Cross-validation and the Bootstrap

- In the section we discuss two

resamplingmethodsCross-validationBootstrap

- These methods refit a model of interest to samples formed from the

training set, in order to obtain additional information about the fitted model

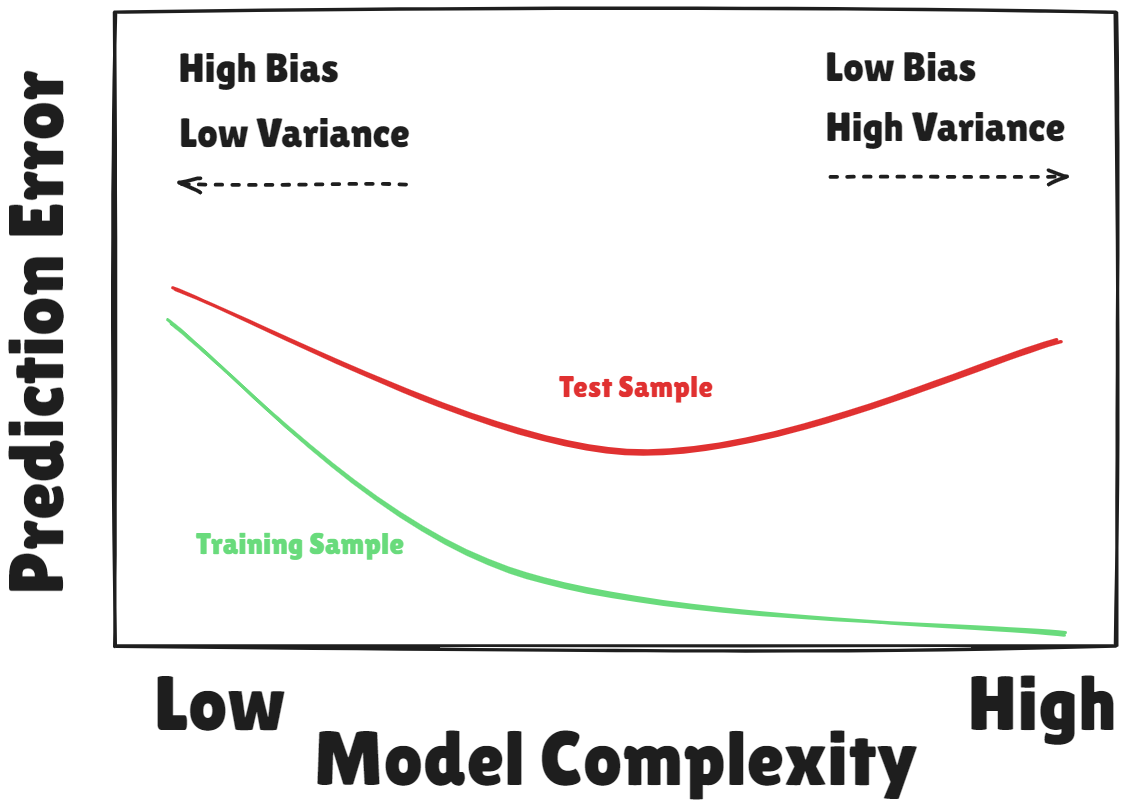

Training Error versus Test Error

- Recall the distinction between the

test errorand thetraining error test erroris the average error that results from using a statistical learning method to predict the response on anew observation, one that was not used in training the methodtraining errorcan be easily calculated by applying the statistical learning method to theobservations used in its trainingBut the

training error rateoften is quite different from thetest error rate, and in particular the former candramatically understimatethe latter

More on prediction-error estimates

- Best solution : a large designated test set. Often not available

- Some methods make a

mathematical adjustmentto thetraining error ratein order to estimate thetest error rate

(These include theCp statistic,AICandBIC) - Here we instead consider a class of methods that estimate the

test errorbyholding outa subset of thetraining observationsfrom the fitting process, and then applying the statistical learning method to those held out observations

