Deep Learning

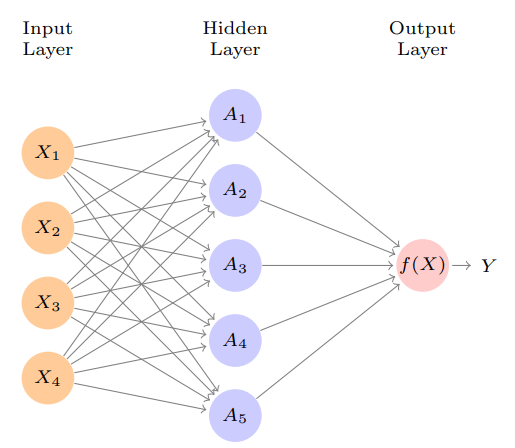

Single Layer Neural Network

- are called the

activationsin thehidden layer - is called the

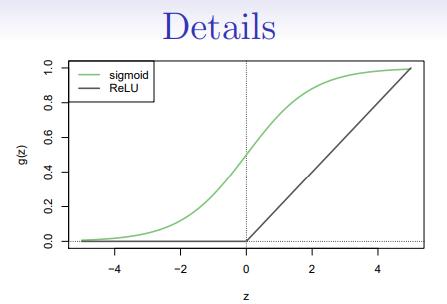

activation function. Popular are thesigmoidandrectified linear, shown in figure - Activation functions in hidden layers are typically

nonlinear, otherwise the model collapses to a linear model - So the activations are like derived features - nonlinear transformations of linear combinations of the features

- The model is fit by minimizing (e.g. for regression)

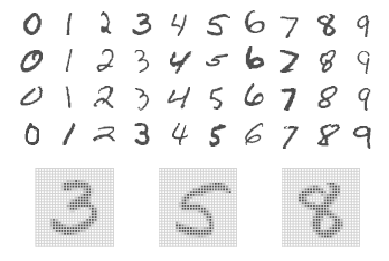

Example : MNIST Digits

- Handwritten digits grayscale images train, test images

- Features are the pixel grayscale values

- Labels are the digit class

- Goal : build a classifier to predict the image class

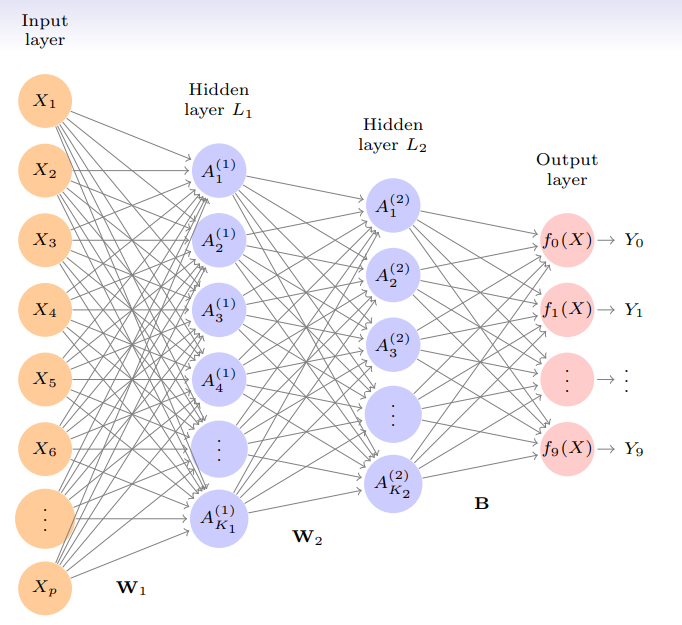

- We build a two-layer network with units at first layer, units at second layer, and units at output layer

- Along with intercepts (called

biases) there are parameters (referred to asweights)

- Let be linear combinations of activations at second layer

- Output activation function encodes the

softmaxfunction - We fit the model by minimizing the negative multinomial log-likelihood (or cross-entropy)

- is if true class for observation is , else - i.e.

