Tree-based Methods

- Here we describe

tree-basedmethods for regression and classification - These involve

stratifyingorsegmentingthe predictor space into a number of simple regions - Since the set of splitting rules used to segment the predictor space can be summarized in a tree, these types of approaches are known as

decision-treemethods

Pros and Cons

Tree-basedmethods are simple and useful forinterpretation- However they typically are not competitive with the best supervised learning approaches in terms of prediction accuracy

- Hence we also discuss

bagging,random forests, andboosting - Combining a large number of trees can often result in dramatic improvements in prediction accuracy, at the expense of some loss interpretation

The Basics of Decision Trees

- Decision trees can be applied to both

regreesionandclassificationproblems - We first consider

regressionproblems, and then move on toclassification

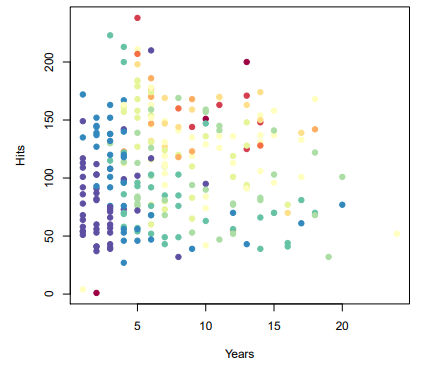

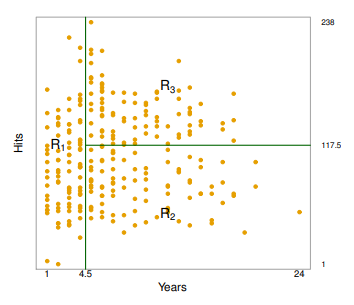

Baseball salary data : how would you stratify it?

- Salary is color-coded from low (blue, green) to high (yello, red)

|  |

|---|

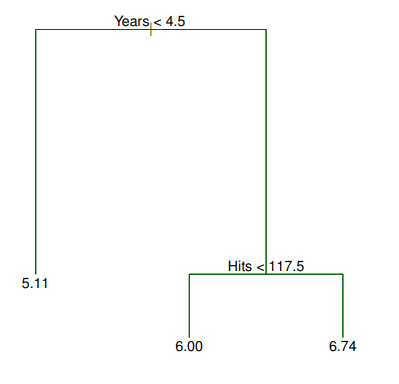

- The tree has two

internalnodes and threeterminalnodes, or leaves - The number in each leaf is the

meanof the response for the observations that fall there - Overall, the tree stratifies or segments the players into three regions of predictor space

Terminology for Trees

- In keeping with the

treeanalogy, the regions , and are known asterminal nodes Decision treesare typically drawnupside down, in the sense that the leaves are at the bottom of the tere- The points along the tree where the predictor space is split are referred to as

internal nodes - In the hitters tree, the two

internal nodesare indicated by the text

and

Interpretation of Results

- is the most important factor in determining and players with less experience earn lower salaries than more experienced players

- Given that a player is less experienced, the number of that he made in the previous year seems to play little role in his

- But among players who have been in the major leagues for five or more years, the number of made in the previous year does affect , and players who made more last year tend to have higher salaries

- Surely an over-simplification, but compared to a

regressionmodel, it is easy to display,interpretand explain

Details of the tree-building process

- We divide the

predictor space- that is, the set of possible values for - into distinct and non-overlapping regions - For every observation that falls into the region , we make the same prediction which is simply the mean of the response values for the training observations in

- In theory, the regions could have any shape,. However, we choose to divide the predictor space into

high-dimensional rectangls, orboxes, for simplicity and for ease ofinterpretationof the resulting predictive model - The goal is to find boxes that

minimizestheRSS, given bywhere is the mean response for the training observations within the th box

- Unfortunately, it is computationally infeasible to consider every possible partition of the feature space info boxes

- For this reason, we take a

top-down,greedyapproach that is known asrecursive binary splitting - The approach is

top-downbecause it begins at the top of the tree and then successively splits thepredictor space - Each split is indicated via two new branches further down on the tree

