Challenges

A1. Create a blockchain network with an interface supporting transaction timing constraints and flexible block generation for accommodating more transactions within a single block time.

- There is no interface to express and utilize the deadline of each transaction.

(gas is not an answer.) - Make nodes can send each transaction to put as input the expected deadline of the transaction - Increasing the rate of generating blocks itself cannot guarantee timely execution and incurs space inefficiency. (idle blocks can be accumulated.)

- Extend the target network to provide the flexibility of making zero to multiple blocks at a single block time.

A2. Develop novel scheduling principles specialized for the blockchain network so as to guarantee the timely execution of periodic/sporadic transactions without wasting the blockchain network resources.

- The timeline of the transaction request of a transaction-generating node is different from that of a block-generating node.

- Translate a periodic/sporadic request of a transaction-generating node, into a periodic/sporadic arrival on a block-generating node.

- Derive a condition of the modeled transaction load.

- Each transaction cannot be split to be included in more than one block.

- Develop a lazy deadline-based scheduling policy and its condition

Contributions

- We raise and address two issues to achieve timing guarantees for blockchain transactions, which is the first attempt.

- We modify the existing blockchain network enabling deadline-based transaction selection and extend it to provide the flexibility of the number of generated blocks at a single block time.

- We develop novel scheduling principles that can guarantee the timely execution of periodic/sporadic transactions, which is the first achievement.

- We develop advanced scheduling methodologies that reduce the number of generated blocks without compromising timing guarantees of transactions.

- We implement the proposed network architecture and scheduling principles in a real blockchain, and evaluate their performance.

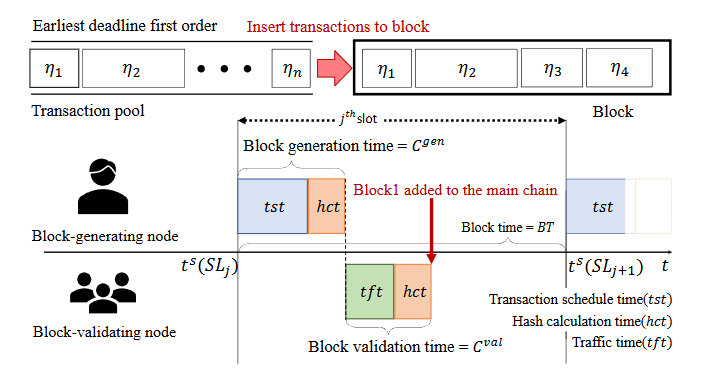

RT-Blockchain

- A single block is generated and connected to the main blockchain

at regular intervals (slots) - Each of whose duration is same and called block time ()

- All transactions entering the system are stored in the transaction pool, and they are ordered based on their respective deadlines, with the earliest deadline transactions given priority.

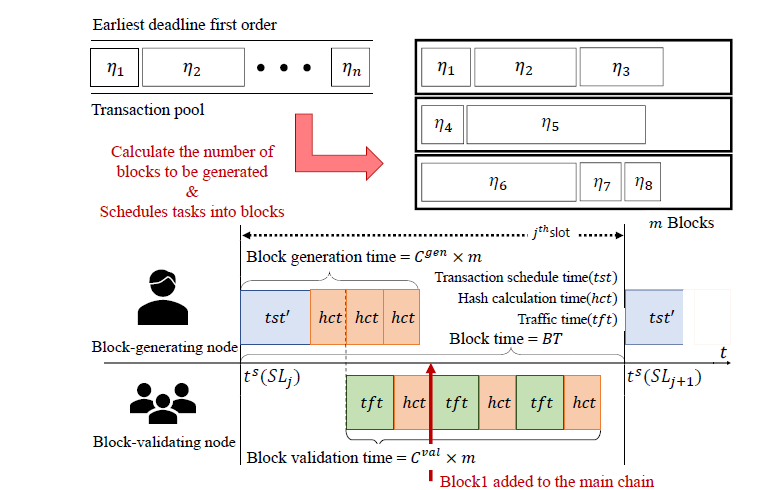

RT-Blockchain: Node's POV

Block Generation Time

- Select node to create the block.

- The selected block-generating node stops accepting additional

transactions into its pool. - Starts selecting transactions to be included and then including them in the block.

- Also calculates block hash for ensuring the integrity and sequential order of the blocks in the blockchain.

Block Validation Time

- Validators independently validate the transactions and verify the

block hash. - This process, starting from when the block is distributed to when

it is added to the main chain, is defined asblock validation time.

RT-Blockchain: User's POV

Block Generation Time

- The duration from the sender to the pool, representing the transaction's time within the network, is referred to as

traffic time() - denote the time instant at which starts.

transaction schedule time: A block is filled with scheduled transactions ()- Hash calculation time ()

- Block generation time

Block Validation Time

- The generated block is distributed throughout the network and reaches the local machines of each validator ()

- The validating nodes run hash calculations on the given block to

check the validity() - User’s transaction request can finish its execution no later than

Timely Transactions on RT-Blockchain

Definition 1.