one-hot encoded

- Early success for neural networks in the 1990s

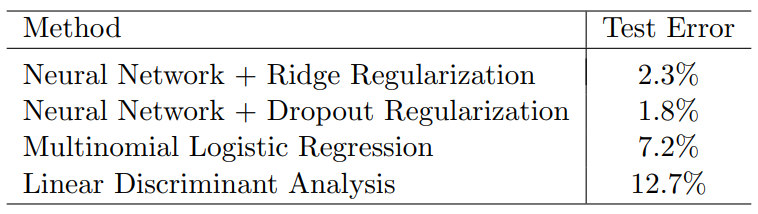

- With so many parameters, regularization is essential

- Some details of regularization and fitting will come later

- Very overworked problem - best reported rates are <

- Human error rate is reported to be aroung

Convolutional Neural Network - CNN

- Major success story for classifying images

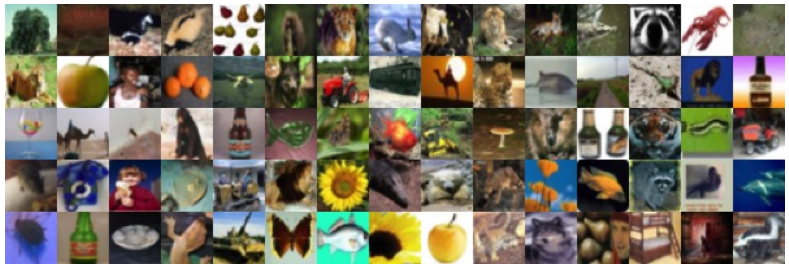

- Shown are samples from

CIFAR100database - color natural images, with classes

- training images, test images

- Each image is a three-dimensional array of

feature map: array of -bit numbers - The last dimension represents the three color channels for red, green and blue

- The

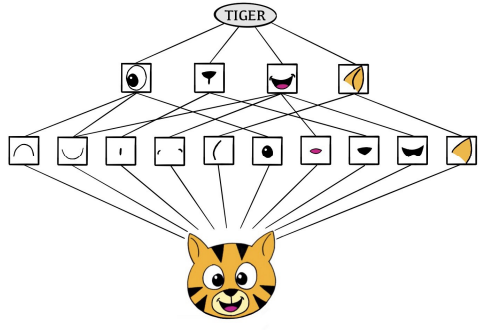

CNNbuilds up an image in a hierarchical fashion - Edges and shapes are recognized and pieced together to form more complex shapes, eventually assembling the target image

- This hierarchical construction is achieved using

convolutionandpoolinglayers

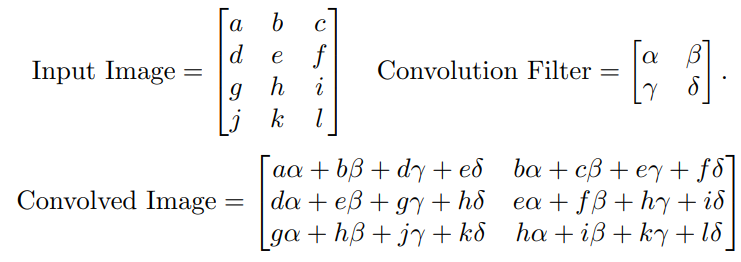

Convolution Filter

- The filter is itself an image, and represents a samll shape, edge etc.

- We slide it around the input image, scoring for matches

- The scoring is done via

dot-products, illustrated above - If the subimage of the input image is similar to the filter, the score is high, otherwise low

- The filters are

learnedduring training

- The idea of convolution with a filter is to find common patterns that occur in differnet parts of the image

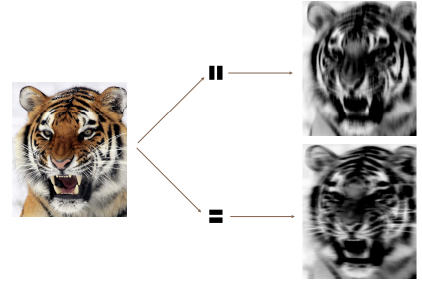

- The two filters shown here highlight vertical and horizontal stripes

The resultof the convolution is anew feature map- Since images have three colors channels, the filter does as well : one filter per channel, and dot-products are summed

- The weights in the filters are

learnedby the network

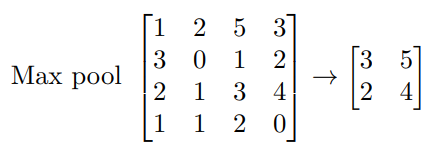

Pooling

- Each non-overlapping block is replaced by its maximum

- This sharpens the feature identification

- Allows for locational invariance

- Reduces the dimension by a factor of - i.e. factor of in each dimension

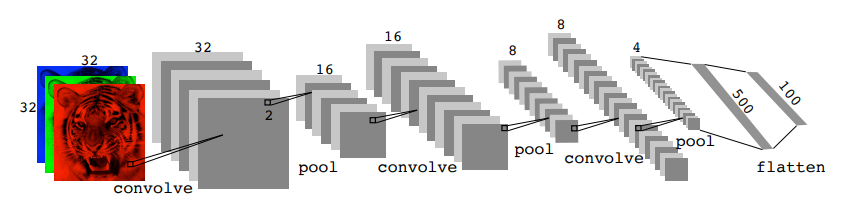

Architecture of a CNN

- Many

convolve+poollayers - Filters are typically small, e.g. each channel

- Each filter creates a new channel in convolution layer

- As pooling reduces size, the number of filters/channels is typically increased

- Number of layers can be very large. E.g.

