Concurrency

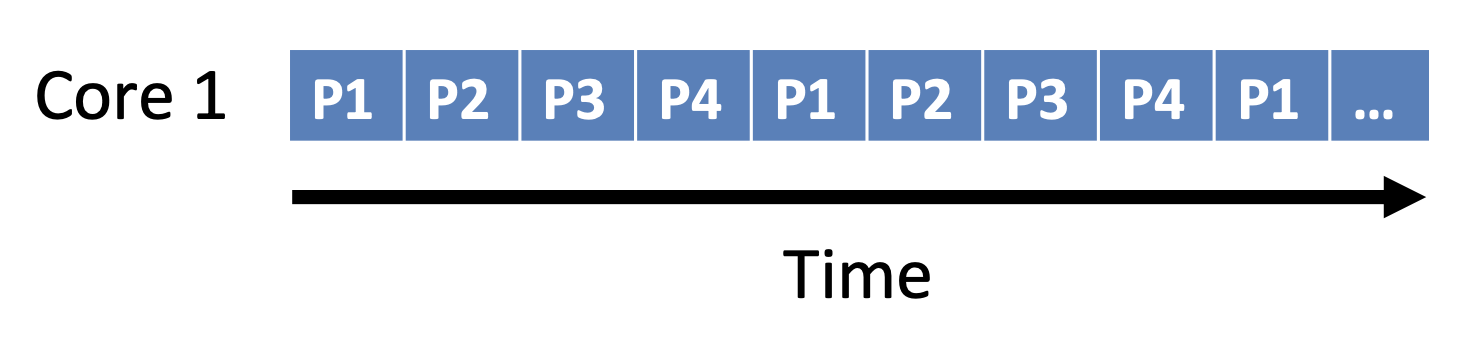

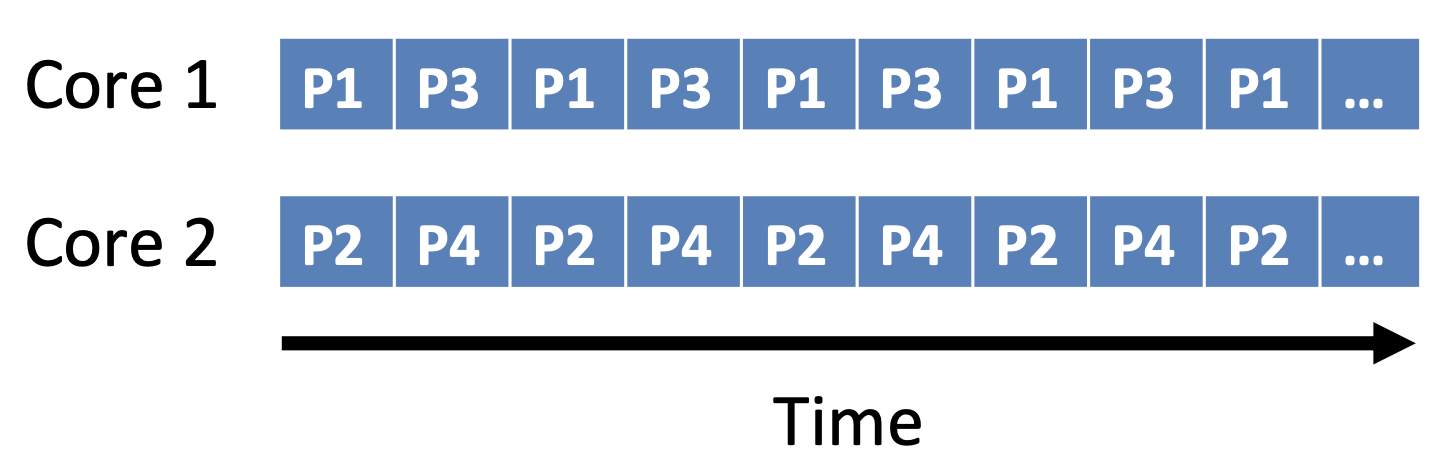

Concurrency vs Parallelism

Concurrency

- Whether processes can access resources (CPU) simultaneously

Parallelism

- Whether actually do multiple tasks at once

Two types of parallelism

- Data parallelism

- Same task executes on many cores

- Task parallelism

- Different tasks execute on each core

- 1 thread handles game AI

- 1 thread handles physics

- Different tasks execute on each core

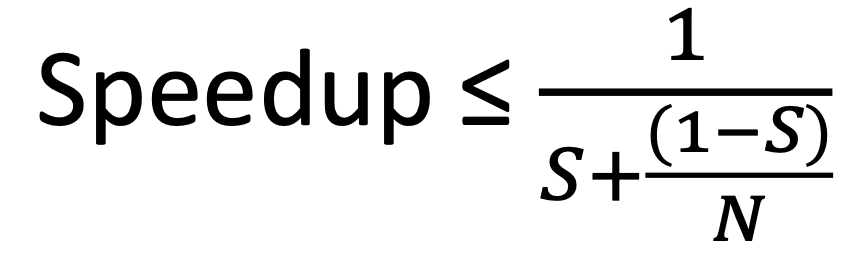

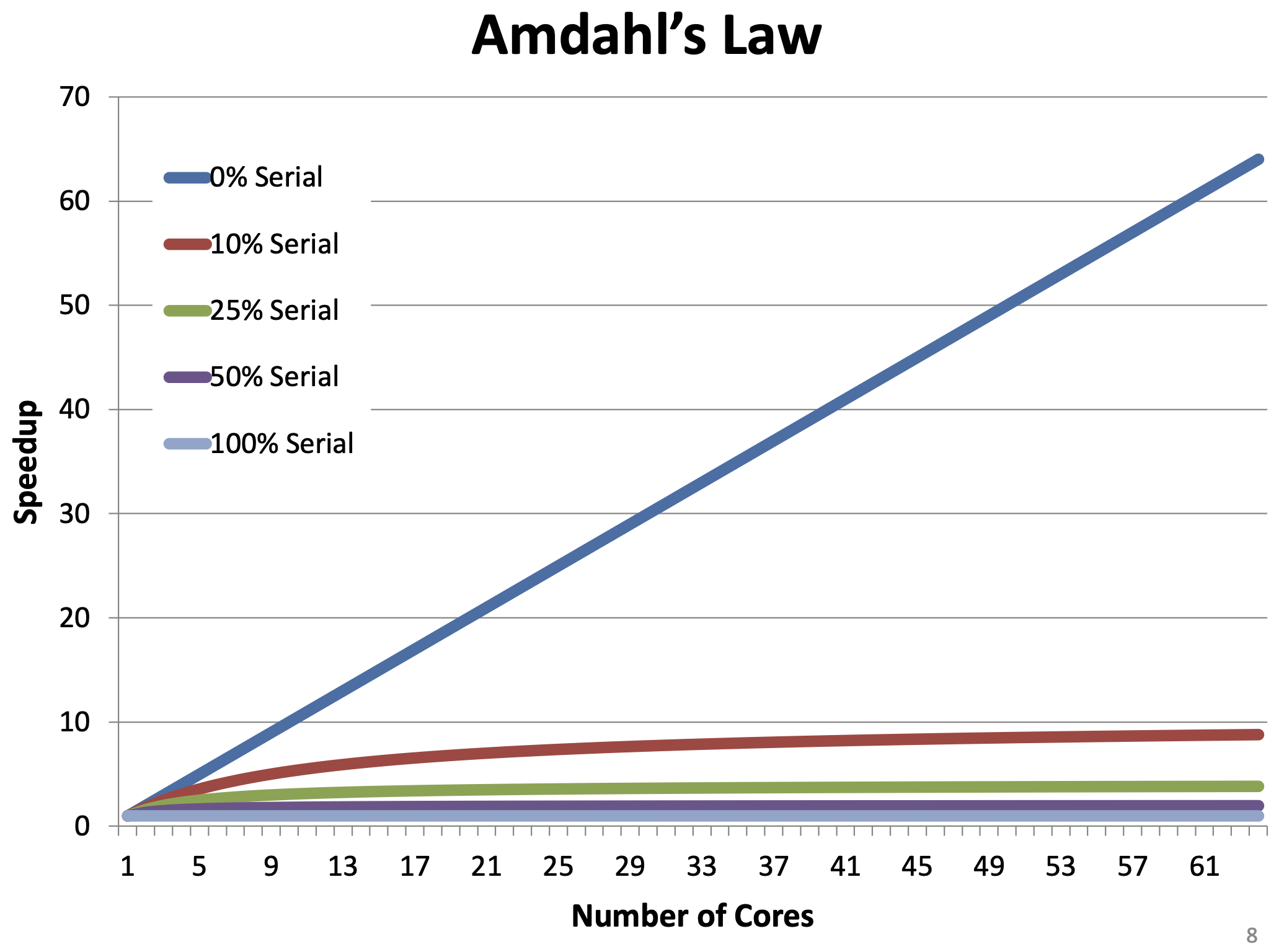

Amdahl's Law

- Upper bound on performance gains from parallelism

- is the fraction of processing time that is serial (non-parallel)