- It is

greedybecause at each step of the tree-building process, thebestsplit is made at the particular step, rather than looking ahead and picking a split that will lead to a better tree in some future step

Greedy Approach of Tree-building Process

- We first select the predictor and the cutpoint such that splitting the predictor space into the regionsleads to the greatest possible reduction in

RSS - Next, we repeat the process, looking for the

best predictorandbest cutpointin order to split the data further so as tominimizetheRSSwithin each of the resulting regions - However, this time, instead of splitting the entire predictor space, we split one of the two previously identified regions

- Again, we look to split one of these regions further, so as to

minimizetheRSS. The process continues until a stopping criterion is reachedFor instance, we may continue until no region contains more than five observations

Predictions

- We predict the response for a given test observation using the

meanof the training observations in the region to which that test observation belongs - A five-region example of this approach is shown in the next

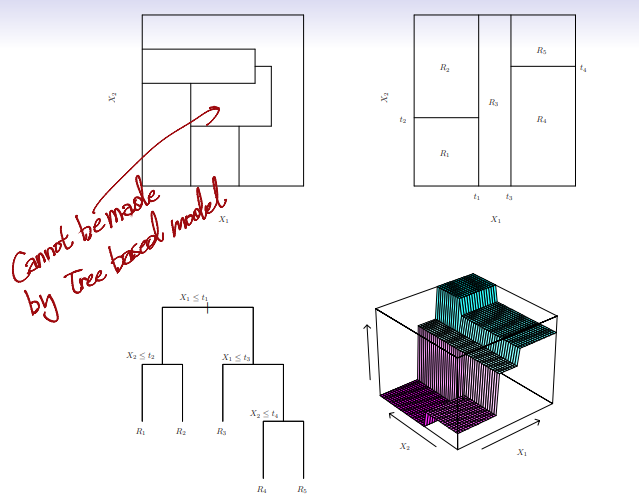

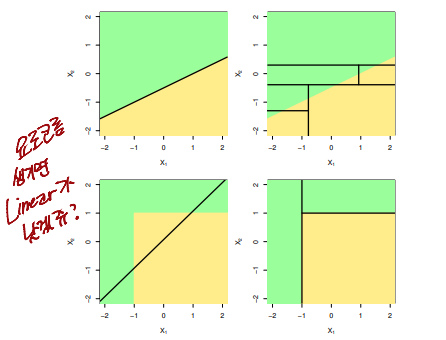

Top Left: A partition of two-dimensional feature space that could not result from recursive binary splittingTop Right: The output of recursive binary splitting on a two-dimensional exampleBottom Left: A tree corresponding to the partition in the top right pannelBottom Right: A perspective plot of the prediction surface corresponding to that tree

Pruning a tree

- The process described above may produce good predictions on the training set, but is likely to

overfitthe data, leading to poor test set perfomance - A

smaller treewith fewer splits (that is, fewer regions ) might lead tolower varianceandbetter interpretationat the cost oflittle bias - One possible alternative to the process described above is to

grow the treeonly so long as thedecrease in the RSSdue to each splitexceedssome (high)threshold - This strategy will result in

smaller trees, but is tooshort-sighteda seemingly worthless split early on in the tree might be followed by a very good split - that is, a split that leads to a large reduction in RSS later on

- A

better strategyis to grow avery large tree, and thenpruneit back in order to obtain asubtree Cost complexity pruning- also known asweakest link pruning- is used to do this- We consider a sequence of trees indexed by a

nonnegativetuning parameter - For each value of there corresponds a

subtreesuch thatRSS:- Number of

Terminal Node:

- Here indicates the number of

terminal nodesof the Tree is the rectangle(i.e. the subset of predictor space) corresponding to the thterminal node, and is the mean of the trainin observations in