A periodic/sporadic user-level blockchain transaction task > , : the inter-arrival time, : the relative deadline, : the maximum transaction size.A user-level blockchain transaction task generates a series of transaction jobs, the of which is denoted by .

The release times of ’s two consecutive jobs and are separated by at least

Once a job is released at , its transaction whose size is at most should be completed no later than

Definition 2.

A periodic/sporadic user-level blockchain transaction task set is said to be schedulable, if there is no single job deadline miss for every legal job series generated by .

Now we can state our goal as follows.

Problem Statement:

We develop a deadline-based scheduling algorithm and a schedulability condition for , which is scheduled by the scheduling algorithm on a RT-blockchain system, such thatG1. is schedulable if satisfies the schedulability condition (achieving timing guarantees).

Achieving G1 in the problem statement is totally different from the case for the traditional real-time periodic/sporadic task set executed on a computing platform due to the following challenges:

- The timeline of each user’s transaction request is different from that of block generation.

- Each transaction cannot be split to be included in more than one block, which may yield an arbitrarily small utilization of each block under priority-based approaches.

To address C1 first, we need to interpret the release time and the absolute deadline of each user’s transaction job, from the block-generating node’s point of view.

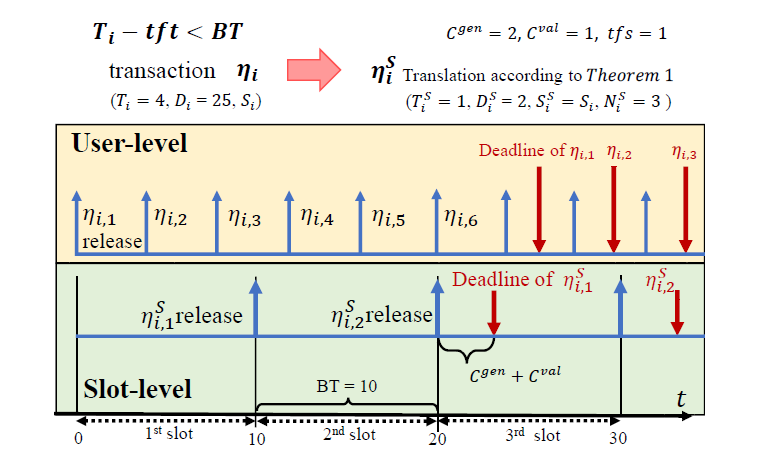

User-level to Slot-level Translation

Definition 3.

A periodic/sporadic slot-level blockchain transaction task

- : the inter-arrival slots

- : the slot-unit relative deadline

- : the maximum transaction size

- : the number of transactions of each job of

The ready-to-be-scheduled time instant for is .

Once a job is ready-to-be-scheduled at , there are transactions whose size is at most .Each of them should be included in any block of , , , or ,

Definition 4.

A periodic/sporadic slot-level blockchain transaction task set is said to 1be schedulable, if there is no single job deadline miss for every legal job series generated by .

We can translate to , without compromising timing constraints of every .

We should consider two cases:

Theorem 1

The schedulability of a periodic/sporadic user-level blockchain transaction task set is schedulable on a RT-blockchain system, if its corresponding periodic/sporadic slot-level blockchain transaction task set is schedulable, where parameters of each is set as follows.

Proof for

The worst case is a job of in block-generating node right after .

If its absolute deadline is no earlier than , it does not miss the deadline.

It's equivalent to .

Therefore, is not smaller than . which is equivalant to Eq. .

Timing Guarantees for RT-Blockchain

Now we can translate the G1 to G1

Problem Statement:

We develop a deadline-based scheduling algorithm and a schedulability condition for , which is scheduled by the scheduling algorithm on a RT-blockchain system, such thatG1. is schedulable if satisfies the schedulability condition (achieving timing guarantees).

Apply (Work-Conserving Earliest Deadline First) for a RT-blockchain system as follows:

Algorithm of for with a single block

- At every beginning of each slot, sort all transactions in the waiting queue by their absolute slot-unit deadlines.

- Then, assign each sorted transaction to the block one by one, until the highest-priority unassigned transaction in the waiting queue cannot be assigned due to the remaining portion of the block is smaller than the size of the highest-priority unassigned transaction.

Definition 5.

Let denote the demand bound function for a slot-level blockchain transition task during consecutive slots (where ), defined by

Definition 6.

Let denote the maximum of the sum of all for divided by the number of consecutive slots , which is defined by

One may think that could be schedulability condition for .