- is the number of CPU cores

- If , speedup approaches

- Speedup is dependent on serial processing time

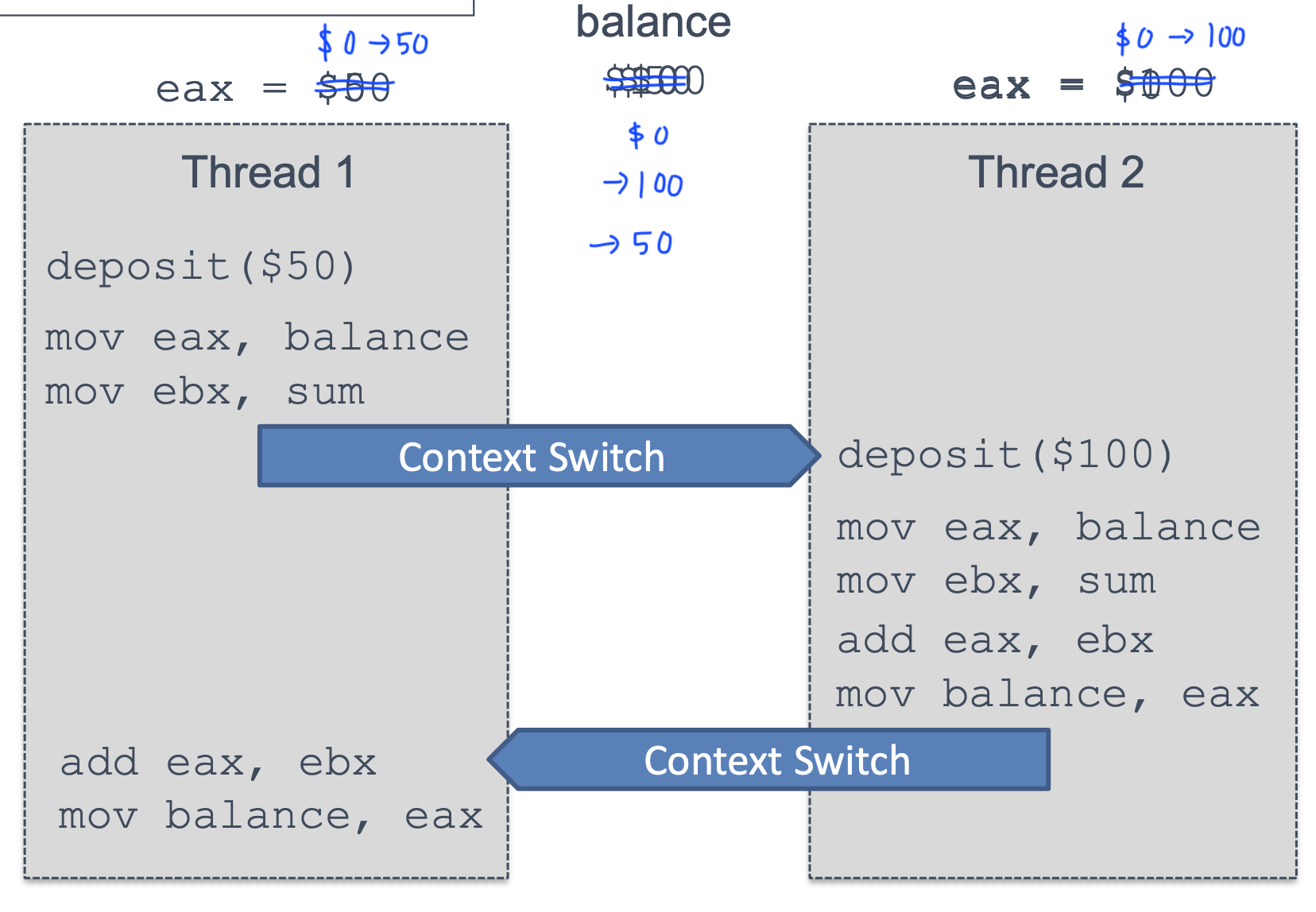

Race Condition

Race Condition

- Multiple threads race to execute code and update shared data

- So, we need to execute sequentially to prevent race condition

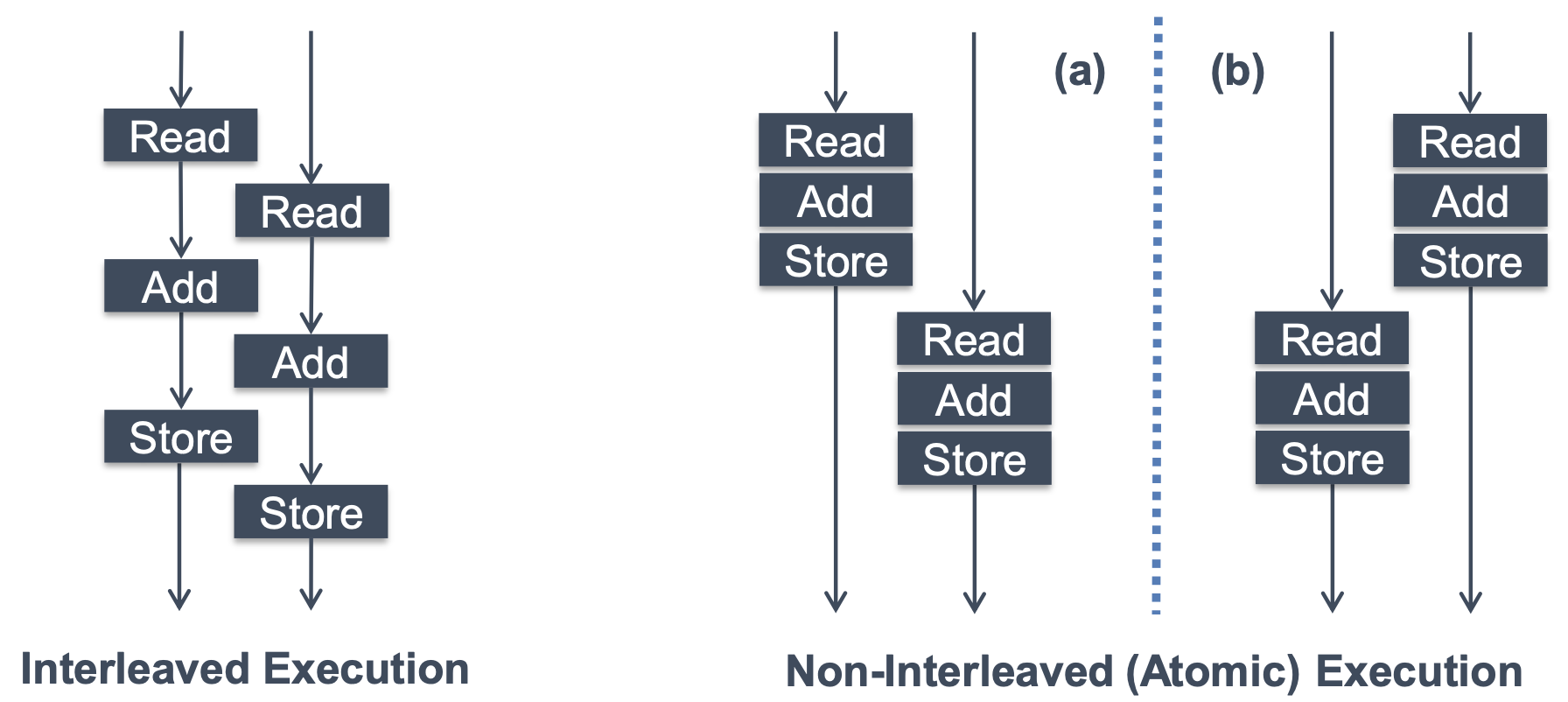

Critical Sections

- Code that accesses a shared resource

that must not be concurrently accessed

by more than one thread of execution - Piece of code is not the problem, but the shared resource is the problem