resnet50trained onimagenet1000-class image data base has layers

Document Classification

Featurization : Bag-of-Words

- Documents have different lengths, and consist of sequences of words

- How do we create features to characterize a document?

- From a dictionary, identify the most frequently occurring words

- Create a binary vector of length for each document, and score a in every position that the corresponding word occurred

- With documents, we now have a

sparsefeature matrix - We compare a

lassologistic regression model to atwo-hidden-layerneural network on the next slide Bag-of-wordsareunigrams- We can instead use

bigrams( occurrences of adjacent word pairs ), and in generalm-grams

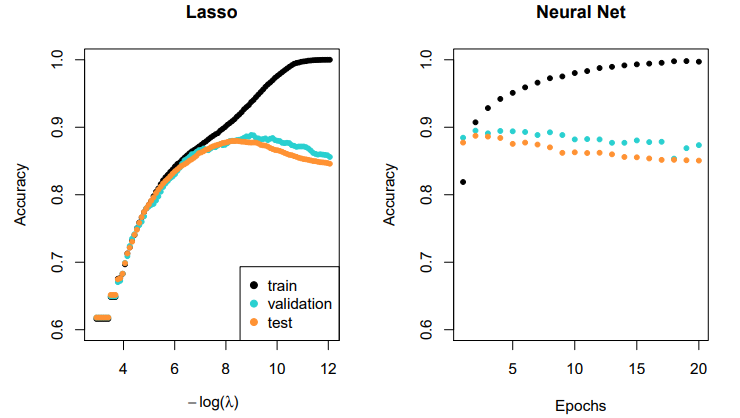

Lasso vs Neural Network

- Simpler

lassologistic regression model works as well as neural network in this case

Recurrent Neural Networks

- Often data arise as sequences :

- Documents are sequences of words, and their relative positions have meaning

- Time-series such as weather data or financial indices

- Recorded speech or music

- Handwriting, such as doctor's notes

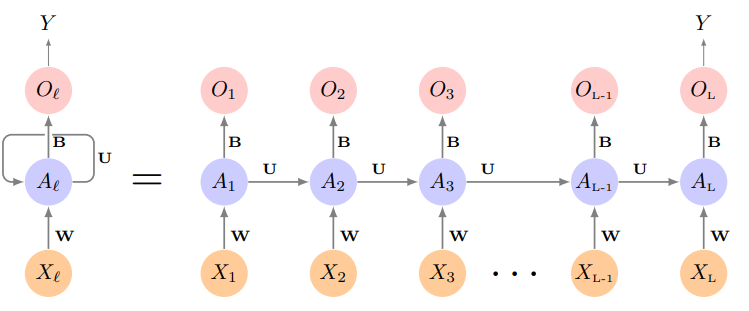

RNNs build models that take into account this sequential nature of the data, and build a memory of the past- The feature for each observation is a

sequenceof vectors - The target is often of the usual kind - e.g. a single variable such as

Sentiment, or a one-hot vector for multiclass - However, can also be a sequence, such as the same document in a differnet language

- The feature for each observation is a

- The hidden layer is a sequence of vectors , receiving as input as well as

- produces an output

- The

sameweights , and are used at each step in the sequence - hence the termrecurrent - The sequence represents an evolving model for the response that is updated as each element is processed