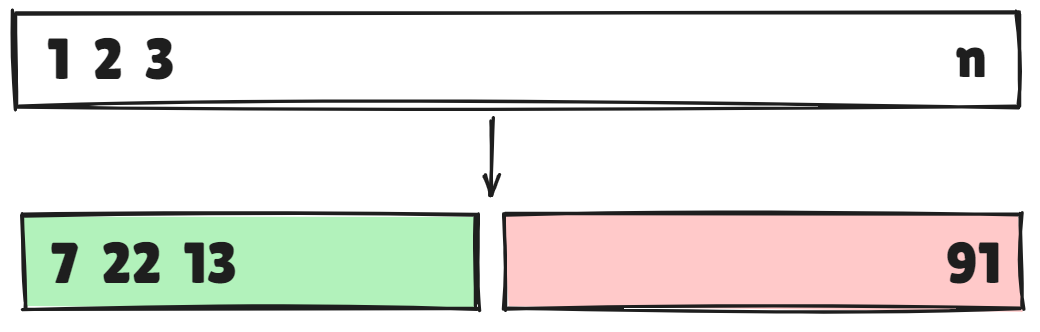

Validation-set approach

- Here we randomly divide the available set of samples into two parts

training setvalidationorhold-out set

- The model is fit on the training set, and the fitted model is used to predict the responses for the observations in the validation set

- The resulting validation-set error provides an estimate of the

test error - This is typically assessed using

MSEin the case of a quantitative response andmisclassification ratein the case of a qualitative (discrete) response

- A random splitting into two halves : left part is training set, right part is validation set

- The

validationestimate of thetest errorcan be highly variable, depending on precisely which observations are included in thetraining setand which observations are included in thevalidation set - This suggests that the

validation set errormay tend tooverestimatethetest errorfor the model fit on the entire data set.

K-fold Cross-validation

Widly used approachfor estimatingtest error- Estimates can be used to select best model, and to give an idea of the

test errorof the final chosen model- Idea is to randomly divide the data into equal-sized parts

- We leave out part , fit the model to the other parts (combined)

- Obtain predictions for the

left-outth part - This is done in turn for each part , and then the results are combined

- Divide data into roughly

equal-sized parts

- Let the parts be , where denotes the indices of the observations in part

- There are observations in part : if is a multiple of , then

- Computewhere , and is the fit for observation , obtained from the data with part removed

- Setting yields -fold or

leave-one out cross-validation(LOOCV) - With least-squares

linearorpolynomial regression, an amazing shorcut makes the cost ofLOOCVthe same as that of a single model fit! The following formula hods:where is the th fitted value from the original least squares fit, and is the leverage(diagonal of the "hat" matrix) LOOCVsometimes useful, but typically doesn'tshake upthe data enough- The estimates from each fold are highly correlated and hence their average can have

high variance - a better choice is or

Other issues with Cross-validation

- Since each training set is only as big as the original training set, the estimates of prediction error will typically be

biased upwardwhy...? - This

biasis minimized when , but this estimate hashigh variance - or provides a good compromise for this

bias-variance tradeoff

Cross-Validation for Classification Problems

- We divide the data into roughly equal-sized parts

- denotes the indices of the observations in part

- There are observations in part : if is a multiple of , then

- Computewhere

- The estimated standard deviation of is

- This is a useful estimate, but strictly speaking,

not quite validwhy...?

Cross-validation: right and wrong

- Consider a simple classifier applied to some two-class data:

- Starting with 5000 predictors and 50 samples, find the 100 predictors having the largest correlation with the class labels

- We then apply a classifier such as logistic regression, using only these 100 predictors

- How do we estimate the test set performance of this classifier?

- Can we apply cross-validation in step 2, forgetting about step 1?

No!

- This would ignore the fact that in Step 1, the procedure

has already seen the labels of the training data, and made use of them - This is a form of training and must be included in the validation process

- It is easy to simulate realistic data with the class labels independent of the outcome, so that true test error , but the CV error estimate that ignores Step 1 is zero!

- We have seen this error made in many high profile genomics papers

The Wrong and Right Way

Wrong: Applycross-validationin step 2Right: Applycross-validationin steps 1 and 2