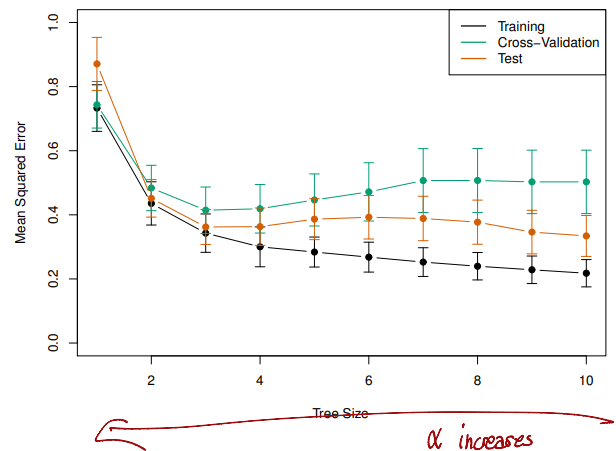

Choosing the best subtree

- The tuning parameter controls a

trade-offbetween the subtree'scomplexityand itsfitto the training data - We select an

optimal valueusingcross-validation - We then return to the full data set and obtain the subtree corresponding to

Summary : tree algorithm

- Use

recursive binary splittingto grow a large tree on the training data,stoppingonly when eachterminal nodehasfewerthan someminimumnumber of observations - Apply cost

complexitypruning to the large tree in order to obtain a sequence ofbest subtrees, as a function of - Use -fold

cross-validationto choose . For each- Repeat Steps 1 and 2 on the th fraction of the training data, excluding the th fold

- Evaluate the

mean squared prediction erroron the data in the left-out th fold, as a function of

- Return the

subtreefromStep 2that corresponds to the chosen value of

Then we could pick value when the

Tree Sizehas become 3 using 1 std rule

Classification Trees

- Very similar to a

regression tree, except that it is used to predict aqualitative responserather than aquantitativeone - For a

classification tree, we predict that each observation belongs to themost commonly occurring classof training observations in the region to which it belongs - Just as in the

regressionsetting, we userecursive binary splittingto grow aclassification tree - In the

classificationsetting,RSScannot be used as a criterion for for making thebinary splits

- A natural alternative to

RSSis theclassification error rateHere represents the proportion of training observations in the th region that are from the th class. - However

classification erroris not sufficiently sensitive fortree-growing, and in practice two other measures are preferable