Atomicity

- If we execute code atomically, these errors can be prevented

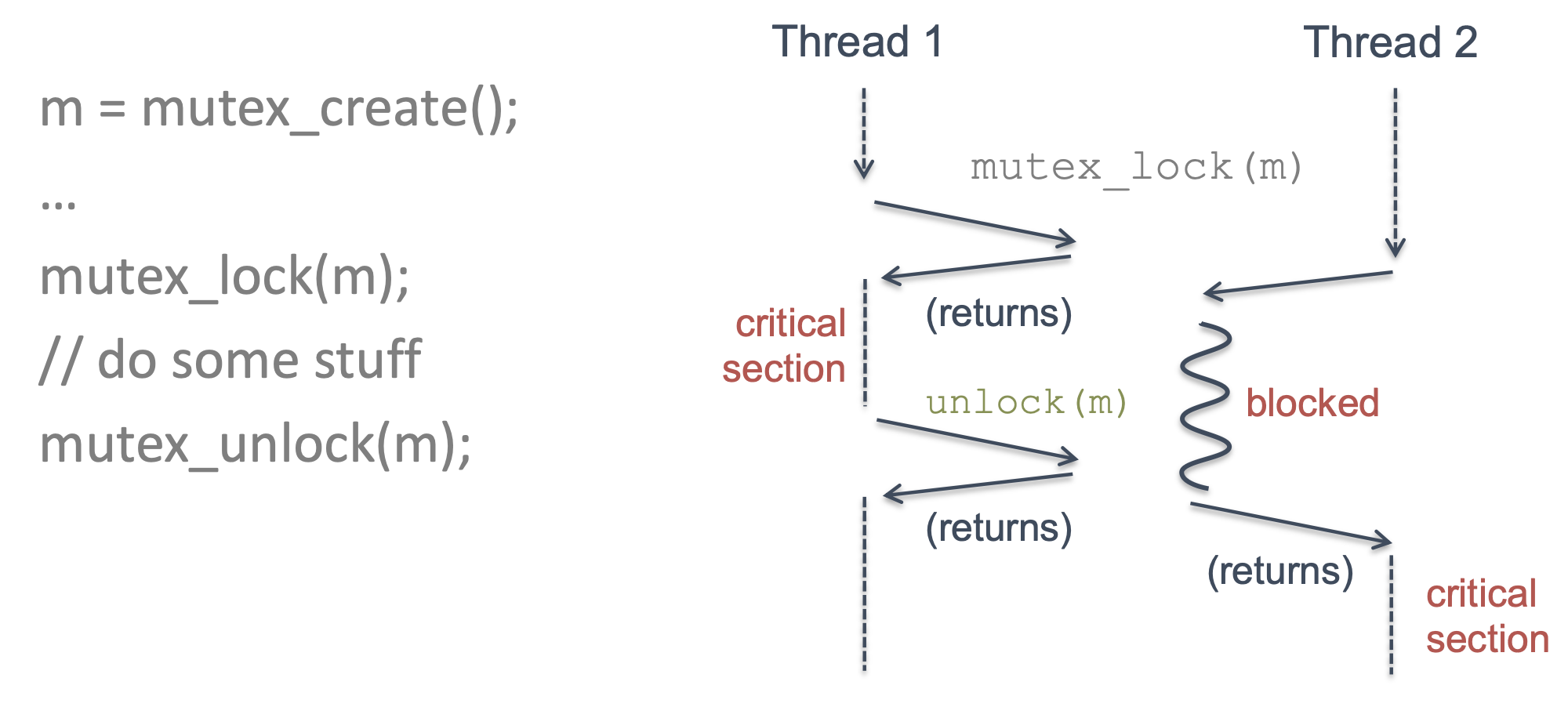

Mutex

- Mutual exclusion lock can enforce atomicity in code

- The section between mutex lock and unlock is critical section

Lock

Lock

- Ensure that critical section executes as if it were a single atmoic instruction

- Access to shared resources must be in the critical section

Semantics

- If no other threads hold the lock, the thread will acquire the lock

- Enter the critical section

- = This thread is the owner of the lock

- Other threads are prevented from entering the critical section

while the first thread that holds the lock is in there

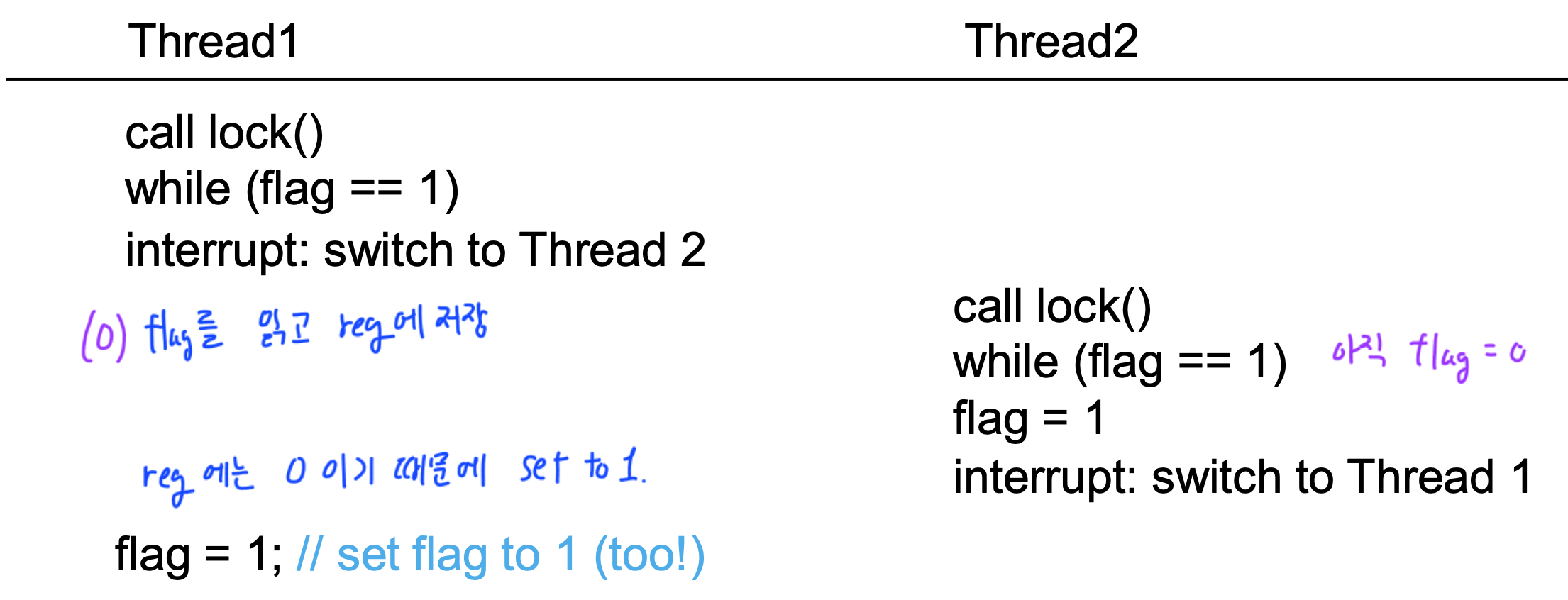

Why needs Hardware support?