The Bootstrap

- The

bootstrapis a flexible and powerful statistical tool that can be used to quantify theuncertaintyassociated with a given estimator or statistical learning method - For example, it can provide an estimate of the

standard errorof a coefficient, or aconfidence intervalfor that coefficient

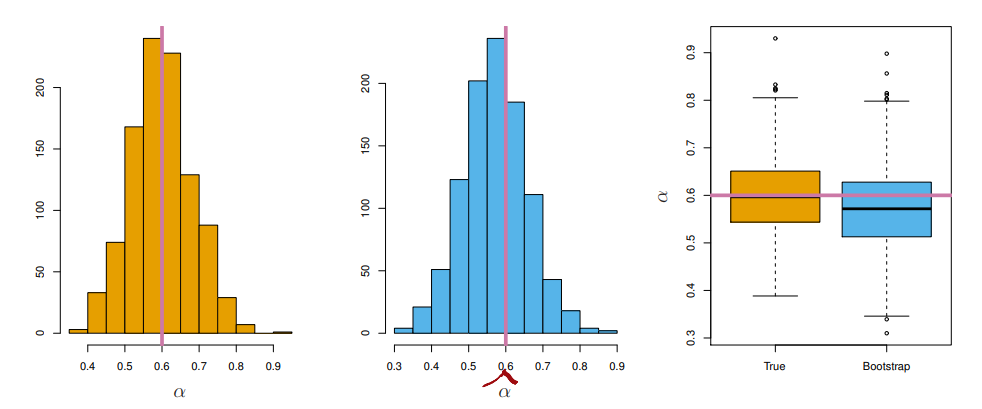

Bootstrap example

- Suppose that we wish to invest a fixed sum of money in two financial assets that yield returns of and , respectively, where and are random quantities

- We will invest a fraction of our money in , and will invest the remaining in

- We wish to choose to

minimizethe totalrisk, orvariance, of our investment - In other words, we want to

minimize - One can show that the value that minimizes the risk given bywhere

- But the values of , and are

unknown - We can compute estimates for these quantities , using a data set that contains measurements for and

- We can then estimate the value of that

minimizesthevarianceof our investment using - To estimate the

standard deviationof , werepeatedthe process of simulating 100 paired observations of and , and estimating 1,000 times - We thereby obtained 1,000 estimates for , which we can call

- So roughly speaking, for a random sample from the population, we would expect to differ from by approximately 0.08, on average

Real world Bootstrap

- The procedure outlined above cannot be applied, because for real data we cannot generate new samples from the original population

- However, the

bootstrapapproach allows us to use a computer to mimic the process of obtaining new data sets, so that we canestimatethevariabillityof our estimate without generating additional samples - Rather than

repeatedlyobtaining independent data sets from the population, we instead obtain distinct data sets by repeatedly sampling observations from the original data set withreplacement

- In more complex data situations, figuring out the appropriate way to generate bootstrap samples can require some thought

- For example, if the data is a time seires, we can't simply sample the observations with replacement

- We can instead create blocks of consecutive observations, and sample those with replacements

- Then we paste together sampled blocks to obtain a bootstrap dataset

Can the bootstrap estimate prediction error?

- In

cross-validation, each of the validation folds is distinct from the other folds used for trainingThere is no overlap

- To estimate prediction error using the

bootstrap, we could think about using each bootstrap dataset as our training sample, and theoriginal sampleas ourvalidation sample - But each bootstrap sample has significant

overlapwith theoriginal data - About two-thirds of the original data points appear in each bootstrap sample

This will cause the

bootstrapto seriously underestimate the true prediction error - The other way around with

original sample=training sample,bootstrap dataset=validation sampleis worseCan partly fix this problem by only using

predictionsfor those observations that did not (by chance) occur in the currentbootstrap sample - But the method gets complicated, and in the end,

cross-validationprovides a simpler, more attractive approach for estimatingprediction error

Pre-validation

Pre-validationcan be used to make a fairer comparison between the two sets ofpredictors- Divide the cases up into

equal-sizedparts of 6 cases each - Set aside one of parts. Using only the data from the other 12 parts, select the features having

absolute correlationat least - 3 with the class labels, and form a

nearest centroidclassification rule - Use the rule to predict the class lables for the 13th part

- Do steps 2 and 3 for each of the 13 parts, yielding a "pre-validated" microarray predictor for each of the 78 cases

- Fit a

logistic regressionmodel to thepre-validatedmicroarray predictor and the 6 clinical predictors

The Bootstrap versus Permutation tests

- The bootstrap samples from the estimated population, and uses the results to estimate

standard errorsandconfidence intervals Permutationmethods sample from an estimatednulldistribution for the data, and use this to estimatep-valuesandFalse Discovery Ratesfor hypothesis tests- The bootstrap can be used to test a

null hypothesisin simple situations - Can also adapt the bootstrap to sample from a

null distributionbut there's no real advantage over permutations

a