However, this is wrong due to C2: Each transaction cannot be split to be included in more than one block.

Theorem 2

A set of periodic/sporadic slot-level blockchain transaction tasks is schedulable by on a RT-blockchain system, if the following condition holds.

Proof

First, we prove the statement: if the sum of the size of transactions in the waiting queue is larger than , the block can include a set of transaction whose size summation is at least .

Suppose that the statement is wrong, then there exists a job that cannot be included in the block.

But the block has at least amount remaining space.

This violates the

Work-conserving

- Second, suppose that there exists a deadline miss of transaction of at the slot.

- Let () is the largest index of the slot, such that

- is strictly larger than the sum of the size of transactions whose slot-unit absolute deadline is no later than that of the transaction in the block of slot.

- is no larger than that in the block of slot.

The first property implies that there is no job whose release slot index is or smaller, but is not included in any block until the beginning of the slot.

Therefore, is the largest possible sum of the size of transactions whose slot-unit absolute deadline is no later than that of .

Also, by definition, is a lower bound of the sum of the size of transactions whose slot-unit absolute deadline is no later than that of .This contradicts Eq. .

Design of Multi-Block RT-Blockchain

We design an architecture that generates multiple blocks per block time to enhance the scalability of the blockchain system while preventing the generation of empty blocks.

: multi-block RT-blockchain

Unlike traditional blockchain systems, our architecture allows the block-generating node to determine the number of blocks to generate during each block time based on the transactions in the pool.

- : a predefined threshold of the maximum number of generating blocks in each slot.

Design of Multi-Block RT-Blockchain

- The node generating the block first calculates how many blocks will be needed to fit the transaction in the pool

- the node stores transactions sequentially in each block while keeping the bound

We assume that , implying block generation time for a -block RT-blockchain is upper-bounded by .

Also, block validation time is upper-bounded by .

Therefore, any transaction included in one of the m blocks at the jth slot is finished no later than

Timing Guarantees for Multi-Block RT-Blockchain

Theorem 3

The schedulability of a periodic/sporadic user-level block-chain transaction task set is schedulable on a -block blockchain system,

If its corresponding periodic/sporadic slot-level block-chain transaction task set is schedulable, where of each is set to Eq. and other parameters are set to Eqs. , and in Theorem 1.

When it comes to the scheduling algorithm, we also apply , generalized for blocks (instead of a single block) to be supplied.

Algorithm of for with blocks

- At every beginning of each slot (i.e., ), sort all transactions in the waiting queue by their absolute slot-unit deadlines.

- Then, assign each sorted transaction to one of the blocks one by one using the first-fit policy, until the highest-priority unassigned transaction in the waiting queue cannot be assigned to any of the m blocks

Theorem 4

A set of periodic/sporadic slot-level blockchain transaction tasks is schedulable by on a -block blockchain system, if the following condition holds

But if is small, Theorem 4 is pessimistic.

We can improve this as follows.

Theorem 5

A set of periodic/sporadic slot-level blockchain transaction tasks is schedulable by on a -block blockchain system, if the following condition holds

Proof

We only need to prove the case for .

If the sum of the size of transactions in the waiting queue is larger than , the block can include a set of transactions whose size summation is at least without violating the priority of transactionsSuppose that there are at least two blocks, each of which is occupied no larger than 50%,

Then, it immediately contradicts the first-fit policy in .

Therefore, there is at most one block that is occupied no larger than 50%.

Since no schedular can make schedulable if , the resource augmentation bound(?) is

which converges to 2.

Resource Efficiency with Timing Guarantees.

G2. The number of generated blocks is minimized.

We develop a lazy algorithm called as follows, where is a positive rational number less than .

Algorithm of for with blocks

- At every beginning of each slot (i.e., ), sort all transactions in the waiting queue by their absolute slot-unit deadlines.

- Then, assign each sorted transaction to one of the blocks one by one using the first-fit policy, until the sum of for all assigned transactions is no smaller than .

- Let denote the number of blocks occupied by at least one transaction so far.

- We apply for the remaining unassigned transactions as if we have only the blocks instead of

Theorem 6.

A set of periodic/sporadic slot-level blockchain transaction tasks is schedulable by on a -block blockchain system, if Eq. (1 holds.

Proof

If the sum of the size of transactions in the waiting queue is larger than , the block can include a set of transactions whose size summation is at least without violating the priority of transactions.The operation of is exactly the same as that of until the or smaller blocks include a set of earliest-deadline transactions whose size summation is barely no smaller than , the remaining proof is similar to that of Theorem 5.

Implementation

- Turtlecoin, a commercially available and highly extensible blockchain platform.

- PoS (Proof of Stake) Consensus Mechanism

- BT = 12s, BS = 100KB

- 66% of validators should include the block in their main chain.