- Using a flag denoting whether the lock is held or not

- Flag is shared variable too -> need lock

Problem 1

- No Mutual Exclusion

Problem 2

- Spin-waiting wastes time

So we need an atomic instruction supported by hardware

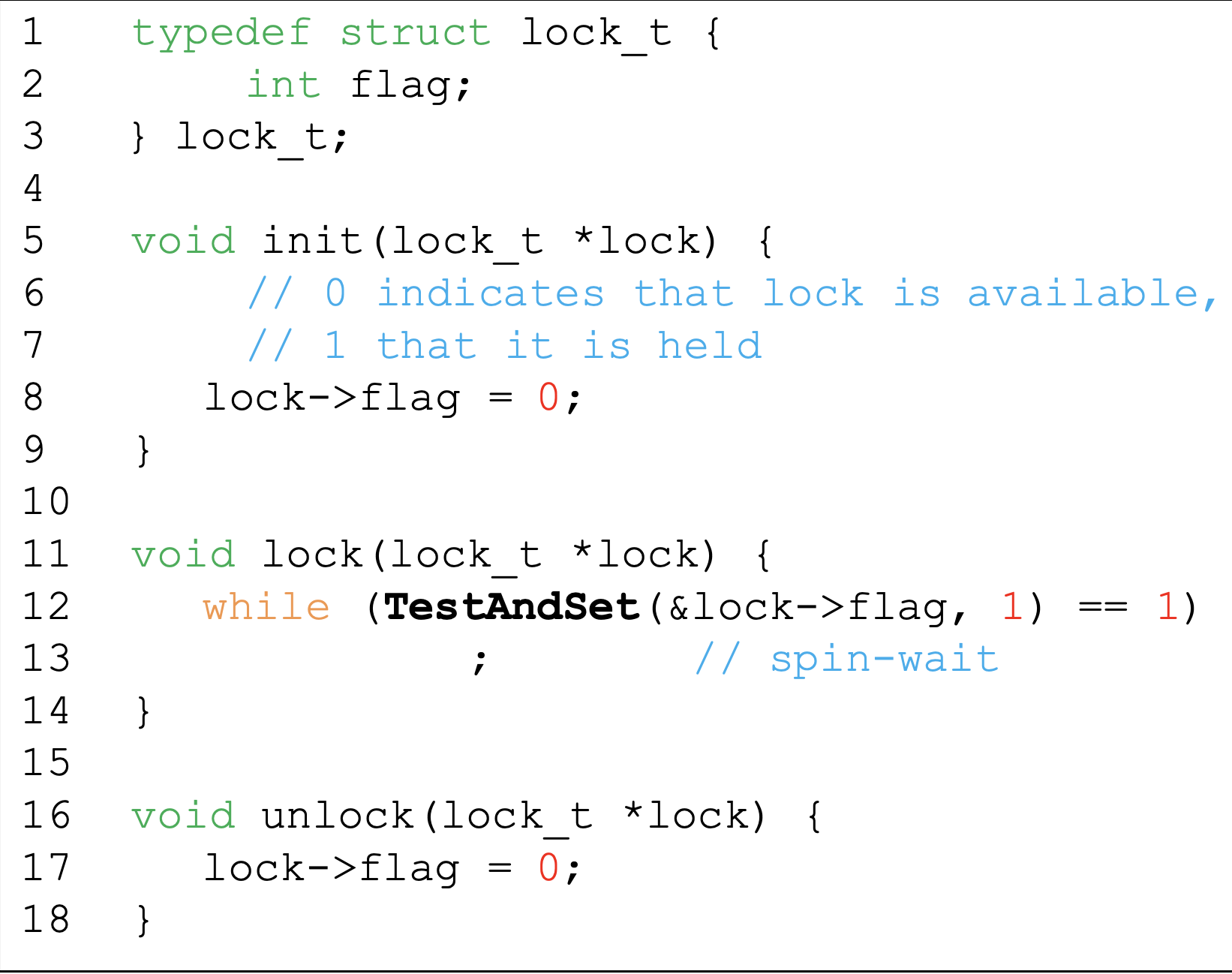

Mutex

Lock and Unlock operations must be atomic

- Test and Set

- Compare and Swap

- Exchange

Well-behaved Mutex

Should guarantees the properties

- Mutual exclusion

- Only one process may hold the lock

- Progress

- The decision about which process gets the lock next cannot be postponed indefinitely

- Bounded waiting

- If all lockers unlock, no process can wait forever

Mutex on a single-CPU system

- The only preemption mechanism is interrupt

- If interrupts are disabled, the currently executing code is atmoic

On Multi CPU

In a multi-CPU system, Data can be read or written by threads, even if interrupts are disable

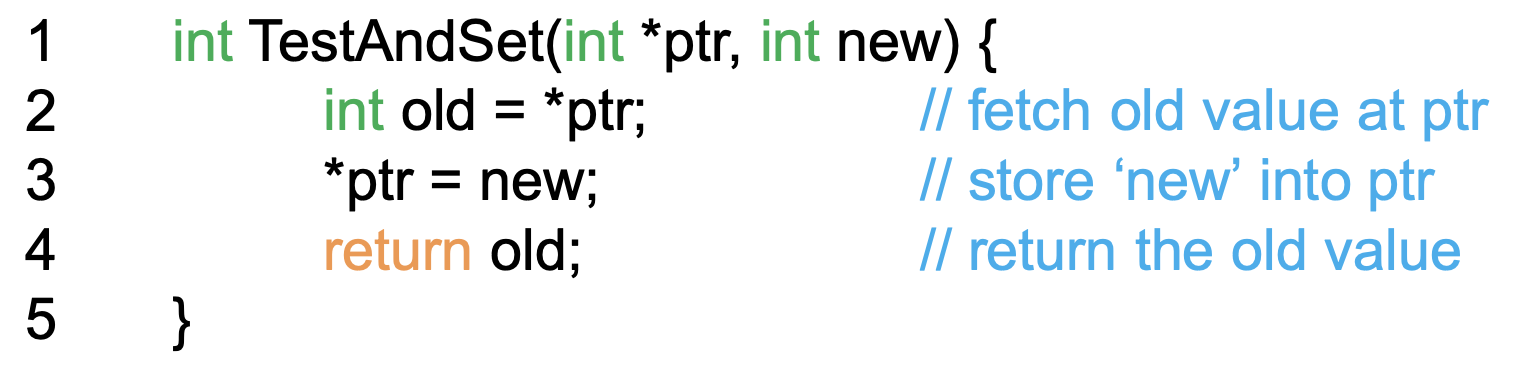

Test and Set

- The operations are performed atomically

Spin Lock using test and set

- First thread will return 0 and break the while loop

- Next threads will return 1 and spin-wait the while loop

Evaluating Spin Locks

- The lock operation is an atomic operation so that guarantees correctness

- Spin locks don't provide any fairness

- A thread spinning may spin forever

- In the single CPU, spinning overhead can be quire painful

- If the instructions in the critical section can be conducted shortly, spin lock can be efficient