- Suppose has components, and has components

- Then the computation at the th components of hidden unit is

- Often we are concerned only with the prediction at the last unit

- For squared error loss, and sequence / response pairs, we would minimize

RNN and IMDB Reviews

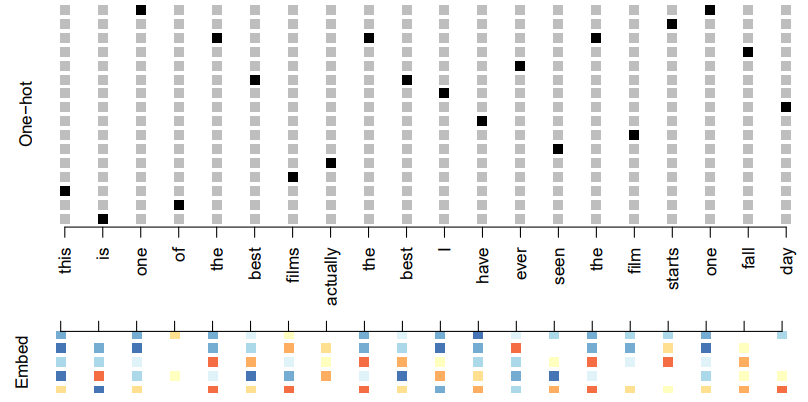

- The document feature is a sequence of words

- We typically truncate/pad the documents to the same number of words (we use )

- Each word is represented as a

one-hot encodedbinary vector of length , with all zeros and a single one in the position for that word in the dictionary - This results in an extremely sparse feature representation, and would not work well

- Instead we use a lower-dimensional pretrained

work embeddingmatrix - This reduces the binary feature vector of length to a real feature vector of dimension (e.g. in the low hundreds)

Word Embedding

- Embeddings are pretrained on very large corpora of documents, using methods similar to principal components

word2vecandGloVeare popular

- After a lot of work, the results are a disappointing accuracy

- We then fit a more exotic

RNNthan the one displayed - aLSTMwithlong and short term memory - Here receives input from (short term memory) as well as from a version that reaches further back in time (long term memory)

- Now we get accuracy, slightly less than the achieved by

glmnet - These data have been used as a benchmark for new

RNNarchitectures - The best reported result found at the time of writing (2020) was aroung

- We point to a leaderboard

Time Series Forecasting

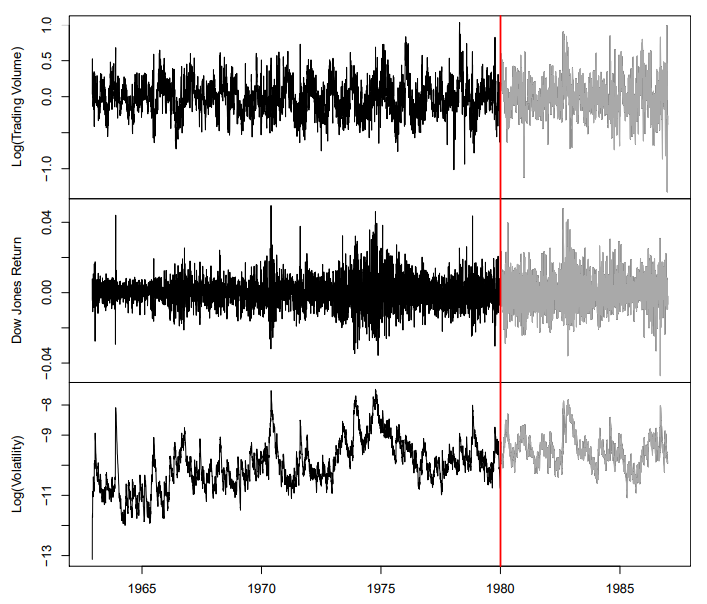

New-York Stock Exchange Data

- Shown in previous slide are three daily time series for the period trading days

Log trading volume: This is the fraction of all outstanding shares that are traded on that day, relative to a -day moving average of past turnover, on the log scaleDow Jones return: This is the difference between the log of theDow JonesIndustrial Index on consecutive trading daysLog volatility: This is based on the absolute values of daily price movements

- Goal : predict

Log trading volumetomorrow, given it observed values up to today, as well as those ofDow Jones returnandLog volatility

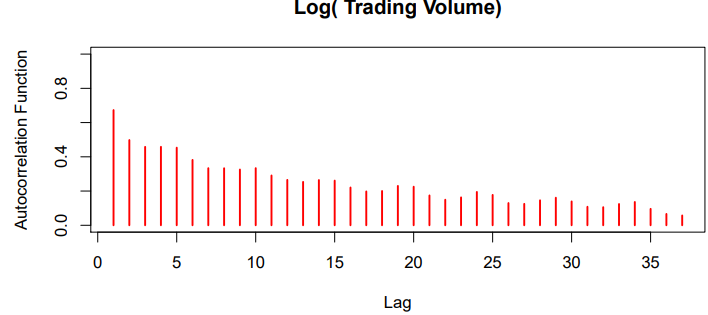

Autocorrelation

- The

autocorrelationat lag is the correlation of all paris that are trading days apart - These sizable correlations give us confidence that past values will be helpful in predicting the future

