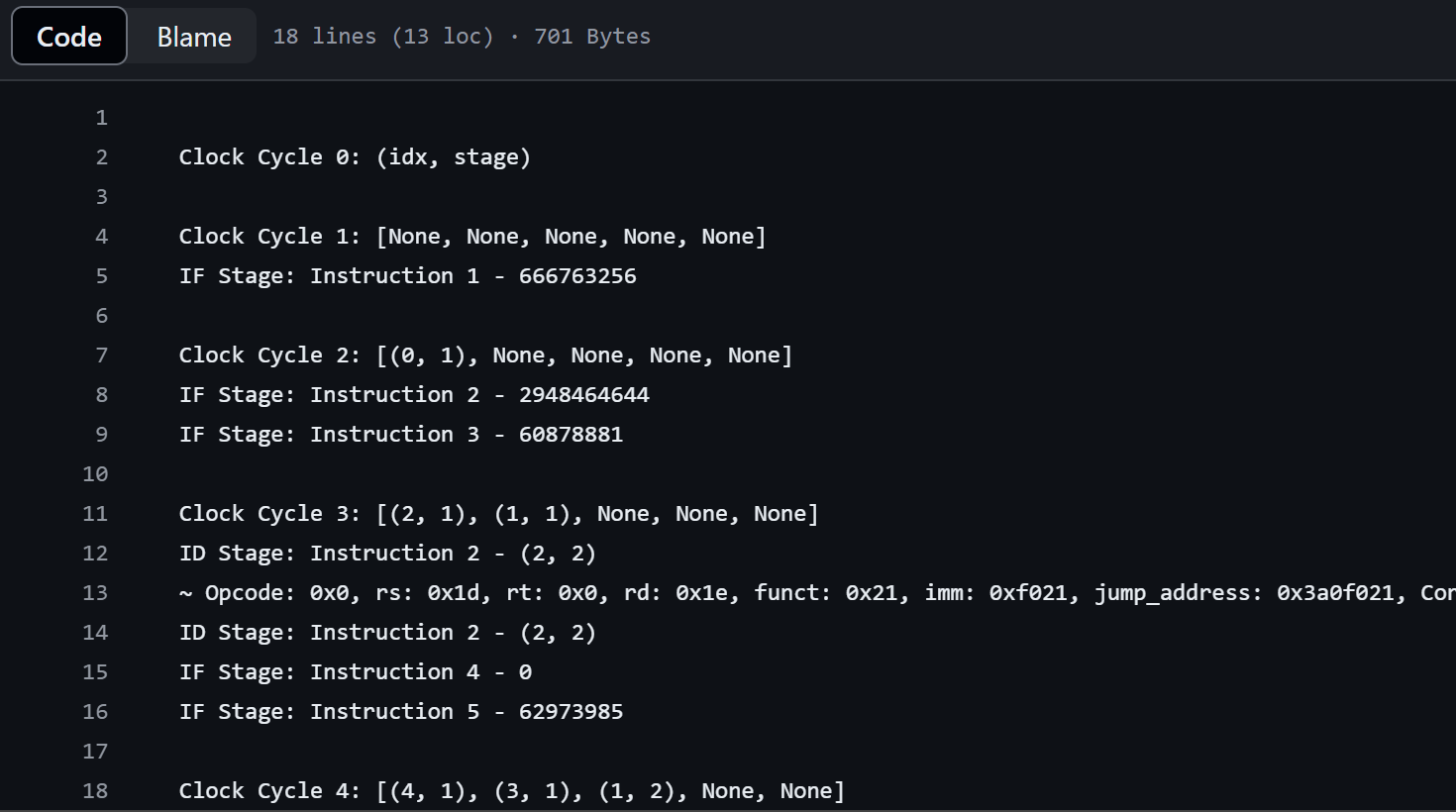

def run(self, shred):

instruction_memory = shred.instruction_memory

with open("logs/pipelined.txt", "w") as log:

log.write(f"\nClock Cycle {self.clock}: (idx, stage)\n")

while shred.pc <= len(instruction_memory) or any(self.pipeline):

self.clock += 1

log.write(f"\nClock Cycle {self.clock}: {list(self.pipeline)}\n")

# Process pipeline stages in reverse order to prevent overwriting

for i in range(len(self.stages) - 1, -1, -1):

if shred.pc >= len(instruction_memory):

return

if self.pipeline[i]:

if self.pipeline[i].stage == len(self.stages):

self.pipeline[i] = None # Instruction is done

else:

self.process_stage(i, shred, log)(Reverse order for preventing overwriting. I already explained in Topic1)

for i in range(len(self.stages) - 1, -1, -1):

if shred.pc >= len(instruction_memory):

return

if self.pipeline[i]:

if self.pipeline[i].stage == len(self.stages):

self.pipeline[i] = None # Instruction is done

else:

self.process_stage(i, shred, log)This segment of the code advances instructions to the next pipeline stage by shifting them down the pipeline. It ensures instruction overlapping by allowing new instructions to enter the pipeline when the first stage is vacant. This mechanism enables efficient pipelining, where multiple instructions can be processed simultaneously at different stages, enhancing overall throughput. The "if not self.pipeline[0]" condition checks if the first stage is empty, indicating space for a new instruction, facilitating overlapping execution.