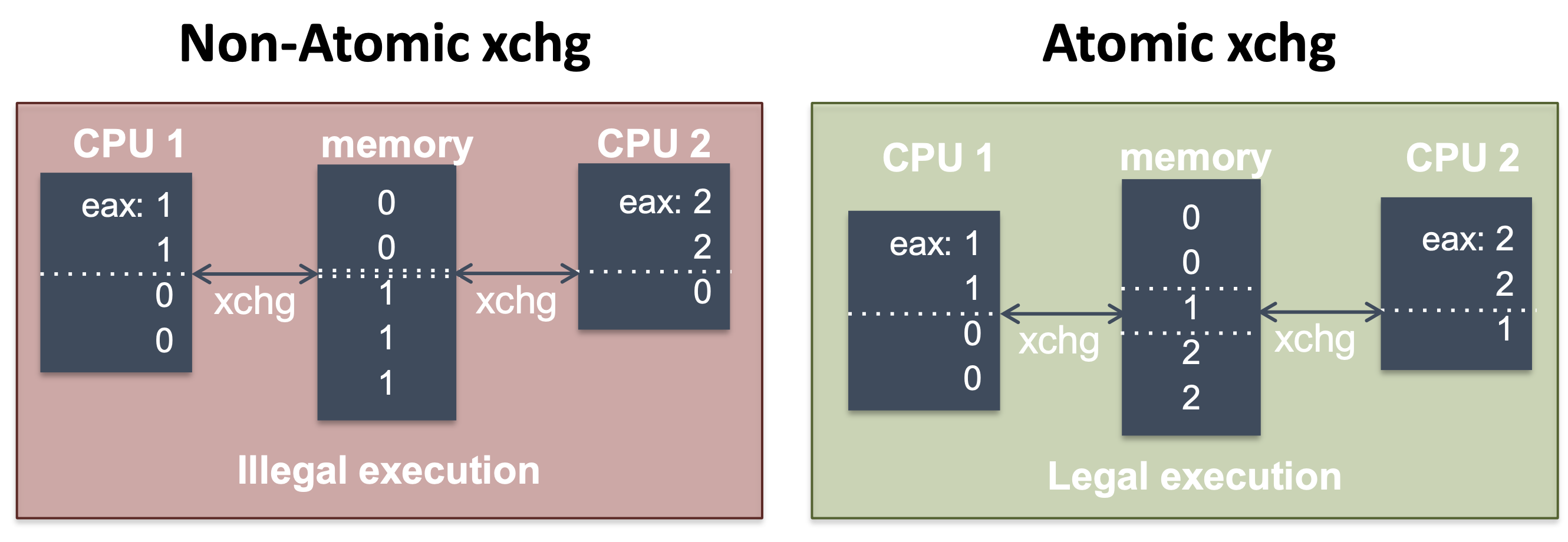

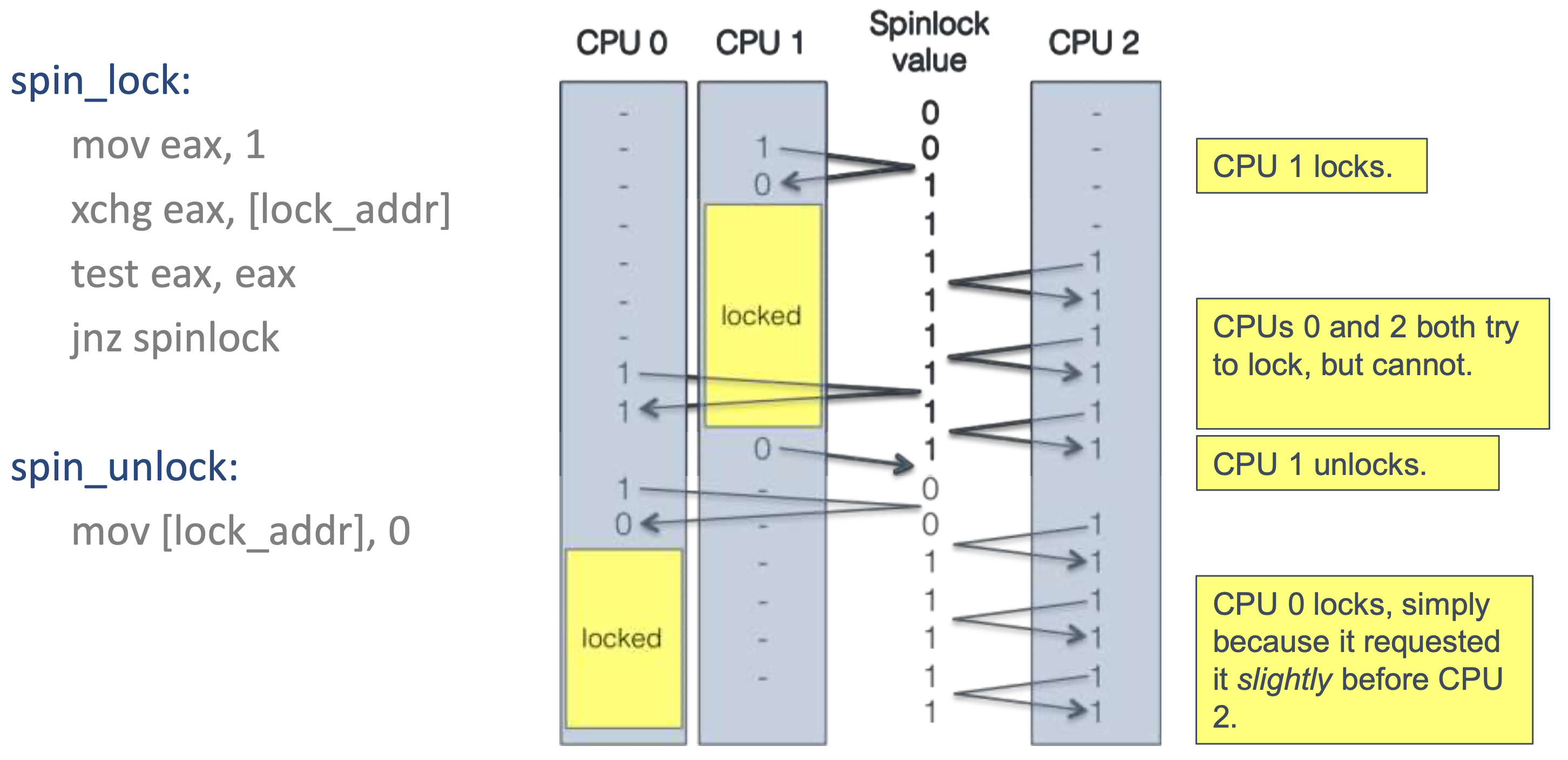

xchg in x86

- lock prefix makes an instruction atomic

lock inc eax;

- xchg is guaranteed to be atomic

xchg eax, [addr];- swap eax and the value in the memory

- Atomicity ensures that each xchg occurs before or after xchg's from other CPUs

- Building a Spin Lock with xchg

test: and operation- If the result is non-zero, loop the spinlock

xchgdo not set the Zero Flag, so we need test

- CPU wastes time because of the spin wait

The price of Atomicity

- Atmoic operations are very expensive on a multi-core system

- Caches must be flushed

- CPU cores may see different values for the same variable

- Case) Some CPUs read a value

-> A CPU acquire the lock and modify the value

-> Other CPUs have different value

-> we need to flush caches

- Memory bus must be locked

- Other CPUs may stall

- May block on the memory bus or atomic instructions

- Caches must be flushed

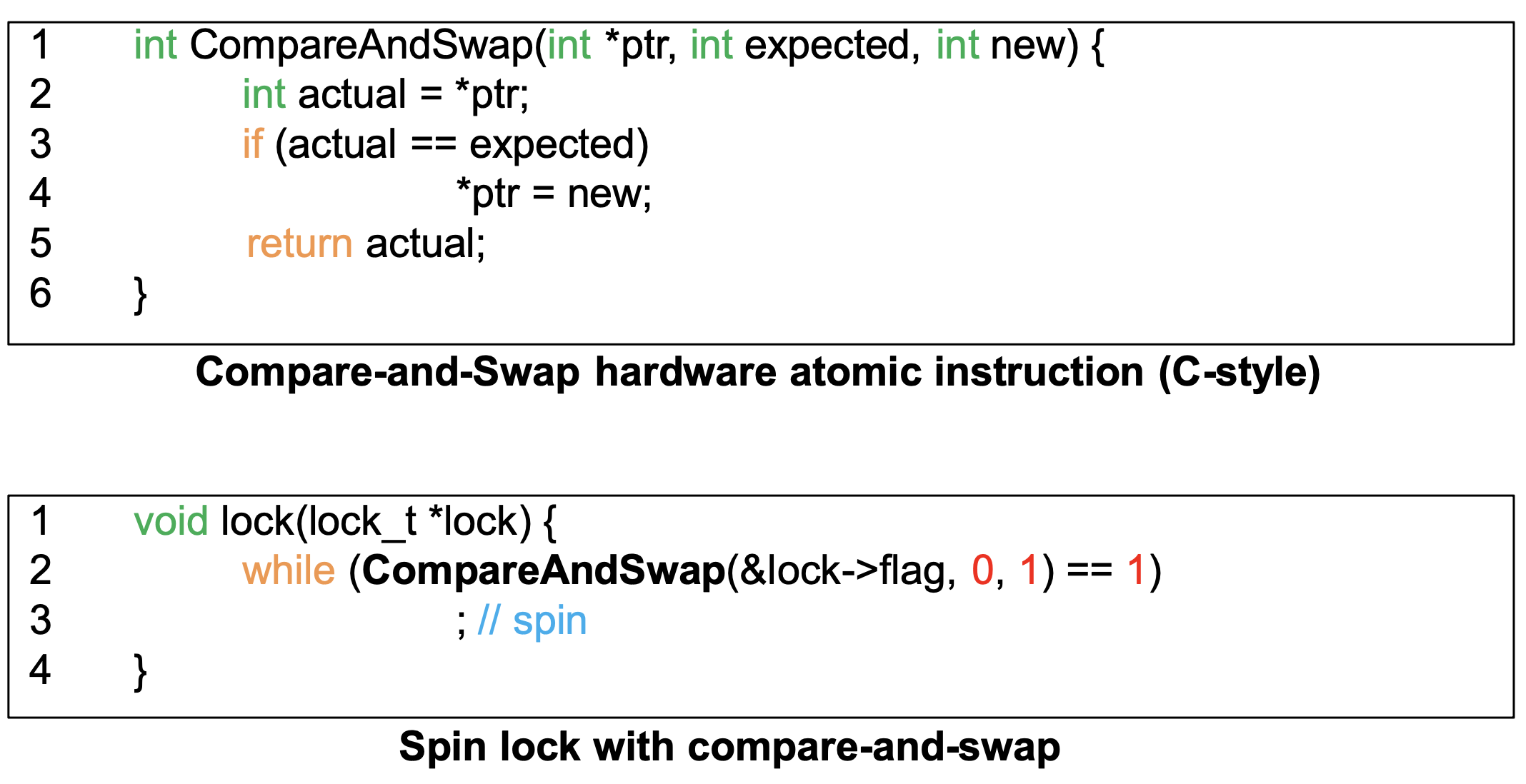

Compare and Swap

- If the value at the address is equal to expected, update the value with the new value