- This is a curious prediction problem : the response is also a feature

RNN Forecaster

- We only have one series of data

- How do we set up for an

RNN - We extract many short mini-series of input sequences with a predefined length known as the

lag - Since , with we can create such pairs

- We use the first as training data, and the following as test data

- We fit an

RNNwith hidden units per lag step (i.e. per )

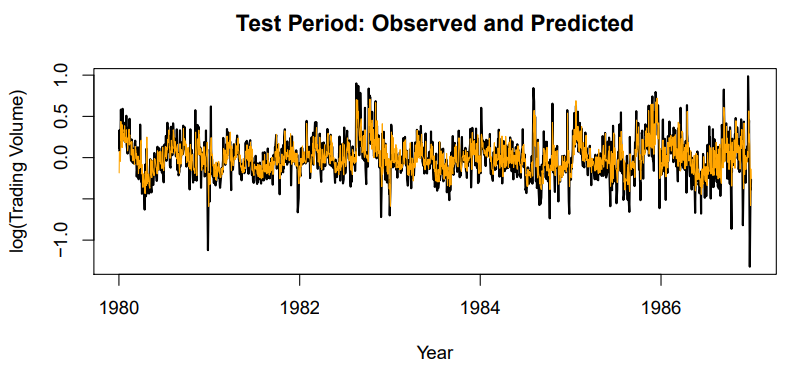

- Figure shows predictions and truth for test period

- for

RNN - for

straw man- use yesterday's value ofLog trading volumeto predict that of today

Autoregression Forecaster

- The

RNNforecaster is similar in structure to a traditionalautoregressionprocedure - Fit an

OSLregression of on , giving - Known as an

order-L autoregressionmodel or - For the

NYSEdata we can include lagged version ofDJ_returnandlog_volatilityin matrix , resulting in columns

- for model ( parameters)

- for

RNNmodel ( parameters) - for model fit by neural network

- for all model if we include

day_of_weekof day being predicted

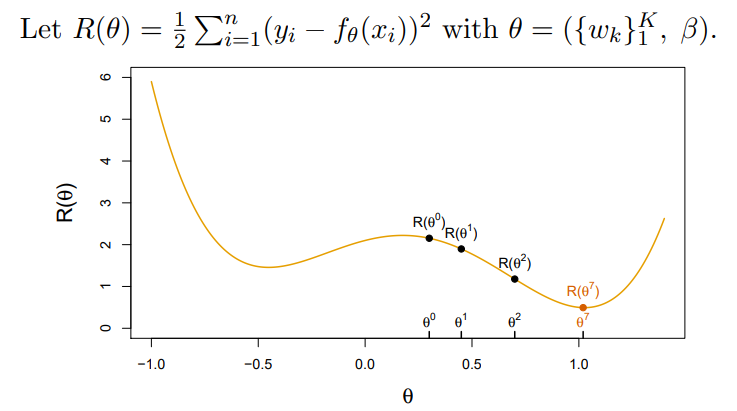

Non Convex Functions and Gradient Descent

- Start with a guess for all the parameters in , and set

- Iterate until the objective fails to decrease :

2.1. Find a vector that reflects a small change in , such thatreducesthe objective

2.2. Set

- In this sample example we reached the

global minimum - If we had started a little to the left of we would have gone in the other direction, and ended up in a

local minimum - Although is multi-dimensional, we have depicted the process as one-dimensional

- It is much harder to identify whether one is in a

local minimumin high dimensions - How to find a direction that point downhill?

- We compute the

gradient vector - i.e. the vector of

partial derivativesat the current guess - The gradient points uphil, so our update is orwhere is the

learning rate(typically small, e.g. )

Gradients and Backpropagation

is a sum, so gradient is sum of gradients

- For ease of notation, let

Backpropagationuses the chain rule for differentitaion

Tricks of the Trade

Slow learning

Gradient descent is slow, and a small learning rate slows it even further. Withearly stopping, this is a form of regularizationStochastic gradient descent

Rather than compute the gradient usingallthe data, use a smallminibatchdrawn at random at each step- An

epochis a count of iterations and amounts to the number of minibatch updates such that samples in total have been processed; i.e. forMNIST Regularization

Ridge and lasso regularization can be used to shrink the weights at each layer. Two other popular forms of regulariztion anddropoutandaugmentation