Gini index and Deviance

- The

Gini indexis defined by - For this reason the

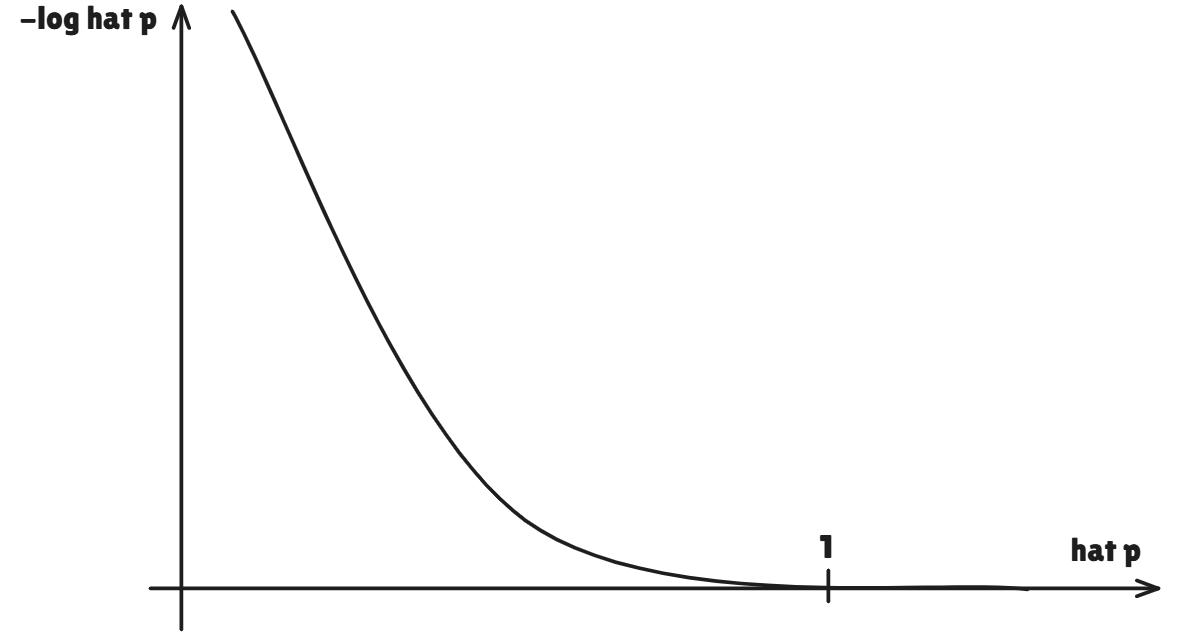

Gini indexis referred to as a measure of nodepurity- a small value indicates that anodecontains predominantly observations from a single class - An alternative to the

Gini indexiscross-entropy, given by

- It turns out that the

Gini indexand thecross-entropyare very similar numerically

Trees Versus Linear Models

- Top Row : True

linearboundary - Bottom Row : true

non-linear boundary - Left Column :

Linear model - Right Column :

non-linear model

Advantages and Disadvantages of Trees

- Advantages

- Trees are very easy to explain to people. They are even easier to explain than

linear regression - Some people believe that

decision treesmore closely mirror humandecision-makingthan do theregressionandclassificationapproaches seen in previous chapters - Trees can be displayed

graphicallyand are easilyinterpretedeven by a non-expert - Trees can easily handle

qualitativepredictors without the need to create dummy variables

- Trees are very easy to explain to people. They are even easier to explain than

- Disadvantages

- Unfortunately, trees generally do not have the same level of

predictive accuracyas some of the otherregressionandclassificationapproaches seen in this book

- Unfortunately, trees generally do not have the same level of

Bagging

Bootstrap aggregation, orbagging, is a general-purpose procedure forreducing the varianceof a statistical learning method- Recall that given a set of independent observations , each with variance the

varianceof themeanof the observations is given by - In other words,

averaginga set of observationsreduces variance - Of course, this is not practical because we generally do not have access to multiple training sets

- Instead, we can

bootstrap, by taking repeated samples from the (single) training data set - In this approach we generate different

bootstrappedtraining data sets - We train our method on the th

bootstrappedtraining set in order to get , the prediction at a point - We then average all the predictions to obtain

This is called

bagging

Bagging classification trees

- The above prescription applied to

regression trees - For

classification trees: for each test observation, we record the class predicted by each of the trees, and take amajority vote

- The

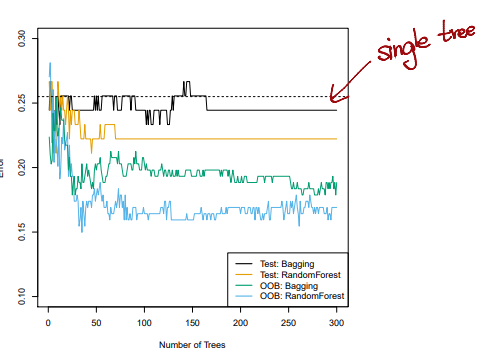

test error(black and orange) is shown as a function of , the number ofbootstrappedtraining sets used Random forestswere applied with- The dashed line indicates the test error resulting from a

singleclassificaion tree - The green and blue traces show the

OOBerror, which in this case is considerably lower

- The

Out-of-Bag Error Estimation

- It turns out that there is a very straightforward way to estimate the test error of a

bagged model - Recall that the key to

baggingis thattreesare repeatedly fit tobootstrappedsubsets of the observations - One can show that on

average, eachbaggedtree makes use of aroundtwo-thirdsof the observations - The remaining

one-thirdof the observations not used tofita givenbagged treeand referred to as theout-of-bag(OOB) observations - We can predict the response for the th observation using each of the trees in which that observation was

OOB - This will yield aroung predictions for the th observation, which we

average - This estimate is essentially the

LOOcross-validation errorforbagging, if islarge

Random Forests

Random forestsprovide an improvement overbagged treesby way of a small tweak thatdecorrelatesthe trees- This reduces the

variancewhen weaveragethe trees - As in

bagging, we build a number ofdecision treesonbootstrappedtraining samples - But when building these

decision trees, each time a split in a tree is considered, arandom selectionof predictors is chosen as split candidates from the full set of predictors - The split is allowed to use only one of those predictors