- Return the actual value

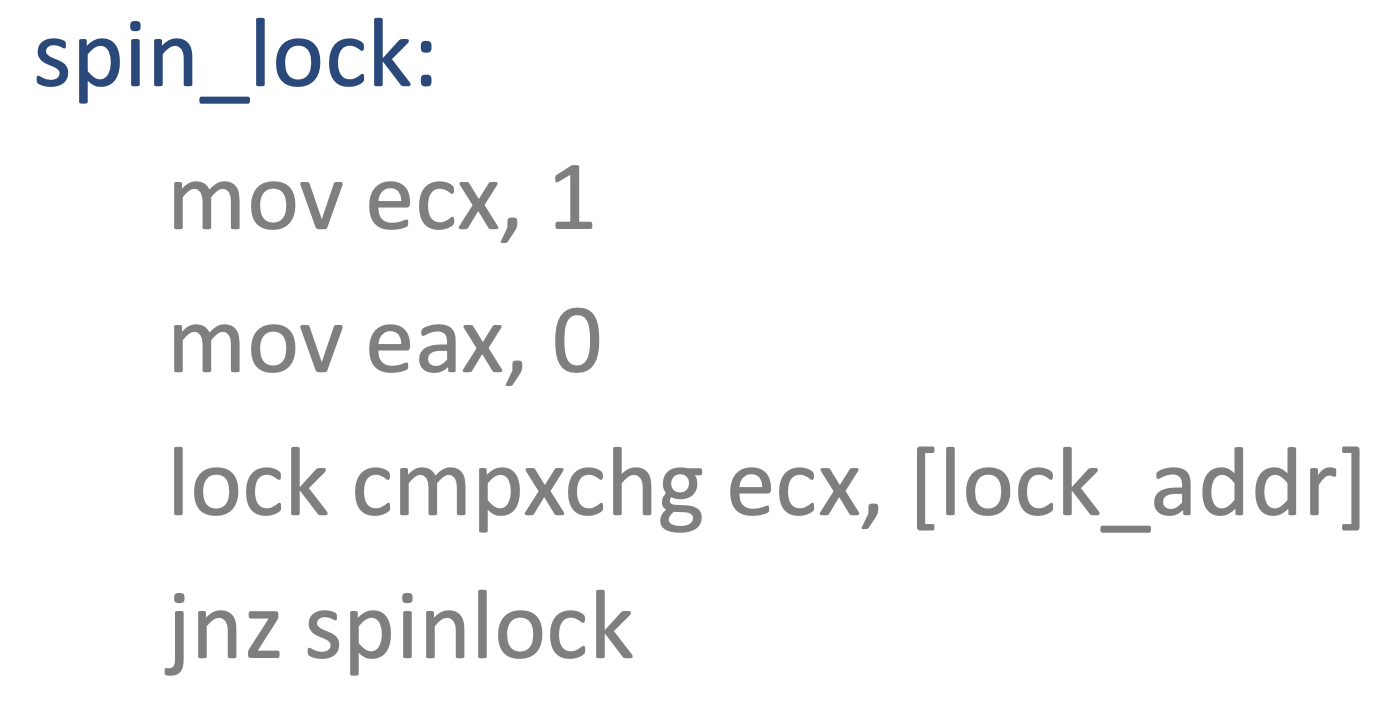

On x86, compare and exchange

- Compare eax(expected) and the value of lock_addr

- If eax == [lock_addr], swap ecx and [lock_addr]