Droupout Learning

- At each

SGDupdate, randomly remove units with probability , and scale up the weights of those retained by to compensate - In simple scenarios like linear regression, a version of this process can be shown to be equivalent to ridge regularization

- As in ridge, the other units

stand infor those temporaily removed, and their weights are drawn closer together - Similar to randomly omitting variables when growing trees in random forests

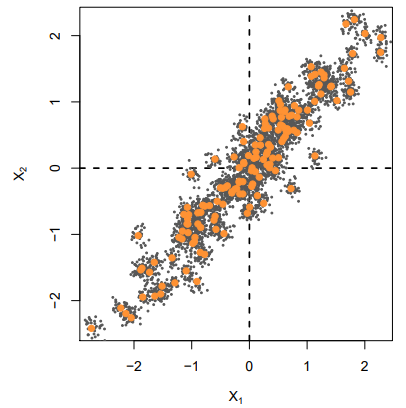

Ridge and Data Augmentation

- Make many copies of each and add a small amount of Gaussian noise to the - a little cloud around each observation - but

leave the copies ofalone - This makes the fit robust to small perturbations in , and is equivalent to

ridgeregularization in anOLSsetting

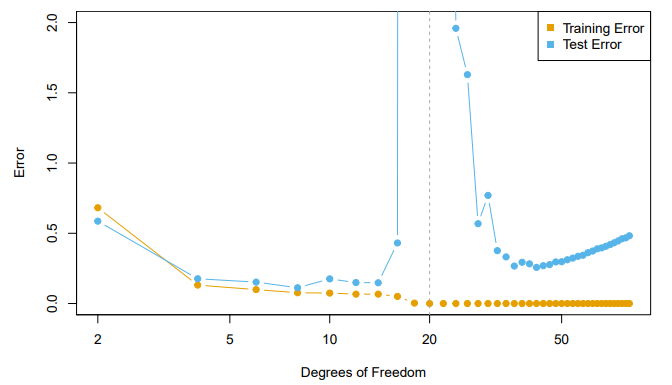

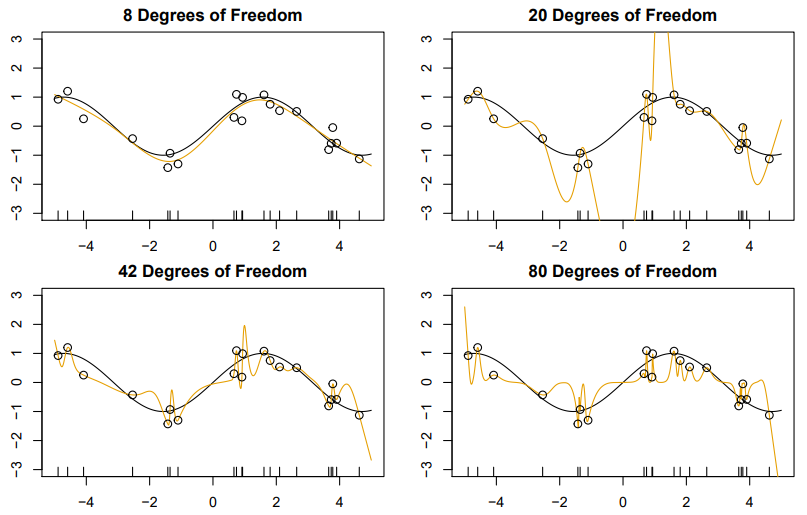

Double Descent

- With neural networks, it seems better to have too many hidden units than too few

- Likewise more hidden layers better than few

- Running stochastic gradients descent till zero training error often gives good out-of-sample error

- Increasing the number of units or layers and again training till zero error sometimes gives

even betterout-of-sample error

- When , model is OLS, and we see usual bias-variance trade-off

- When , we revert to minimum-norm

- As increases above ,

decreasessince it is easier to achieve zero error, and hence less wiggly solutions

- To achieve a zero-residual solution with is a real stretch

- Easier for larger

- In a wide linear model () fit by least squares,

SGDwith a small step size leads to aminimum normzero-residual solution Stochastic gradient flow- i.e. the entire path ofSGDsolutions - is somewhat similar to ridge path- By analogy, deep and wide neural networks fit by

SGDdown to zero training error often give good solutions that generalize well - In particular cases with

high signal-to-noise ratio- e.g. image recognition - are less prone to overfitting; the zero-error solution is mostly signal