- A fresh selection of predictors is taken at each split, and typically we choose

That is, the number ofpredictorsconsidered at each split is approximately equal to the square root of the total number of prdictors

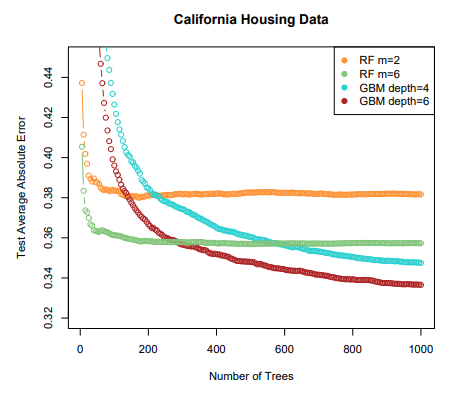

Boosting

- Like

bagging,boostingis a general approach that can be applied to many statistical learning methods forregressionorclassification - We only discuss

boostingfor decision trees - Recall that

bagginginvolves creating multiple copies of the original training data set using thebootstrap,fittinga seperate decision tree to each copy, and then combining all of the trees in order to create asingle predictive model - Notably, each tree is built on a

bootstrapdata set, independent of the other trees Boostingworks in a similar way, except that the trees are grownsequentially

Boosting algorithm for regression trees

- Set and for all in the training set

- For , repeat :

- Fit a tree with splits

terminal nodesto the training data - Update by adding in a

shrunkenversion of the new tree : - Update the residuals

- Fit a tree with splits

- Output the

boosted model

What is the idea behind this procedure?

- Unlike fitting a single large decision tree to the data, which amounts to

fitting the data hardand potentially overfitting, theboostingapproach insteadlearns slowly - Given the current model, we fit a decision tree to the residual from the model

- We then add this new

decision treeinto thefitted functionin order to update the residuals - Each of these trees can be rather

small, with just a fewterminal nodes, determined by the parameter in the algorithm - By

fittingsmall trees to theresiduals, we slowly improve in areas where it does not perform well - The

shrinkage parameterslows the process down even further, allowing more and different shaped trees to attack the residuals

Boosting for classification

Boostingforclassificationis similar in spirit toboostingforregression, but is a bit morecomplex- We will not go into detail here, nor do we in the text book

- Students can learn about the details in Elements of Statistical Learning, chapter 10

Tuning parameters for boosting

- The

number of trees

Unlikebaggingandrandom forests,boostingcanoverfitif is too large, although this overfitting tends to occur slowly if at all. We usecross-validationto select - The

shrinkage parameter

A small positive number. This controls the rate at whichboostinglearns. Typical values are 0.01 or 0.001, and the right choice can depend on the problem.

Very small can require using a very large value of in order to achieve good performance - The

number of splits

In each tree, which controls thecomplexityof theboosted ensemble

Often works well, in which case each tree is astump, consisting of a sinple split and resulting in an additive model.

More generally is theinteraction depth, and controls the interaction order of theboosted model, since splits can involve at most variables

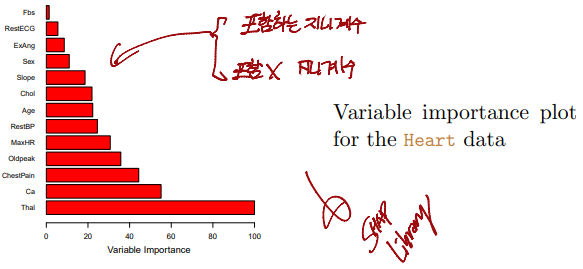

Variable importance measure

- For

bagged/RFregression trees, we record the total amount that theRSSis decreased due to splits over a givenpredictor, averaged over all trees - A large value indicates an

important predictor - Similarly, for

bagged/RFclassification trees, we add up the total amount that theGini indexisdecreasedby splits over a given predictor,averagedover all trees