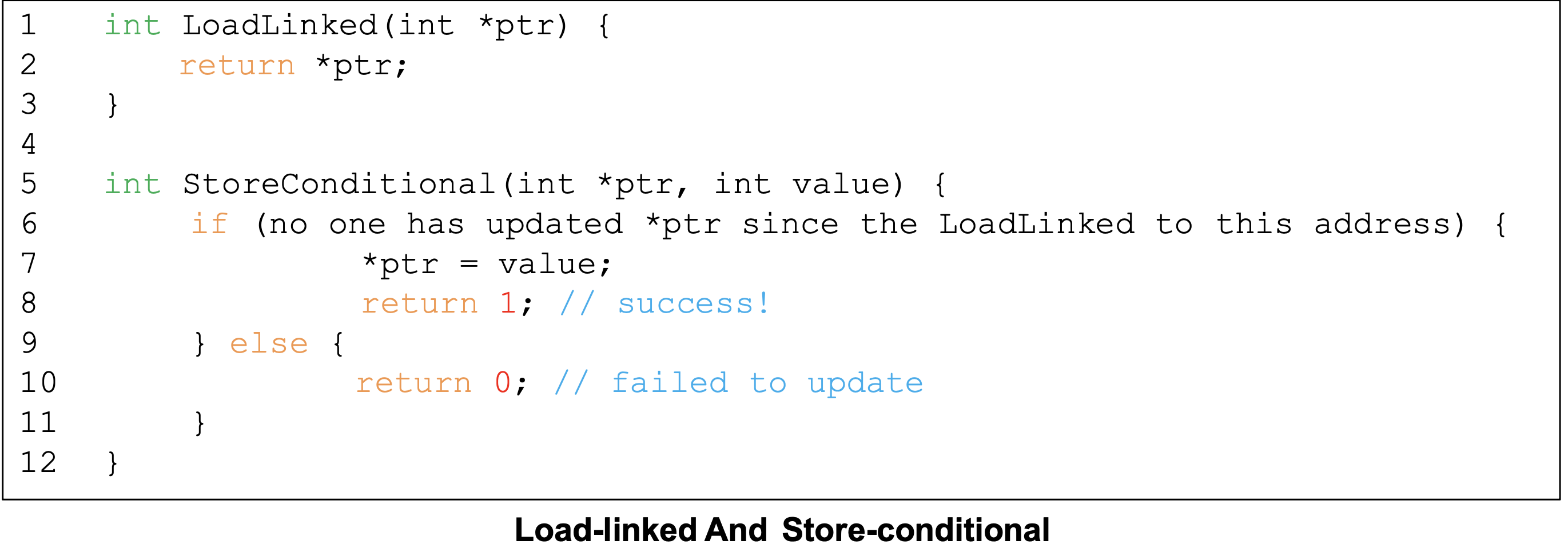

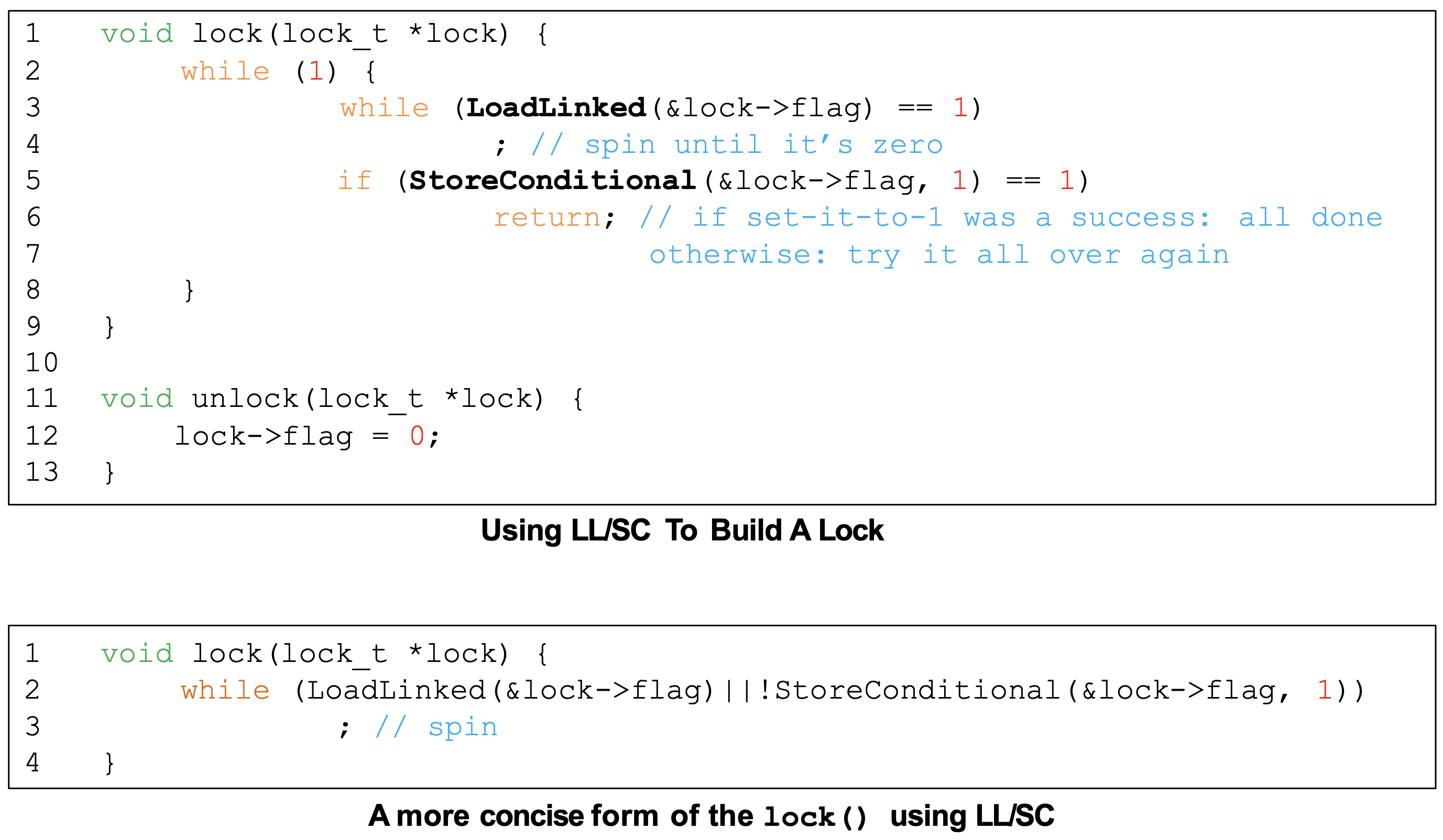

Load-Linked and Store-Conditional

- In RISC architecture, the instruction that operates read and write at once doesn't exist

- If no intermittent store to the address, the store-conditional succeeds

- Since while loop is used twice in code, spinning overhead is too large

-> Concise in 1 line

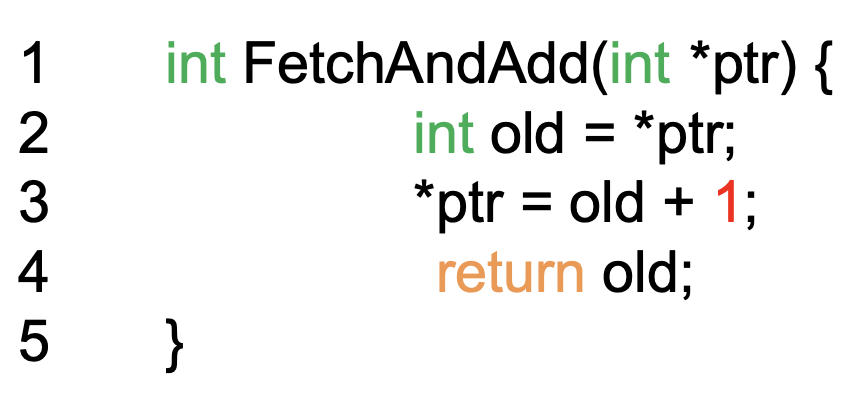

Fetch and Add

- Atomically increment and return old value

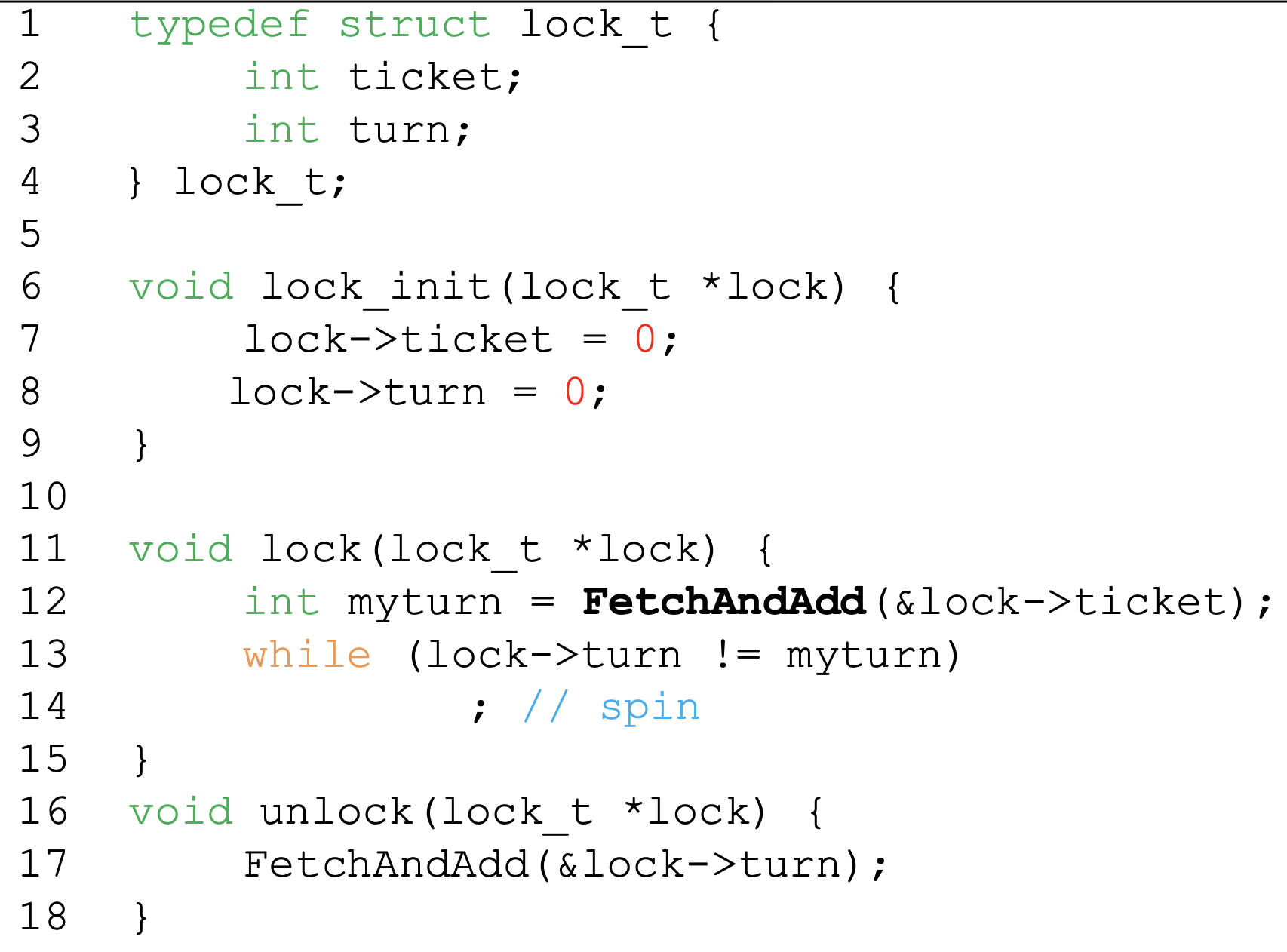

Ticket Lock

- All threads can acquire the lock in order of their requests

-> Ensure fairness

Approaches to handle spinning

- Any time a thread gets caught spinning, it wastes time doing nothing but checking a value

Just yield

- When you are going to spin, give up the CPU

- The cost of a context switch can be substantial and the starvation problem exists

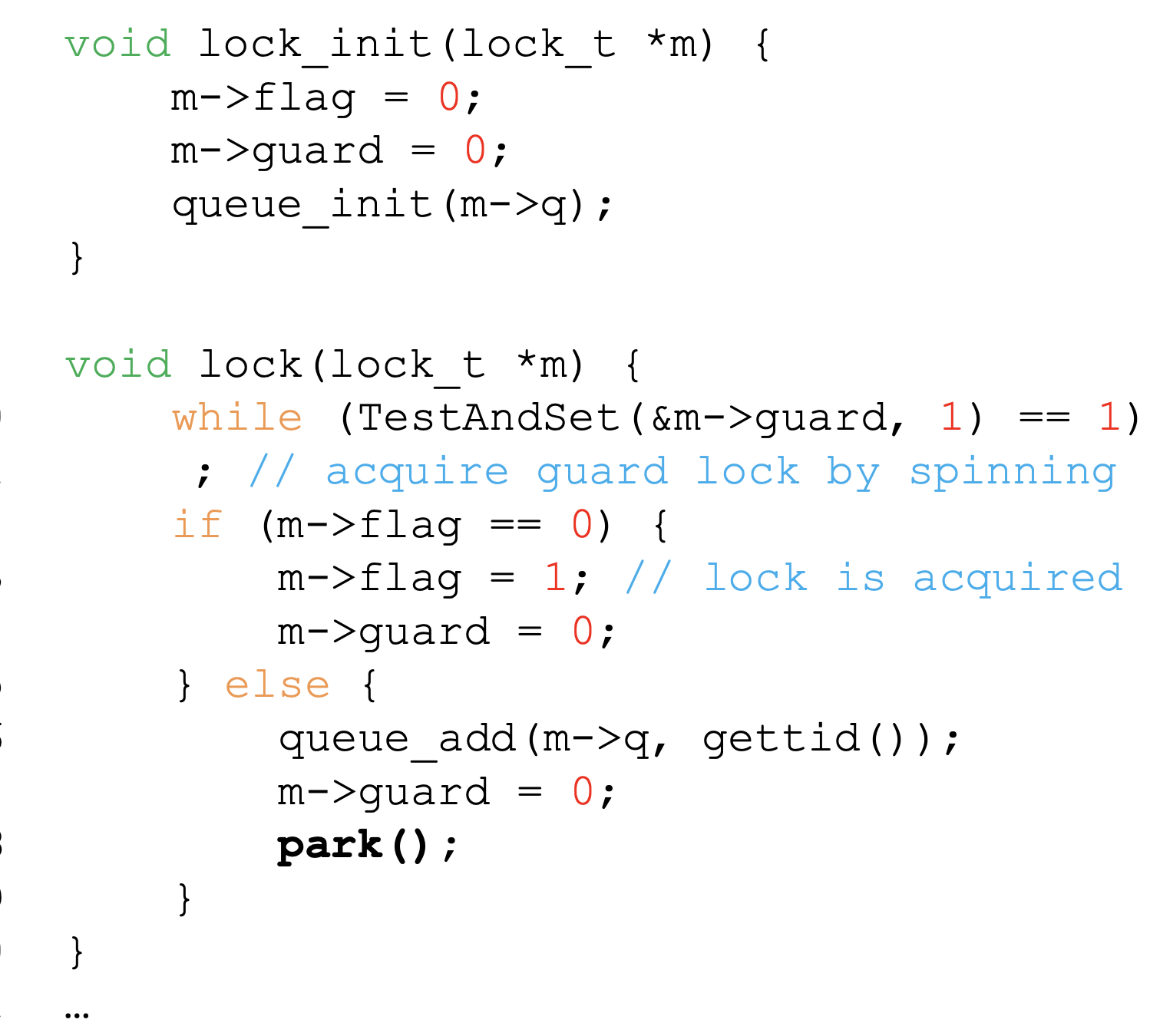

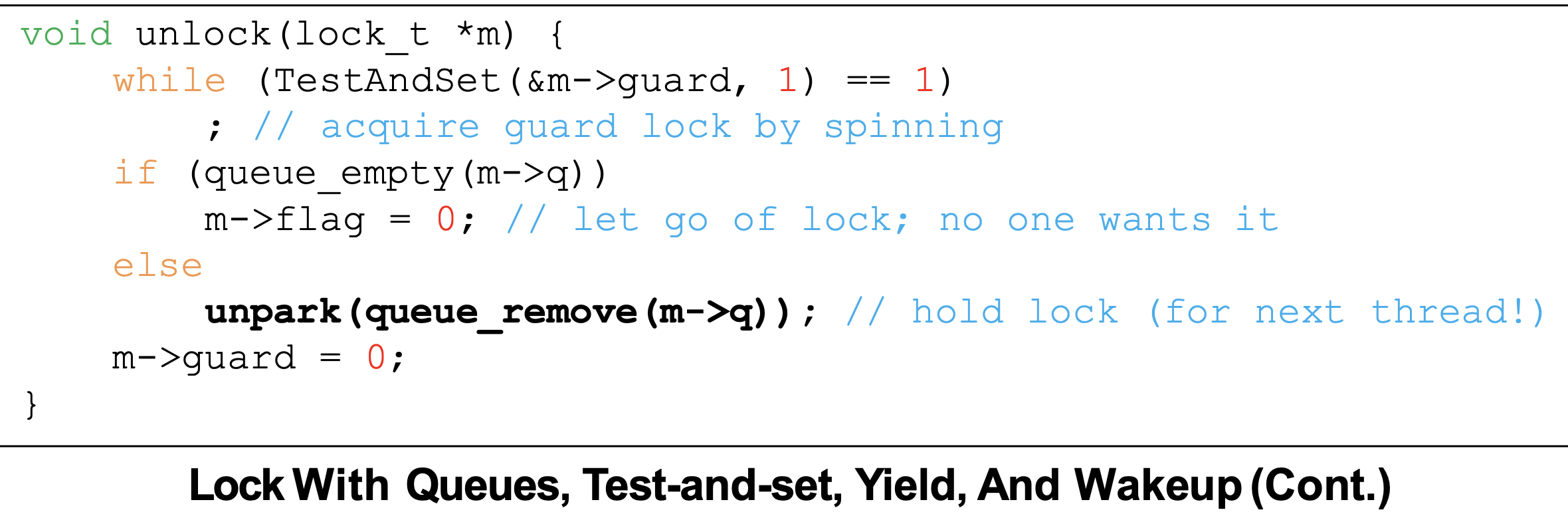

Using Queues

- Sleep until the unlock

- Queue keep tracks of waiting threads

- park()

- Put thread to sleep

- unpark(threadID)

- Wake a particular thread in the queue

- If we send thread straight to the queue without a double lock(flag, guard),

it will take a long time to get the lock - So, sending thread straight to the queue is inefficient if you can get a lock quickly

- Wakeup/waiting race

- Case) Release the lock (thread A) before the call to park() (thread B)

- Thread B sleep forever

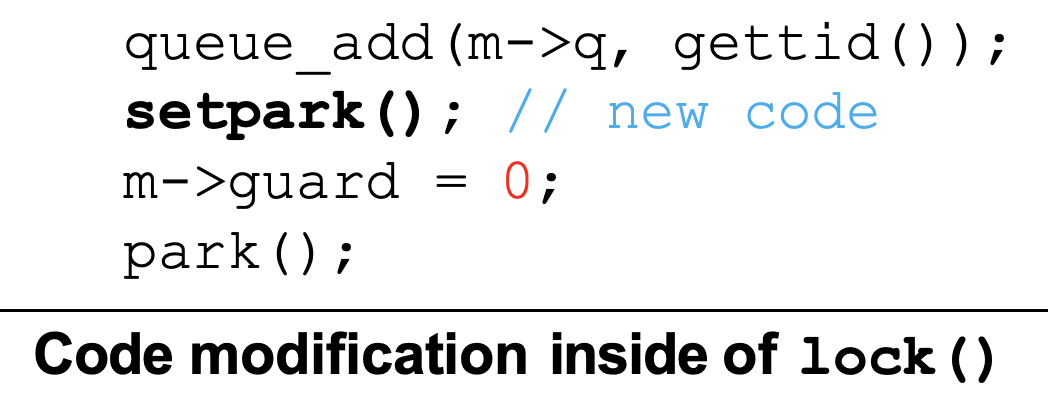

- Solaris add a system call setpark()

- Inform a thread is about to park()

- If another thread calls unpark before park is actually called,

the subsequent park returns immediately instead of sleeping

- Case) Release the lock (thread A) before the call to park() (thread B)

Futex

- Linux provides a futex

- futex_wait(address, expected)

- If the value at address is not equal to expected, returns immediately

- futex_wake(address)

- Wake one thread

- futex_wait(address, expected)

Two-Phase Locks

- Spinning can be useful if the lock is about to be released

First phase

- The lock spins for a while, hoping that it can acquire the lock

- If the lock is not acquired during the first phase, a second phase is entered

Second phase

- The caller is put to sleep